At age six, Francis Ford Coppola waited for a Tucker Torpedo to arrive in his driveway. His grandfather, Agostino, was among Hollywood’s first generation of futurists. Emerging from a dense field of innovation, in 1926 Agostino helped patent the Vitaphone, the sound-on-disc system that would usher out the silent film era before being itself eclipsed by Movietone’s sound-on-film approach. Agostino’s grandson would inherit this spirit of progress, but found himself drawn to the losers of history — those whose dreams could never be supported by reality. Years later, he would be asked what filmmaker from old Hollywood he most admired. With the fortune of The Godfather (1971) and the failures of his post-’70s career still just a twinkle in his eye, Coppola responded, “Would you believe Howard Hughes?”

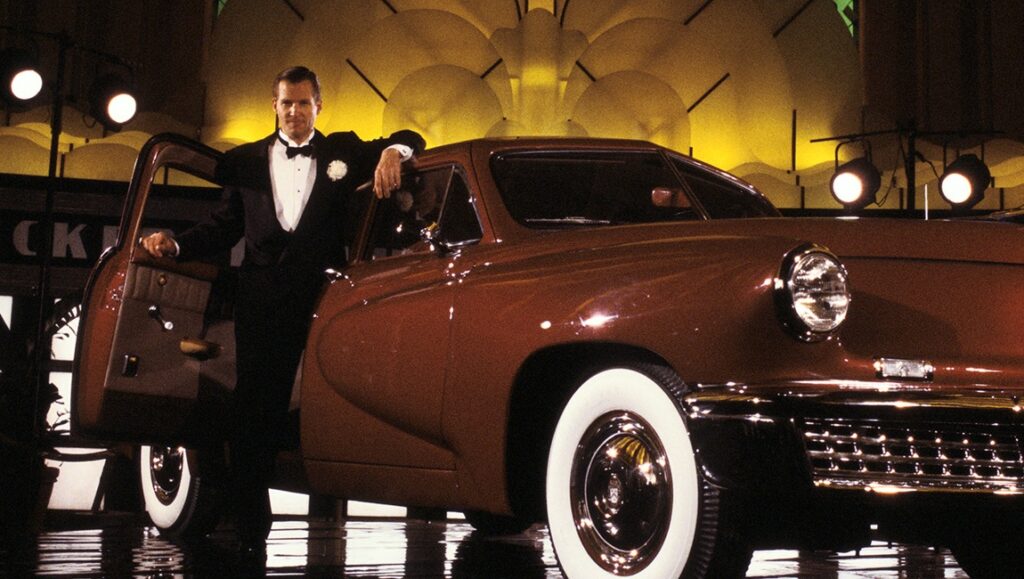

Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988) is Coppola’s lone attempt at a biopic as well as his most brazen moment of self-portraiture (at least until Twixt [2011]). He takes for his subject the story of Preston Tucker, whose “car of the future” — a clear parallel with Coppola’s recently failed Zoetrope Studios — was sued out of manufacturing before Coppola’s father could strap into a then-innovative seatbelt. “You made the car too damn good,” Tucker’s lawyer explains — the world has failed to be worthy of the inventor. Self-pity perfumes Coppola’s film, in which the saccharine air of nostalgia does battle with the cold light of the present, and failure lurks behind every moment of joy.

Alongside One From the Heart (1982), Wim Wenders’ Hammett (1982), Scott Bartlett’s experimental Interface, Martha Coolidge’s musical Sex and Violence, and Coppola’s Goethe adaptation omnibus, Elective Affinities, Tucker was on the initial slate of films to be produced totally in-house at Zoetrope Studios. Following the demise of his studio, Coppola begged the help of George Lucas, his one-time protege, to serve as executive producer. Lucas consented, but insisted that the film, once planned as an experimental musical (Leonard Bernstein even wrote a song for it), be reworked as an homage to Frank Capra. Coppola obliged, and four years after the forced sale of his studio, Tucker made it to screens.

Like the other films that emerged from the Zoetrope wreckage, Tucker is thickly stylized, tonally out of step with its era, and entirely disinterested in psychological realism. As per the subtitle, the film’s currency is dreams, and their issues of translation in a world ruled by USD (as with most of Coppola’s post-’70s films, it would be declared DOA at the box office). It tells the story of Preston Tucker’s (Jeff Bridges) bid to reshape American automaking in the image of safety, progress, and efficiency, and the efforts of the state-backed “Big Three” car manufacturers to stop him. Cries of “That’s impossible!” and “You’re crazy!” abound as Coppola shows, and Tucker learns, the lengths to which big business will go to keep a good man down.

Lucas couldn’t quite scrub the musical residue from Tucker’s final version. Tucker doesn’t so much walk as waltz through sets, the constant soundtrack’s bebopping energy eliding the time and space between his barn and factory. There’s a brittle quality to Tucker, like an over-rehearsed performance. The film seems to occur in one sustained breath. Take, for a typical scene, the instance of Tucker meeting with his design team in the family home. It opens on a swooshing pan following one of Tucker’s sons bussing a pile of dishes from dining room to kitchen. Where another film might have taken a moment to inhale, Tucker accords the boy a little sing-songy riff: “Look out, coming through, got dirty dishes, they’ll fall on you!” The film is constantly in motion, never in repose. At one point, the family moves into a Chicago home once belonging to vaudeville performers, and it seems a good fit. Tucker is ceaselessly in motion, and the stupendous height of its tightrope is evidenced by its unwillingness to take a moment to look down.

As in Capra’s populist films, Tucker finds its productive tension in the elastic pull between hysterical optimism and hysterical pessimism. Vera Tucker (Joan Allen), neglected, stalwart wife of the inventor, mocks her husband’s cheap salesman’s grin — “that crooked smile you stole from Clark Gable” — but Bridges’ performance is built from Jimmy Stewart’s winsome gabble. It’s all forward momentum, perpetually striding through sets, whipping around corners, turning nos to yeses. That a stumbling block for Tucker — and one he was pilloried for in the press — was getting his cars’ motors to reverse seems a detail nearly too good to be true.

Coppola’s obsession with what could have been was twisted in the post-Zoetrope years, from nostalgia tinged with regret to something more closely resembling real anger. On Memorial Day 1986, on location for Gardens of Stone (1987), Coppola’s eldest son Gian-Carlo was killed in a motorboat accident, leaving his father in a state of grief that would never heal, forever fixated on the immutability of time’s march forward. Infinite futures become a single past. Tucker — dedicated “To Gian-Carlo, who loved cars.” — owes its bipolar magnetism to this essential contradiction. The dreams of the past are colored by the nightmares of the present, and vice versa, not blending but whiplashing between the two: everything is forward momentum until it stops, and there’s no going backward.

A scene in which Tucker serves blue-rare roast beef at a meeting with the War Assets Commission, from whom he’s attempting to secure a repurposed aircraft manufacturing plant, while showing slides of motor vehicle crash victims, gains an unvarnished menace under this light. “The entire automobile industry,” Tucker tells the assembled brass, pitching his novel seatbelts, “is guilty of criminal negligence.” Coppola was, at the time of filming, engaged in a lawsuit with the boat’s driver (actor Griffin O’Neal) for criminal negligence. The camera holds on Bridges’ face, lit from beneath by the projector light. His smile breathes nothing but contempt.

Tucker mourns a son with a national spirit; or rather, a fantasy of pre-crony capitalism that would have been quaint even in Capra’s day. Tucker is repeatedly framed in front of Works Progress Administration paintings, and he name-drops his idols, Henry Ford and the Wright Brothers in a single breath. “We invented the free enterprise system,” Tucker tells the jury in his final courtroom vindication, “where anybody, no matter who he was, where he came from, what class he belonged to, if he came up with a better idea about anything, there was no limit to how far he could go.” One would hesitate to call the director of The Godfather II and III naïve about such matters, but Coppola’s ego shaves the boundary between himself and Tucker perilously thin.

“I grew up a generation late, I guess,” Tucker tells the jury. Maybe more than one. The film is lit through gelled windows in a perpetual sunset, creating the effect of a curdled nostalgia that seems to condense into opacity at a medium distance from the camera. Occasionally, this is broken up with sharp stabs of white light. Futures — Tucker’s, Zoetrope’s, America’s, Gian-Carlo’s — careen into the past, as the dismal present makes it difficult to recall the fantastic possibilities envisioned yesteryear. With fuel injection and six cylinders, the future plows on ahead, but who’s driving this thing, anyway?

Published as part of Francis Ford Coppola: As Big As Possible.

Comments are closed.