For better or for worse, everybody desires for a second go at their greatest failures. Life is cruel and fleeting, and there is perhaps no greater personal misery than outright rejection, especially when it stems from something you have loved and created to share with the world. When episodes 25 and 26 of Neon Genesis Evangelion aired in Japan in March of 1996 (one month later for Americans, but still many years before online file-sharing was even remotely possible), the ensuing uproar could not be overstated. Series creator Hideaki Anno amassed an inordinate amount of hate mail, including death threats, for his conclusion, which appeared to betray the show’s premise — teenagers piloting giant mech suits called “Evangelion” (or “Eva”) to prevent the destruction of the world from equally enormous cosmic entities known as “angels” — in favor of something far more abstract and introspective. Looking back at those final two episodes now, it’s difficult not to admire them as bold, counterintuitive choices, embracing the production’s heavily-reduced budget to psychoanalyze our characters and offer series protagonist Shinji Ikari something of a happy, life-affirming ending. Nevertheless, Anno charged forward with a “proper” resolution to the story, now equipped with the financial means to fulfill his vision. The result was 1997’s Neon Genesis Evangelion: The End of Evangelion, a singularly astounding feature film that granted every fan wish, before mercilessly ripping them away all over again, allowing Anno to end the story on his own terms and deliver one of the finest artistic achievements of the 20th century.

The End of Evangelion acts as an alternate ending to episodes 25 and 26 of Neon Genesis Evangelion, slotting in their place right after episode 24. Following the death of Kaworu, the last angel, NERV headquarters (the base of operations for the Eva units) has been deemed expendable by their overseer, SEELE, in favor of expediting their plans for the Human Instrumentality Project (in broad terms, a sort of “forced evolution” of the human race that would allow them to achieve a transcendent state and obviate the need for their corporeal forms). Gendo Ikari, NERV commander and Shinji’s father, has an Instrumentality agenda on his own, looking to betray his superiors and reunite with deceased wife Yui, whose soul inhabits the very Eva his son pilots. He’s accompanied by Rei, the clone of his wife in the body of a 15-year-old girl, who will eventually act as a vessel for the destruction of mankind. These clashing motivations trigger the central conflict for the first half of The End of Evangelion, resulting in the systematic slaughter of nearly all of NERV personnel, a blunt and astonishing sequence of graphic violence. Meanwhile, Shinji has spiraled even further into a deep pit of depression, having been responsible for Kaworu’s death at his own hand, which is incidentally also where the fate of mankind will fall.

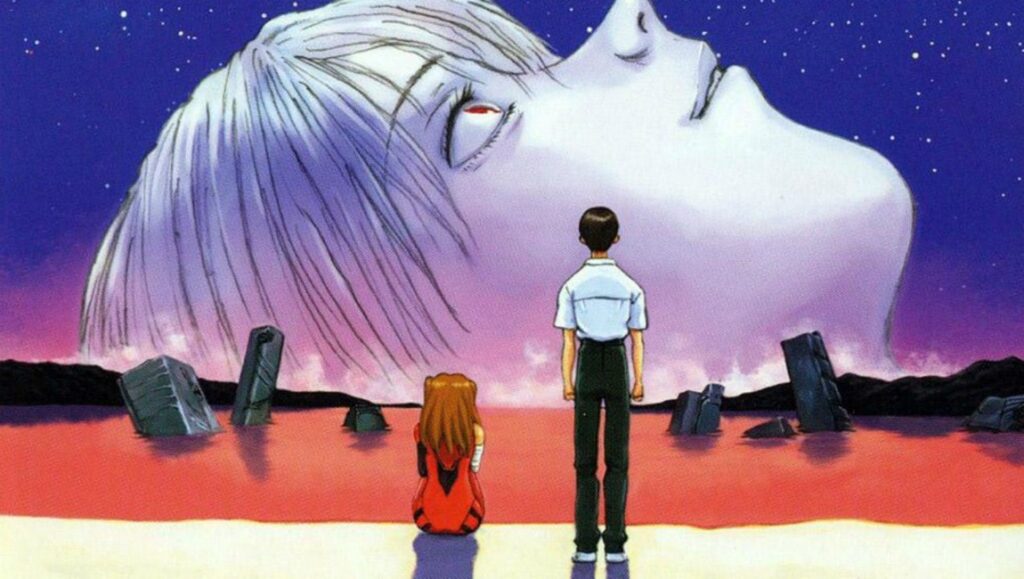

In a film positively teeming with several shocking, indelible, and just completely fucked-up images, perhaps none can surpass what hits us in the very first scene: Shinji, seeking guidance from his comatose colleague and fellow Eva pilot Asuka Langley Soryu, accidentally exposes her bare breasts under her hospital gown. The troubled teen then opts to furiously masturbate over her unconscious body, and upon witnessing the splattered ejaculate on his hand, forlornly declares “I am so fucked up” to the unseen audience. With that, Anno immediately establishes that he is no longer inhibited by the yoke of censorship, as if to say, “This is not your mommy and daddy’s Evangelion.” The rest of the feature follows suit: the aforementioned carnage at NERV expectedly unsettles, but even more grotesque is Asuka’s triumphant return to the battlefield, a thrilling and viscerally-charged sequence that gets viciously twisted on its head in the most brutal fashion. There are no small victories in The End of Evangelion, just a staggering series of cataclysmic defeats, buttoning a once beloved franchise with a pronounced air of defeat. And just when the bottom can’t seem to get any lower, Anno unleashes the Third Impact, a strikingly animated symphony of death in which all life on earth is simultaneously exterminated and returned to the primordial soup, all underscored to the dulcet and chaotically incongruous-sounding tones of the song “Komm, süsser Tod”. It’s a monumental achievement of narrative and animation, securing Anno’s legacy as one of the single greatest artists of his time.

But deep down, The End of Evangelion is not the completely nihilistic experience it’s often made out to be. For all the doom and gloom presented in the film’s 87-minute runtime, there is a glimmer of hope at the end of its darkened tunnel, as the encouraging words of Yui’s spirit indicate to Shinji that life may return to normal, should mankind wish to reclaim its human form once again. As all North American promotional art for the film states, “The fate of destruction is also the joy of rebirth,” as positive and uplifting an outlook as any. And as an appendage to Neon Genesis Evangelion, The End of Evangelion offers an arguably more profound ending under the guise of the big “action movie ending” fans may have clamored for in the first place. This would not be the last time Anno would revisit the world of Evangelion — 10 years later, he kicked off the four-part Rebuild of Evangelion saga, which produced mixed reactions but was seen as a winning addition in this critic’s eyes, particularly the final film — but nothing he has done since can top what he did in The End of Evangelion. For those who found lasting comfort in the television series’ ending, the film may not have been perceived as necessary, but we should all be grateful it exists, much like we should be grateful that we exist, for however brief a time that may be.

Comments are closed.