Awaara was restored in 4K by the National Film Archive of India (NFDC) under National Film Heritage Mission, a project undertaken by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. This restoration screened at the 49th Toronto International Film Festival, marking the centenary of Raj Kapoor, often termed the “Greatest Showman of Indian Cinema.”

He looks at the bread and laughs out loud. A mannish, manic cackle leaks from the mouth of an incarcerated, cherubic street urchin in multi-hyphenate romanticist Raj Kapoor’s genre-defining, socialist crime drama Awaara. It’s in this crucial instance of masterful superimposition, captured by the stark and transcendent lens of Radhu Karmakar, that the film’s protagonist Raj (a startling Shashi Kapoor, in his early years as a child actor) blurs jarringly into a closeup of his jovial but disillusioned adult self (played by the actor-director-producer Raj Kapoor himself, in eclectic registers, with an ache both grandiose and contained). As a vagrant youth, Raj still convulses with laughter at the sight of a meager roti, the round, wholewheat flatbread, tossed his way in a crowded prison compound, its melodramaticism scored to swelling violin crescendos, distinct from the food of the impoverished in the Bressonian tableaux of Uski Roti or social realism of Do Bigha Zamin. “You know this roti, she makes you dance,” he exclaims to an angry prison guard while clothed head-to-toe in a striped uniform with a hat to match, humorously belying the cruelties of grain. After his ailing mother’s desperate plea for a mealtime morsel pushes young Raj into a life of fugitivity, there was no going back. This criminalization of the destitute, who was once born of noble parentage, preoccupies Kapoor’s Grand Prix-nominated, Dickensian, momentous, and rhapsodic Awaara.

Penned with novelistic flourish by prolific Marxist writer (frequent Kapoor collaborator of over 30 years, and ardent member of the communist Indian People’s Theatre Association) Khwaja Ahmed Abbas, along with V. P. Sathe, Awaara was 20-something, successful movie star Kapoor’s third auteurist turn, after his founding of R.K. Films alongside a searing directorial debut in Aag, followed by his scenic multi-starring romance Barsaat. But Awaara turned the tide for the triple-threat maestro in a manner unlike any other. Both critical darling and commercial sensation, this postcolonial hymn, invoking La Strada’s postwar flânerie with a Cecil B. DeMille flair, launched a thousand tropes, from familial reunification to the social stigmas of a fatherless upbringing, for Hindi-language cinema. Kapoor’s pièce de résistance narrates the part-Oedipal, part-Ramayana-esque tale of Raj, whose mother Leela (a finely maudlin, affecting Leela Chitnis, cast in a modernist, or neo-traditional, image of disowned wife and mother Sita) is banished by her self-righteous, insecure husband, Raj’s father, respected Judge Ragunath (played by Kapoor’s real-life father, formidable actor Prithviraj Kapoor) in Lucknow, on suspicions of adultery, after Leela is abducted, then released, by vengeful brigand Jagga Jasoos (an aptly histrionic and sinister K. N. Singh). Now branded an illegitimate offspring, Raj grows up an impoverished castaway in the slums of dog-eat-dog Mumbai. His fated foibles lead him, conflictingly, into both the murky trades of Jagga as well as the blossoming affections of his long-lost, cloistered childhood sweetheart, the conscientious lawyer Rita (the legendary Nargis, of Mother India acclaim and Andaz élan, in an unforgettable, scene-stealing turn as both sedate, fresh-faced paramour clad in modern saris with button-up shirt blouses, as well as the rare onscreen working woman, representing a legal vocation tied to justice), who incidentally happens to be the doted-on ward of Ragunath himself.

Heightening, in a sense, the Great Depression-set, placid parental desperation of John Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath, with a reversal of the bruising, paternal humiliations of Vittorio de Sica’s Bicycle Thieves, Kapoor’s historic grosser (earning a still-unmatched revenue of $40 million in overseas collections after its release) is a legal fable about hunger, for both bread and belonging, in a feudally unjust but newly independent India. Kapoor’s hero, Raj (endearingly called Raju), a benevolent bastard, is self-cast in the image of Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp. Often touted as the “Clark Gable of India” with a notable likeness to Ronald Colman, the actor distinguishes his persona by way of costuming, composed of loose, ankle-length trousers, a tattered bowler hat, a referentially animate moustache, and a kooky gait. In this iconography of the noble wastrel, the cineaste hails the spirit of the anguished everyman, by turns a vagabond with delightful street smarts and a pickpocket with a heart of gold — a figure who guides much of Kapoor’s filmography from the ’50s, emblemizing the progressive, Nehruvian socialism of a hopeful but harried nation.

Both socialist and spectacular, Awaara was also reportedly a favorite of Mao Zhedong, and generationally beloved by audiences in the Soviet Union, the Eastern Bloc, West Asian countries, and the Arab world, alike. One locates the unsurprising rationale for its globe-amassing appeal in the film’s searing commentary on social evils, the suffering of the poor, the injustices hurled at women, and the often dual, classist standards of the law. Thematic polarities imbue ambiguous, portentous morality, wrenchingly compounding both the inner and outer workings of Awaara. The film indicts the postcolonial viewer with sonorous urgency: is a felon born a felon? Is man a victim of his pedigree? Are the unforgivable errors of the rich ever put to trial? Is it wrong to condemn the crimes of kin? What is justice in matters of the heart, when the organ’s own beating courtroom weighs the scales between vengeance and yearning? Nargis’ Rita, an advocate on her way to be a magistrate, repeatedly follows this line of inquisition, demanding answers of her guardian and mentor Ragunath as he takes to the witness stand. “Can you explain when, how, and why you threw your wife out of your house?” Steeled, with a characteristic, thoughtful hesitation, the actress delivers an indictment of the historically revered patriarch in the annals of Indian film history.

Kapoor and Karmakar conspire to conceive a staggering visual language in the legal dramatics of Awaara. Guided by Kapoor’s adept, emotive sweep, Karmakar’s eye conjures the expressionistic set pieces of Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane, drawing in particular on Gregg Toland’s symbolic, seismic high- and low-angle shot-taking, with reverberations of Sergey Urusevsky’s severe but spellbinding facial blocking in Mikhail Kalatozov’s Soviet war romance The Cranes Are Flying. Karmakar’s resplendent but startling play, of harsh, contrasting lights and sharp, engulfing shadows, illuminate Ragunath’s hubris, tremulously dancing across the actor’s frightened, aging though still handsome, face in order to reveal in ominous flashbacks his brutal disownment of Raj’s pregnant mother one torrential night. “Good people are born to good people, and criminals are born to criminals,” the patriarch utters, stiffened by his own hypocritical resolve. His countenance, once again bearing flitting reflections of the pattering storm outside, exteriorizes lurking suspicion. “Only the son of a respectable man can be a respectable man,” he later sloganeers, cementing his casteist beliefs, with a certain dread, or paranoia, about himself.

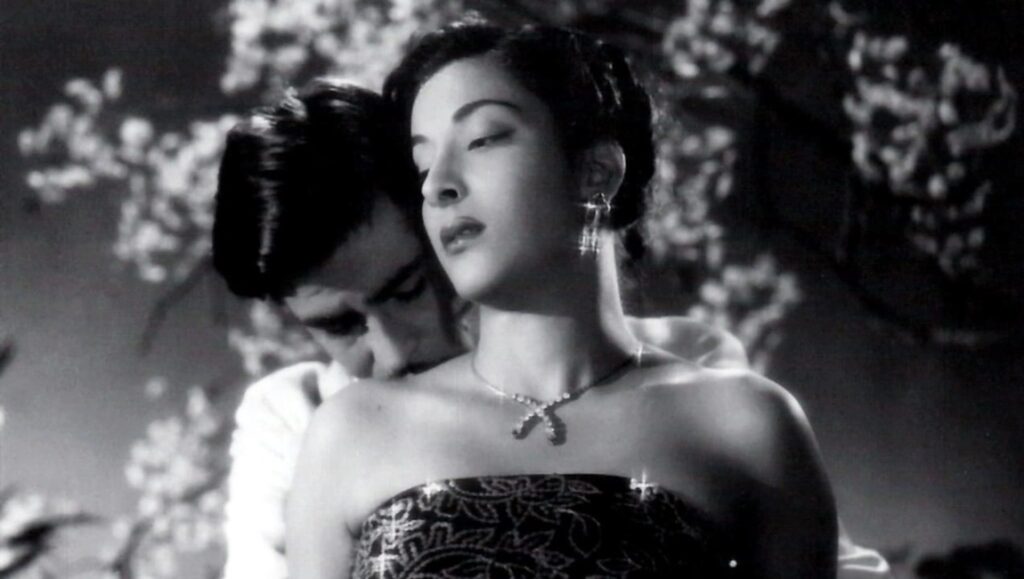

Snaking in between the taut bookends of nail-bitingly moving courtroom sequences are the choicest pleasures of Awaara — a rekindled young love, across class and status, in a young city, of a young nation, between Raj and Rita. It’s a definitive romance scored by a transfixing, orchestral original soundtrack by maestro-duo Shankar-Jaikishan, with lyrics by Kapoor’s staple and prophetic humanist Shailendra. Not without its dated conflations of abuse with devotion, in an otherwise mesmeric shoreline seduction sequence, both Raj and Rita enact the dramatic timbre of Ahmed Abbas’ pronounced dialogue to craft a singularly tactile screen coupling. “The moon is watching us,” one sings to the other, a rhetoric of moonlight rivalling the luminosity of one’s beloved. “Let the boat sink,” the other responds, their shadows from behind a mast veiling their coital luster. Blanketed in revolving, caressing shots of the water, rippling with a reflection of the milky, celestial body, Kapoor and Nargis embrace in a windswept choreography. In other memorable shots, like Raj clasping his hands around Rita’s bare clavicle and planting a kiss on her neck before adorning a stolen necklace around it, or their sorrowful embrace barricaded by the bars of a prison cell (bringing to mind Martin LaSalle and Marika Greene’s carceral, clutching squeeze in The Pickpocket), the spectator is reminded of Kapoor and Nargis’ nearly decade-long off-screen romantic relationship.

Such sensuality of song and dance punctuates, and propels, Awaara’s Freudian turns, tying the wayward to his beloved, Steinbeck’s sun to Baudelaire’s moon. With musical numbers, an unfamiliar viewer is introduced to the aural novelty of playback singing in the Hindi-language talkie. In the notable track “Ek do teen, 1, 2, 3,” for instance, cabaret dancer Cuckoo Moray twirls and shimmies in her brief part as a nightclub singer-dancer while being voiced by the singularly sultry, nasal, nocturnal tenor of singer Shamshad Begum. One also learns of the tradition of the artful lip sync in disembodied but mellifluous vocals of Lata Mangeshkar and Mukesh, the latter always being cast as Kapoor’s singing voice, distinguishing the actor from the singer, or the movie star from the invisible vocalist. In another scene, we hear the words: “Moonlight feels like fire without you.” Nargis silently delivers these desirous, pining lyrics from Shailendra on camera as Mangeshkar’s prerecorded, trebling octave sings the same. Directed by dancer Madame Simkie (protégé of renowned choreographer Uday Shankar), this nine-minute, marvelously surrealist dream sequence, entitled “Tere Bina Aag Yeh Chandni,” is a victorious feat in studio-produced, avant-garde cinédance. Following in the footsteps of the 1948 dance historical Kalpana, art director M. R. Achrekar’s set evokes both the vibrantly costumed grandiosity of An American in Paris, as well as the psychedelic, loopy circularity of Salvador Dali’s brief dream sequence in Spellbound.

The picturization here is equal parts dream and nightmare; quilting Raj’s slumber are inner worlds of ideological rifts, opposing motivations, and moral dilemmas, torn between goodness and temptation, guilt and rage, devotion and destruction, romance and revenge, the Creator and the Destroyer. In this fantastical, anomalous sequence, Raj is ensnared by the suffocating tentacles of a ravaged, skullish Hell, marked by a magnifying Jagga, who blows up into a demonic giant; intermittently, Raj is rescued by the swaying, serenading Rita, swirling and turning in a collage of classical, folk, and continental dance forms, inhabiting an idyllic, pristine Heaven, of sorts. Nargis’ Rita is costumed in the image of Selene, Graeco-Roman goddess of the moon, and flanked by classical pillars and abstractionist slopes. Atop a raised, statuesque stage, she emerges ethereal from a cloud of smoke, a deity amid a plethora of worshipping Ziegfeld belles.

That this socialist drama, not without its grime and grit, is entwined with a touch of glamour, balletic reverie, symphonic musicality, or even a strong sense of the sublime, should come as no surprise. As filmmaker Kumar Shahani wrote of the film for its 2014 re-release at Il Cinema Ritrovato, “the apprehension of beauty brings both danger and desire.” Awaara confounds the viewer with its stylish, scarred, searching conscience, its intricately structured dramatization of a social fabric in flux. “The Greatest Showman of Indian Cinema,” as Kapoor is often remembered, weaves in this pickpocket tale a beguiling rift between judiciary and justice, hereticism and heredity, geneticism and determinism, father and son. As Kapoor’s trampish flâneur announces, in song, “I’m a vagabond, I have no ties, no belonging, no citizenship.” The thief turns bardic. The vagabond is one who belongs to none, while all who live belong to him.

Comments are closed.