The first thing you need to understand about The Deliverance is that said deliverance is different from an exorcism — no intercessor is needed. At least, that’s what the film clumsily announces at one point, either a shrug of an effort to differentiate this from its obvious horror film forebears or an in-joke that’s tonally mishandled in execution. But make no mistake, Lee Daniels’ latest effort is a firmly post-Amityville movie in most ways that matter, conceptually and materially located at an approximate intersect of that film, the likes of Insidious and Sinister, and any number of generic “The Exorcism of…” projects. Like so many efforts of similar triangulation, The Deliverance is inspired by a true story: the 2011 Demon House case in Gary, Indiana — which, ironically, engendered a series of exorcisms, not deliverances… — wherein Latoya Ammons, her three children, and her mother were plagued by paranormal activity.

So, yeah, nothing new to find in The Deliverance’s basic framework. Of more initial intrigue, then, is Daniels’ first foray into outright horror, which feels like, if not exactly a natural progression, something of a logical pivot for the man who made the genuinely disgusting (and very bad) Precious and the woefully underrated modern camp classic of grimy, slimy pulp with The Paperboy. While it’s tough to full stop refute assertions that the filmmaker is a purveyor of poor taste, it’s also tough to deny his particular aesthetic sensibilities — are there any other directors whose pre-horror work could still be described as… gloopy? — might lend themselves nicely to the horror genre, or that the genre might help hide his worst tendencies with regard to arch dramatic development. Luridness has always been his primary stylistic quality, so why not harness that toward horror?

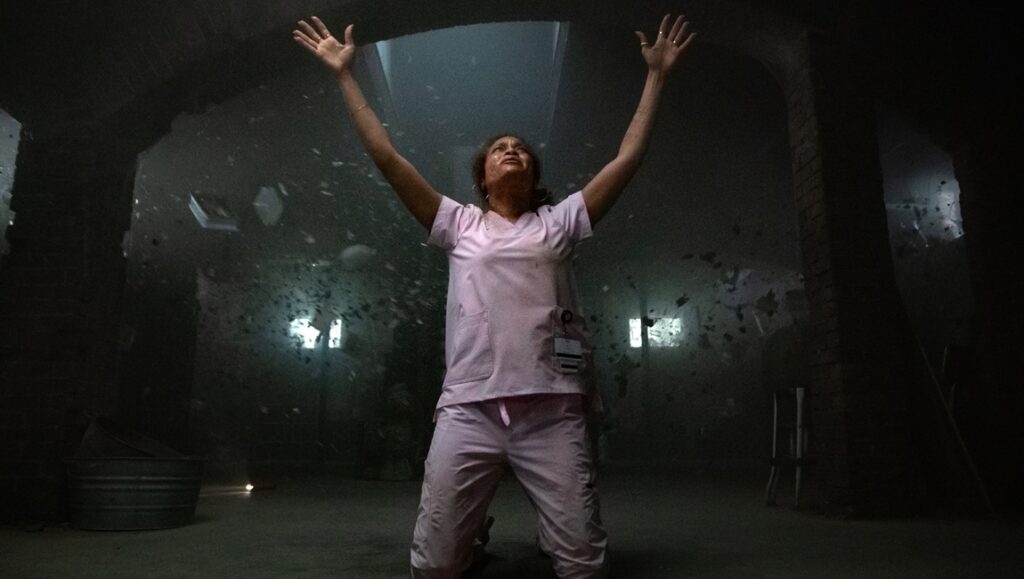

And indeed, at its best, The Deliverance is a welcome antidote to the miserable, metaphor-driven landscape of modern horror. Interestingly, Daniels still indulges the trauma-forward nature of the genre’s recency, as at its core The Deliverance is a multi-generational saga of familial abuse and the destructive cycles that are as easy to slip into as sweatpants. Andra Day (unequivocally excellent) is Ebony Jackson, an ex-con alcoholic mother struggling with sobriety, raising (and physically abusing) three kids alone while her husband is deployed overseas, and enduring regular visits from Child Protective Services. Ebony’s mother Alberta (Glenn Close, in full vamp mode) has also moved in while undergoing cancer treatment, and the two share a strained relationship, burdened by sins of the past and disrupted in the present by the latter’s vocal opinions on the former’s parenting. As these things go, bumps in the night begin soon after the fivesome moves into their new house, and before you know it, all three kids are acting strangely — in a Daniels’ film, that means dropping trow in order to sling handfuls of shit at a teacher or giddily cackling at stories of loved ones dying from AIDS.

But rather than locating in all this some allegorical boogeyman to reckon with — though that’s there too, for those who prefer such easily digestible goop — Daniels sticks to his standard garish texturing practices, ladling heaps of miserablism, melodrama, and sardoodledom on top of what’s a fairly otherwise a fairly pro forma possession narrative. In The Deliverance, the Jackson family’s domestic struggles exist concurrently to its supernatural ones rather than being one and the same, the former its own kind of horror that existed before the film’s commencement and will surely persist after. Whether one flinches at Daniels’ approach to broad characterization is another story, but there are also welcomingly intimate moments of balance here, particularly from Close as she considers the wounds she has left on her daughter.

None of this is to overstate The Deliverance’s merits — it’s ultimately a pretty mixed bag, subversive of convention in some ways, over-cranked by half in others — but rather to observe the ease with which Daniels’ baroque approach to drama translates nicely to a horror framework. It’s unfortunate, then, that the specifics of the possession subgenre prove a trickier task for the director. The returns have been diminishing for a while when it comes to small children screaming invectives like “You cunt!” in demon-deep voices, as they have been for bedeviled bodies contorting into broken shapes or crab-walking up walls. Daniels does little to tweak such iconography, content to stick to the greatest hits playbook visually and drowning his film in darkness (though also showing an inclination to punctuating these scenes with bursts of light, fire, etc.) in order to mask an overall lack of compositional flair. And then there are some failures of logic to contend with, like when the possessing entity suddenly unveils doppelgänger ability in the film’s climactic sequence. Is it ultimately worth the effort in a film like this to take umbrage with the logic of a supernatural being who would apparently prefer to make a poopy than take the shape, and thus power, of any person? No. But this gambit also isn’t leveraged toward any visually inventive ends, and instead proves to be the film’s most conspicuously overt embrace of its metaphorical bent: Ebony at war with herself. Of course, it wouldn’t be fair to suggest this undermines or wholly contradicts what worked well elsewhere in The Deliverance, but perhaps it’s as fitting an ending as there could have been. After all, anyone who has seen his films knows that Daniels the director likewise seems always to be at war with himself.

DIRECTOR: Lee Daniels; CAST: Andra Day, Glenn Close, Caleb McLaughlin, Anthony B. Jenkins; DISTRIBUTOR: Netflix; IN THEATERS: August 16; STREAMING: August 30; RUNTIME: 1 hr. 52 min.

Comments are closed.