Cuckoo

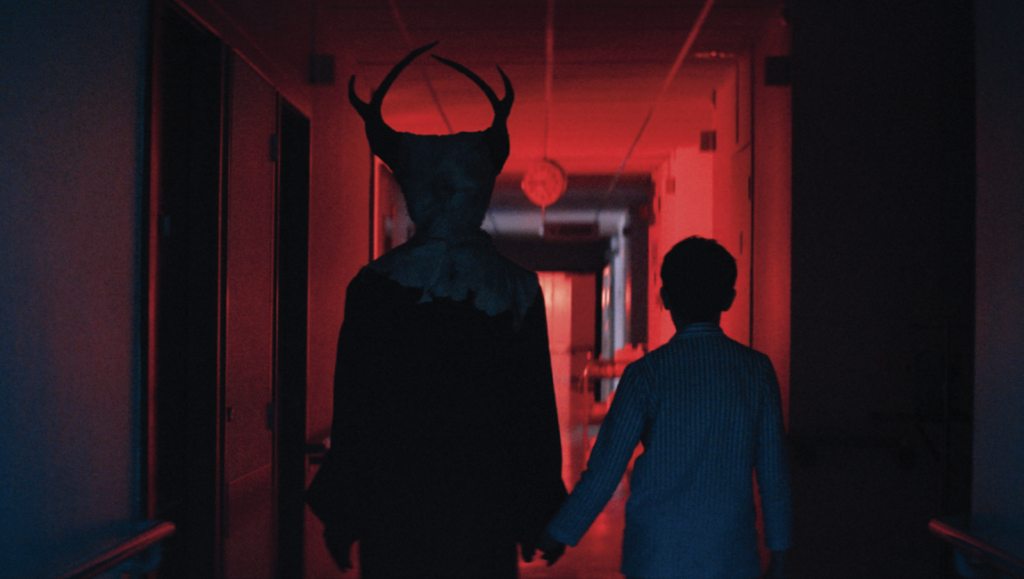

The first obvious parallel to Tilman Singer’s horror-thriller Cuckoo is The Shining. A family — Luis (Marton Csokas), the patriarch, Gretchen (Hunter Schafer), his teenage daughter, Beth (Jessica Henwick), the stepmom, and Alma (Mila Lieu), Beth’s young, mute daughter — has packed up not just from the city but from America, and is heading out to the Bavarian Alps. The adults, both architects, have been hired to design a new tourist resort for the impenetrable Herr König (Dan Stevens).

The slick and immaculately dressed German entrepreneur has the family stay at an Alpine resort, and even offers Gretchen a job at the front desk, a position she reluctantly accepts in hopes of getting together the funds that will allow her to return to the States. Her employment quickly reveals some strange goings-on, however. For one, Herr König implements strict, seemingly arbitrary rules regarding when his new employee should leave the premises. For another, the women staying at the resort have a habit of wandering around in a daze before spilling the contents of their stomachs all over the floor. Something is obviously amiss, though everyone around her seems to shrug it off for reasons that can be read as both benign and sinister.

But the weirdness doesn’t stop there: staying late one night (against Herr König’s advice/orders), Gretchen is accosted by a crazed woman dressed in a coat and sunglasses covering glowing red eyes on her way home and only narrowly escapes by finding refuge in a hospital. And as if that isn’t enough, she also appears to occasionally slip into a kind of time loop, where events play out over and over while the world around warps in a way which suggests an instability that threatens to tear apart the very fabric of reality.

Over the course of its 102 minutes, the mystery at the heart of Cuckoo slowly unravels — spoiler alert: Herr König turns out to be a bad guy — but not before pitting Schafer’s 17-year-old character against the people around her, who, predictably, don’t believe her when she tells them there are strange things happening. Gretchen is at odds with the other characters in more ways than one, though. In fact, she appears to have stepped out of a film that’s twice her age. Moody and angst-ridden, she spends her free time listening to music and plucking away at a bass guitar in true unstuck-in-time Gen-X fashion.

Of course, our main character’s issues began way before the opening reel. Like most teenagers in American cinema, Gretchen resents her father’s marriage to a woman who isn’t her mother — she even makes glib remarks about her stepsister’s inability to speak. Her biological mother passed away, and the rebellious teen desperately clings to the memory of her by listening to her mother’s voicemail greeting and pretend-conversing with her in moments of emotional distress. Singer compounds the central mystery with more emotional moments like these, but the relative ludicrousness of the plot — not a negative, to be clear — clashes with the predictable indie-drama beats scattered throughout. (The latter is a negative, however.)

The film neither sufficiently grounds itself in the emotional reality of its main character to work on a character level, nor does it seem particularly worried about playing off the audience’s fears. The dense pine woods that make up the Bavarian backdrop induce some brief twig-cracking anxiety, but Singer struggles to reconcile the genre potential of this setting with the lighter tone of the dialogue the film often veers into. And though it frequently hints at Kubrick’s 1980 horror classic, one wishes for the overt ridiculousness of something like The Red Queen Kills Seven Times (1972) — the murdering maniac makes her escape in a tiny white Beetle — or the Evil Dead films. Instead, stuck as it is somewhere between respectability, levity, and terror, Cuckoo unfortunately ends up failing to pull off any of these convincingly. — FRED BARRETT

The Soul Eater

Detective fiction has deep roots in Gothic horror — look no further than Poe’s seminal “Murders in the Rue Morgue” for confirmation. Horror has expanded on this genre interplay for centuries of literature and film, from Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles to Thomas Harris’ Hannibal novels, Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s dread-soaked Cure (1997), and beyond. Alexandre Bustillo and Julien Maury continue in this tradition with The Soul Eater, a work of procedural folk horror. The directorial duo might be most famous for Inside (2007), their exuberantly violent contribution to the New French Extremity, but over the past couple decades they have surveyed horror in various shades and permutations. From the dark fairy tale Livid (2011) to the coming-of-age slasher Among the Living (2014) and the grisly Southern Gothic Leatherface (2017), Bustillo and Maury’s oeuvre displays expansive respect for the horror genre.

The Soul Eater stays true to the pair’s career-long allegiances. Based on a 2021 novel by Alexis Laipsker, the plot follows two investigators — Commander Elizabeth Guardiano (Virginie Ledoyen) and Captain of the Gendarmerie Franck de Rolan (Paul Hamy) — who are dispatched to the French mountain village of Roquenoir to work what initially seem to be two separate cases: Guardiano is tasked with solving a married couple’s monstrous murder-suicide, while de Rolan tries to locate several missing children.

The film prowls inexorably into the shadowy halls of horror as connections between these cases unfold. Guardiano discovers that the mutilated husband and wife experienced orgasm as they died, eating chunks of each other’s flesh and stabbing each other with kitchen utensils, like something out of a Clive Barker or Poppy Z. Brite story. She and de Rolan both learn of a local legend about the soul eater: a creature that lives in the forest, luring passersby and extracting their souls before sending them home to commit atrocious crimes.

Like much of Bustillo and Maury’s work, The Soul Eater wears its influences proudly. There’s more than a little of Stephen King’s It in the notion of a village losing its children to an ancient evil force, and there’s also plenty of The Wicker Man (1973) in the concept of hapless law enforcement agents entering a small, conspiratorial community.

Where Bustillo and Maury succeed is in refusing to indulge the fashionable pretensions of “elevated horror” (a smoke-and-mirrors artifice that filmmakers usually use to disguise their own genre ignorance or narratological ineptness). The Soul Eater’s directorial duo also evades irony in all their extratextuality. Their filmography has consistently demonstrated an innate respect for horror and an unapologetic interest in the genre’s most grotesque, nihilistic possibilities. The Soul Eater is no exception.

The duo’s latest is formally lean and unfussy, offering modest flourishes in aerial drone footage and selectively deployed anamorphic lens shots. Most compelling is its folkloric engagement with the visual motif of wood: log cabins, wood-carved effigies, a sawmill suicide, and even a quiet nod to Final Destination 2’s (2003) infamous log truck opening.

But The Soul Eater is also not perfect. A key scene of emotional disclosure between the investigators falls flat, and the film sometimes struggles to balance its difficult tone. Overall, though, it’s an elegantly rendered horror procedural with a staid, subtle performance by Ledoyen at its center. Bustillo and Maury have demonstrated once again that horror contains multitudes, and it doesn’t need to play arthouse dress-up to indicate as much. Horror’s philosophical and aesthetic merits have always already been there: all one needs to do is look. — MIKE THORN

Baby Assassins Nice Days

The best action movie franchise of the 2020s is about a couple of teenage slackers who, when they aren’t being incredibly lazy, work as hired killers. The first Baby Assassins saw our heroes, Mahiro (Saori Izawa) and Chisato (Akari Takaishi), graduate high school and be forced, for tax purposes, to live together and find real jobs. The second (Baby Assassins: 2 Babies) saw them in need of jobs again, this time to pay their hitman insurance premiums and also for a gym membership they never used but still had to cough up for… — SEAN GILMAN [Read the full previously published review.]

Animalia Paradoxa

Post-apocalyptic visions in mainstream cinema usually serve a practical, introductory function, providing a digestible dose of world-building before plunging the audience into the crux of the story. Far from disconcerting the narrative or inducing a gut sense of turmoil, they establish the new order of things — for there would always be a new one if human society is concerned; the concepts of power, authority, and hierarchy remain intact, albeit in different hands. Chilean director Niles Atallah’s new experimental feature Animalia Paradoxa, on the contrary, is a baffling piece of multisensory art that makes its audience completely lose their bearings in a desolate, grim, and surreal world stricken with human destruction. Borrowing its title from a concept coined by the Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus, Atallah’s film aesthetically appropriates the qualities of “animalia paradoxa,” depicting a world that is utterly uncategorizable — as foreign and implausible as it is familiar in its barrenness, populated with the material remnants of the once ordinary lives of humans. Mixed media would be too simplistic to describe the aesthetics of assemblages that feature within: fabrics, liquids, dust, mud, rust; wooden or porcelain toys, broken and lost parts of unidentifiable objects — those are compositions of muddled, scattered media.

Similar in spirit to Tarkovsky’s “Zone” in Stalker, we only get a glimpse of Atallah’s post-apocalyptic world within the premises of a dilapidated building complex, where a figure in a gas mask, fully covered in a worn-out, spandex-like costume with mismatching colors, roams the abandoned, dingy rooms. The anthropomorphic figure’s dark gray face doesn’t give away much emotion, but they are undoubtedly in search of something related to water. They look for small trinkets among the debris and give them to a pinkish, mysterious hand with long, green nails in exchange for a jelly worm that they feed to a humanoid creature with abundant hair, hanging down in the middle of the courtyard. The figure gathers drops of water from the wet hair and attentively, patiently fills a muddied bathtub, in which they lie and dream of deep waters and sea animals. This figure who clings to the bathtub as if it’s their lifeline, seeking constant refuge within its sparse contents — are they a merman, or maybe even a mermaid? Either way, their whole being yearns for a different, better existence.

Andrea Gomez, who portrays the amphibian figure, delivers a measured yet imposing performance with a pronounced physicality — mostly moving horizontally, crawling, cartwheeling, and always on the edge, staying close to both the floor and the walls. Alongside Gomez’s character, there are other residents of the complex, whom Atallah seems to be less interested in, as they don’t go beyond being background figures in our protagonist’s path. There are several creatures in animal masks, furtively observing the outside world from the thresholds; another one who’s confined to a cocoon-like fabric and a mean-spirited preacher who recites passages from Revelation and, accompanied by her followers, terrorizes the residents.

As an audiovisual form, Animalia Paradoxa is nowhere near comparable to those active, engaging filmic texts that urge or rather (on a more moderate note) invite the viewer to ponder prescribed concepts or ideas related to the existence of nature, the human impact that ends up altering and destroying it, or the meaning of survival in a world where there’s no hope for the future. The ideas themselves are shattered, in rags, covered in dust and grime. In a manner similar to the protagonist, the viewer also has to deal with the conceptual consequences of a fictitious — or perhaps impending — apocalypse, finding their way amidst the debris of gestures, apparatuses, textures, and artistic techniques, and maybe ending up losing it.

Co-founder of Diluvio, which also produced Cristobal León & Joaquín Cociña’s surreal animation The Wolf House, Atallah has a vision that fully embraces the mindset of experimentation and the idea of film as a creative laboratory. From black-and-white analog footage of sea creatures evocative of Jean Painlevé’s work to a stop-motion puppet theater that the protagonist gets sucked into in the last act, Animalia Paradoxa is a remarkable work of dark imagination, worthy of masters like Jan Švankmajer and the Quay Brothers. However, while the latter are mostly known for work that is mostly contained within the filmic medium, there is something in Atallah’s artistic perspective that calls for exploration beyond the frame — arising from the very composition of the film, which is highly grounded in the materiality of the objects it appropriates. That is not to say that Animalia Paradoxa would work better as part of a multimedia installation or within the context of expanded cinema, but the sense of yearning and desire that overflows from the amphibian creature surely reaches the viewer and makes us want to go outside the decaying building, to maybe observe it from a different angle, or to go and find out where all those lost objects initially came from: in short, to see and hear more about this bleak world before the red velvet curtain comes down and, along with it, takes the last residues of life away. — ÖYKÜ SOFUOĞLU

From My Cold Dead Hands

It has become a somewhat common tactic for documentary filmmakers in the digital age to turn to the supercut as a way to sift through the massive amount of content and information available online on our behalf. This is the doc filmmaker as curator, exposing themselves to all of this so we don’t have to, and gathering it together in one place for us to, hopefully, find some meaning within. That meaning tends to come from the editing, whether through the arrangement of material, juxtapositions pregnant with resonance, or other techniques to add some authorial intention to what is otherwise merely a thematic collection of images and sounds.

Javier Horcajada’s From My Cold Dead Hands, running just over an hour, is the result of scouring hundreds of hours of YouTube videos about American gun culture, and it seems to want these images and sounds to speak for themselves, even if, ultimately, one gets the sense that the filmmaker has nothing but sheer contempt for his subjects. To be sure, much of what we see is funny, intentionally or not, as various Americans strut their stuff, shooting at targets or blowing shit up, or as they accidentally shoot themselves and/or fall over (or, in one case, lose their pants). I’m only human — I laughed. The overall cumulative effect, though, is not what any artist wants to hear: so what? The limitation of the approach taken here is that the only idea available to the audience is quite simple and unsatisfying, which is that it’s pretty crazy how much Americans love their guns and enjoy posting about them online, isn’t it? As a result, we are left with empty calories: a few chuckles and something of an upset stomach.

Still, the film, and particularly it being programmed at a festival like Fantasia, encourages one to think about cinema’s relationship to guns and violence, as many of us may laugh and cringe at this documentary and then go and watch countless John Wick clones in awe. We may view this documentary and think that we cannot imagine being one of them, toting insane killing machines in their backyards and training their young children how to fire them, yet at the same time we share a not-dissimilar fascination with guns and what they’re capable of in the action, horror, and crime films we love so dearly. That said, one should refuse the notion of hypocrisy this framing suggests, because it assumes the spectator’s identification with “gawking at the freaks” onscreen here. Gun culture in America is fascinating precisely because much of what animates it — government distrust, media-fueled fear-mongering, patriarchal machismo, racist ideology — are systemic issues that manifest themselves through consumerist cultural values located in the barrel of each and every gun they possess. I’m not gawking; I’m scared shitless.

If anything, the cluster of videos in Horcajada’s film emphasizes the power these symbols hold without offering any critique of how they’re manipulated or where they originate, or indeed what happens when they’re no longer symbolic. The takeaway seems to be that Americans are simply too stupid to own guns. This is not a compelling idea. Perhaps it’s unfair to expect something more from a documentary on the subject than one does from a slick action film with gun-wielding heroes and villains, but culling through endless real-life examples in an effort to comment on American gun culture ought to spur one to have something to offer beyond a sneer. — JAKE PITRE

Kryptic

Alternating between icky-squishy horror, fish-out-of-water comedy, and doppelgänger abstraction, director Kourtney Roy’s Kryptic certainly lives up to its title. If the whole thing ultimately feels a bit like a shaggy dog story, it’s so charming on a scene-by-scene basis that you might not care that it doesn’t add up to much. The film opens with Kay Hall (Chloe Pirrie) embarking on a guided tour through dense forests. Ostensibly geared toward cryptozoology enthusiasts, one gets the impression that Kay is lonely and socially awkward, and that this excursion might be an attempt to make friends. But she hangs back from the group, eats lunch alone, and otherwise seems too timid to reach out to any of the other women in the group. But she’s also there with an ulterior motive; Kay is interested in the disappearance of famed Cryptid researcher Barb Valentine. It seems Valentine vanished in this same wooded area while hunting for a Sooka, a creature that is said to be able to manipulate time and space around anyone who encounters it. Naturally, Kay almost immediately runs into it, setting off a series of increasingly odd misadventures as Jay seeks to put her life back in order.

Kay wakes up back at home with no memory of how she got there, or even who exactly she is. She wanders around her house in a daze, as if seeing for the first time. When someone calls and asks her to pick up an extra shift at work, she doesn’t know what her job is (Pirrie’s delivery of “I’m a fucking veterinarian”’ is fantastic comedic acting). Eventually, she spots a picture of Barb Valentine and realizes that they look exactly alike (or are simply the same person; it’s unclear which, or if it even matters). Soon, Kay returns to the forest to retrace her steps and figure out what happened to her/Barb. Interspersed throughout this first act are brief glimpses, presumably flashbacks, of Kay cavorting with a fleshy, sticky mass in an orgiastic delirium.

Working with writer Paul Bromley and cinematographer David Bird, Roy’s oddball film charts something of a community of eccentrics who have sprung up in and around the world of these fantastical critters. Kay’s journey retracing the steps of alter-ego Barb takes her to a deserted roadside motel, a hole-in-the-wall bar, and eventually a trailer park. Each stop leads to a strange encounter, be it with the extremely gregarious, slightly of -motel manager or an aggressively horny bartender. There’s an undercurrent of freeing oneself from repression shot through the narrative — strange sequences of Kay fucking various people feature gloopy fluids, tendrils, and gaping vaginal imagery, as if Georgia O’Keeffe were collaborating with Giger.

Kay eventually encounters Barb’s husband Morgan (Jeff Gladstone), and things shift gears into a sort of feminist parable about overcoming a controlling partner. Critics have already jumped to compare Kryotic to David Lynch or Under the Skin, the sort of grasping assertion that obfuscates more than it illuminates. Kryptic is not as confidently stylized as any of those particular works, and Roy can’t quite find a formal equivalent for the narrative’s various mysteries. In other words, even as the story veers off into various abstractions, visually it remains pretty pro forma. Brief glimpses of the Sooka and Kay’s sexual encounters aside, the camera isn’t doing anything particularly interesting (although the British Columbia forests are quite lovely). Still, if there’s ultimately a frustrating disconnect between form and content that hampers the overall experience, Pirrie’s fine performance and a welcome streak of deadpan comedy mark Kryptic as a worthwhile curiosity at worst. — DANIEL GORMAN

Oddity

Having recently acquired a rustic palatial estate in the Irish countryside, Dani (Carolyn Bracken) tends to interior renovations while husband Ted (Gwilym Lee) works at a nearby psychiatric hospital. One evening, Dani receives a knock on the door, and opens the speakeasy to reveal a man named Olin Boole (Tadhg Murphy). Frantic, unkempt, and sporting a prosthetic eye, Olin asks to be let in right away. Not one to immediately let a stranger into her new home, Dani refuses, but then receives even more distressing information: Olin has seen someone else enter the house, and asserts she is neither safe nor alone behind the locked door. If he’s let in, he will check the house for her and leave if everything’s all clear. If not, she’ll be forced to face these unfamiliar grounds on her own. It’s a real “damned if you do, damned if you don’t situation” for Dani… — JAKE TROPILA [Read the full previously published review.]

Adrianne & the Castle

In our modern world, love and cynicism often seem to dance in a delicate balance. In an age where skepticism frequently overshadows sincerity, it’s easy to question the existence of love stories that transcend either the commonplace or the schmaltzy. We are bombarded with tales of fleeting romances, broken relationships, and the harsh realities of human connections, making it hard to believe — at least according to art’s assertions — that true, enduring love still exists. Amidst this sea of doubt, stories like that of Adrianne & the Castle emerge as surprising curios. The film, which chronicles the tale of a man so deeply in love with his wife that he turned his home into a castle dedicated to her every artistic whim, challenges jaded perspectives and invites viewers to reconsider the possibility of timeless, unwavering devotion. It reminds that perhaps, even in our most cynical moments, extraordinary love can still be found.

Directed by Shannon Walsh, Adrianne & the Castle tells the story of Adrianne Blue Wakefield St. George and her husband, Alan St. George. She, a flamboyant and self-proclaimed artist, was a woman of immense presence and creativity. Their love story, spanning over three decades, is here captured through a blend of archival footage, interviews, and reenactments, revealing a couple who lived life on their own extravagant terms. The titular castle, Havencrest, located on the Mississippi River in northern Illinois, is a testament to their shared dreams and Alan’s undying fidelity to his wife, who passed away nearly 20 years ago.

Walsh’s film charts Adrianne’s vibrant personality and impact on those around her. Known for her flamboyant fashion and larger-than-life persona, Adrianne was a muse to Alan, and also to herself. The couple’s life was filled with creativity, from the narrative films Adrianne made to the elaborate parties hosted at their castle. But despite the outward glamour, the film also seeks to uncover deeper layers of their relationship, and particularly the inevitable grief that followed Adrianne’s passing. It’s not only rich emotion that marks Adrianne and the Castle, however, but Walsh’s means of conveying it: it’s hard to imagine a more moving declaration that a scene where Alan oversees a reenactment of their first conversation, nitpicking the tone and head movement of the actress portraying Adrianne, ripples of profound feeling stirring his visage.

Alan, who now preserves Adrianne’s legacy through Havencrest Castle, is portrayed as a devoted husband struggling to find meaning without his partner. The documentary explores remembrance as grief’s chief ingredient, and utilizes Adrianne’s extensive journals and home videos to paint a grand portrait of their extraordinary life together. Walsh’s innovative approach includes further reenactments of pivotal moments from the couple’s past, adding not just an element of remove as canvas for a present-day Alan to see his memories sketched upon, but also imbuing the film with a fitting measure of theatricality that mirrors Adrianne’s flair for the dramatic.

Adrianne & the Castle skillfully balances the fantastical elements of the couple’s life with the poignant reality of Alan’s loss. Perhaps predictably given the material, it does occasionally dip into the overly sentimental, but such instances are largely the product of Walsh’s willingness to respectfully let Alan guide the story, and her delicate direction makes sure that whimsy usually wins out over the maudlin. The result is that viewers are not simply told, but guided to an understanding that Alan’s building a castle was not merely an act of devotion — it was an act of preservation. Adrianne and the Castle, then, is an outright rebuff to a world rife with cynicism, and a convincing argument that there are still stories of love in the real world that defy the ordinary and embrace the extraordinary. — EMILY DUGRANRUT

Infinite Summer

In Miguel Llansó’s latest, three young women fall under the strange spell of Dr. Mindfulness, whom they meet on a virtual reality dating app and who offers up a new and exciting possibility with his own mindfulness experience. Donning a cumbersome device on their faces, they succumb to a seemingly drug-induced erotic daydream, but something seems off about it from the beginning, and this so-called Dr. Mindfulness may not be who he says he is, and what does any of this have to do with the local zoo? Soon enough, a couple of bizarre Interpol agents show up to investigate, until it all (kinda, sorta) comes together. The intrigue suggested here, though, is hardly a propulsive concern of the film itself, which proceeds with a wandering eye and a relaxed style that can chafe as often as it lulls.

Ambiguity can be a powerful cinematic tool, or a crutch. Infinite Summer leans dangerously close to the latter case, flirting with complicated ideas about identity and transformation but refusing to engage with the severity of the consequences therein. The film feels like a fantastical addendum to the classic clip of David Lynch and Harry Dean Stanton describing the self as “nothing,” there is no self, and laughing about it knowingly. Llansó’s script dabbles in the conventions of a coming-of-age tale but with a transhumanist bent, deadpan yet sincere, a tonal mishmash that strives for profundity if somewhat aimlessly. That roaming spirit is relatable enough, for any of us seeking meaning in the doldrums of modern life.

The visual effects work make up a convincing near-future augmented reality apparatus and perspective, ultimately leading to a number of transfixing sequences as the girls reach a kind of druggy transcendence. The cast is serviceable, though only Steve Vanoni as Detective Jack, one of the Interpol agents, manages to stand out. It’s easy enough to fall under the film’s overall easy charm, but it simultaneously lacks momentum and seems disinterested in actually pulling on the threads it teases. Take, for instance, the film’s interest in wellness or mindfulness as understood by app developers and/or hucksters, which is well worth satirizing, as we are inundated with pitches for easy solutions to life’s worries through a simple subscription to the latest app promising betterness for a price. The satire, though, stays at a surface level, particularly as the film seems to eventually buy into existentialist enlightenment as a way out, regardless of the technological manipulations at hand. It can leave the viewer feeling befuddled, as though the answer to the anxieties it presents is simply acceptance. After all, if there is no self, why should it matter? — JAKE PITRE

Comments are closed.