Why do we even watch this movie in the first place? This is one of those scary movies, isn’t it? For years we hear about it, then one day realize we’re actually allowed to watch it. So we put it on. Oh, it’s Godard. We know what to expect. He’s going to talk a lot, isn’t he? Indeed. There are going to be lots of words on the screen. Yes. And somewhere, buried beneath all the rumination, there’s a story we will barely make heads or tails of. We watch, 90 minutes, and at the end we look around, ashamed — not only did we not understand a thing he said, not only did we not understand what the movie is actually about, we didn’t even catch the very simple plot that someone is now explaining from a webpage hurriedly looked up as soon as the movie was over. We are in urgent need of help. We beg, please, can you spare a word of understanding, mister? It’s Godard. Old man Godard. Not only is it Godard, it’s Godard in two screens. And he’s so crude this time… A little girl’s face edited on top of a sex scene? What was he thinking?

Yes, this is one of those scary movies. Did you get your parents’ permission in order to watch it? One of those dirty movies. Oh, and how he talks, who the hell even knows what he’s talking about! How he indulges himself! We either come out of it utterly confused, doubting ourselves, afraid to open our mouths, or, for some reason, angry, certain of ourselves, sure that Godard had no business doing any of that in the first place. At least in Pierrot le fou there were the colors, the beach, the musical sequences. And Anna Karina! So why does he have to put us through this? It’s difficult, unpleasant. Why do we watch it then, when we see it as a chore? We watch it because we have to, because it’s an important movie, because we’ve heard so much about it, because it’s expected of us, because someone once told us, oh, you need to see this one. So we put it on, and we find 90 minutes of homework. We knew. The only problem is that no school prepared us for it.

Explanations will come later. We’ll read, we’ll return to the movie with a renewed sense of confidence, so much so that we won’t even have to watch it again. Nothing but big, important words will shoot out of our mouths: video, sex, capitalism, television. Mass media. Communism? Feminism? Experimental, of course. Bodies, family, gender, castration. The list goes on…

That’s the problem. We always must know the story. We’re always making sure we understand. And when we don’t, we shut our mouths so that nobody finds out. How does it go again? Could you remind us? First, there was the New Wave, the ‘60s, Paris in black-and-white, Cahiers du Cinéma. Rohmer, Rivette, Truffaut. Then there was May ‘68, the Dziga Vertov Group, and suddenly it’s the ‘70s. Then… then there was the ‘80s, when Godard came back, and we were given Isabelle Huppert, Nathalie Baye, Jacques Dutronc. So we go about arranging our facts. There’s no space for them all; some must suffer for the others to flourish. As always, it’s the small ones that will pay.

The fact is, the Dziga Vertov Group was already over before it could finish its last movie, Tout va bien, and this timeline leaves us in ’72, eight whole years before the next decade. So what did Godard do during the rest of the ‘70s? He was taking a rest — is that it, a rest from the holophotes? Was he tired and in need of a breather? Well, he explains this at the beginning of Numéro Deux: “I was sick for a long while, and it got me thinking about the factory…”

From ’72 to ’79, what was he doing? He was going over everything, from the top. It’s the lesson of Ici et ailleurs (1975): everything, every image and every sound, every slogan, every project, every idea — everything needed to be reconsidered, because nothing had gone the way we had imagined. The PLO soldiers he had recorded five years before now were all dead, and he hadn’t even bothered to translate what they were saying. He had gone to Pravda, to Italy, to the U.S., to Jordan and the West Bank. He had talked about all the big issues — oppression, capitalism, revolution — and now he was back and noticing he hadn’t bothered to look at the small issues at home. It took him 45 years to enter and then leave Paris, as he says in the beginning of Numéro Deux. Paris, the capital, the big letter — 45 years is already 20 more than it took Lucien de Rubempré, but at least once he finally got out, Godard actually took care to look at things around him. Very closely around him, only as far as the eye could see. And what did he see? A woman, a man, a house. The factory.

It’s easy to talk about the misogyny at the beginning of Contempt (1963) — Brigitte Bardot’s bare ass — though much more serious was the ending of Pierrot le fou, when Belmondo, betrayed, ends up blowing his head off: men and women will never be able to understand each other, so we seem to be told, much less live together. It’s only death that can save us. However, he now had Anne-Marie Miéville by his side, and she was telling him that while all that was very pretty and romantic, the fact is, we are living together now and can’t wait for death in order to fix our problems. So, if Ici et ailleurs deconstructed the romantic illusions of the bourgeois revolutionary, Numéro Deux deconstructed the romantic illusions of the bourgeois man.

All of this is to say that if Godard was making these “caustic,” “theoretical,” “pedagogical” movies, it was first of all because he himself was going back to school (as Daney put it) and trying to learn. Godardian pedagogy goes both ways: this time it really is the teacher who will learn the most. When three-quarters of the way into an episode of Six fois deux (a twelve-episode TV show the director and Miéville put on in 1976), one specifically about women, Miéville takes the microphone to say, in all words, that this is certainly his worst episode yet, that he couldn’t really work with the subject at hand, what is it that we are listening to but a teacher correcting her student? And the student, a very sage one, humbly answers: yes, you are right, I tried my best but it wasn’t enough — I’ll try again.

Numéro Deux is Godard’s remake of Breathless. Only this time, instead of ending the movie on a woman’s betrayal, that’s where the director starts it. Instead of ending on Jean Seberg’s emotionless face staring at the camera, this time he tries to understand what happens once the movie is over and we leave the theater. This time it will go this way: the husband finds out, loses his mind, rapes his wife from behind. The consequence: they later realize their five-year-old daughter had seen everything. The consequence: the woman later finds out she is now unable to shit.

Breathless? Yes. If you take away the macho posturing, the boyish ideas about women and relationships. If you take away, to put it simply, Hollywood, with its stars — Humphrey Bogart —, its gangsters, its guns, its escapism (we enter the cinema and forget our own lives; then, we go back to our own lives and expect to find a cinema in their place; that’s when fascism begins). If you take all that away, what is left? A man, a woman, a room. What else? Europe, now 15 years later; the streets (this time, no one will get shot), people, work (or the lack of it); the Capital and the province to which we return once all of our plans have failed. So, bon garçon as he is, when his producer kindly asks him to remake his first feature, his only real box office success, Godard takes it much more seriously than was expected of him; he takes it so seriously that he ends up going back to its very premise and rethinking the entire thing. He was a different man; it was a different Europe, and therefore, the movie he makes is different. Simple.

Numéro Deux: his second movie. Numéro Deux: now it’s not the man looking at the woman (in a fancy shot/reverse-shot taken from a Sam Fuller picture), but the man and the woman, side by side. Now, as so often happens, they’ve grown old, they’ve bought a house, they’ve had children. The husband every day leaves the house to go to work; the woman doesn’t, because her work is inside the house. And it’s too much, and it’s not enough. Too much: because she needs to love and work, because she needs to love at the same time as she works and work at the same time she loves. And not enough: because at the end of the day, since this work is so full of love, she feels like she hasn’t really worked (“I don’t really know how to do anything. No, I know how to produce tenderness. I know how to cook, I know how to help my son in his homework, I know how to suck a cock”). And since this love is so full of work, she feels like she hasn’t properly loved. He leaves the house and works for the benefit of his boss; she goes nowhere and works for the benefit of whom?

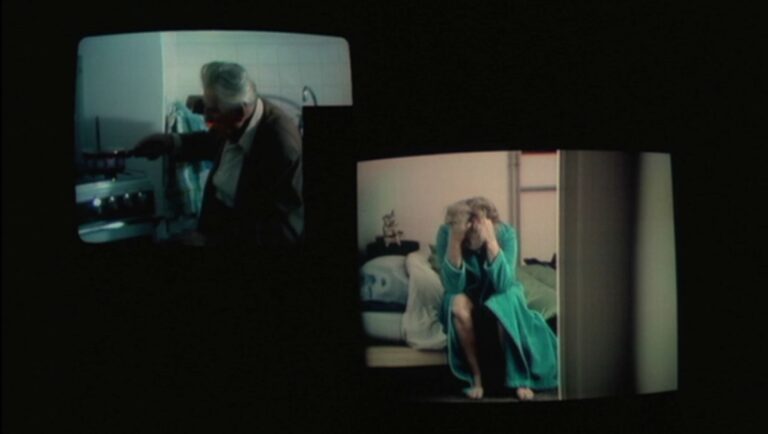

Numéro Deux: she can’t make number two. It’s all inside her. She asks her son, do you know what shitting is, and he answers, yes, I do. She answers: well, I haven’t taken a shit in two weeks. Numéro Deux: because there are two screens. Why? So we make sure we’re not falling back on the same mistakes of Breathless and Pierrot le fou: it’s man and woman, mother and child, brother and sister, grandparent and grandchild. It’s all a matter of perspective: no one has a fixed position and no one has a fixed identity. A woman is a woman? No, a woman is a man and a man is a woman. “Maybe that’s why,” says the husband, “I like when she puts a finger up my ass.”

Oh, what a bleak movie, you say. Yes, I know what you mean. What happens in the end? In the end, we’re right back where we started. No, the woman won’t be able to finally relieve herself. No solution will be found, and the movie will refuse any sort of resolution. Why? You know why. He had spent the past five, six, seven years proclaiming answers left and right, sometimes even by means of very simple equations; where had it all led him? Right back where he started. If nothing had been solved in the world, why would anything be solved in the movie? “People complain it’s too complicated. But it’s things that are complicated.” So what was Godard doing from ’72 to ’79? He was looking at things. He was trying to understand how they worked. The blind talk of a way out; me, I see. This isn’t a bleak movie, that’s too easy. Maybe it’s the world that’s bleak.

40 years later, Godard came back to this premise once more: a man and a woman inside a room. The first time he called it Breathless (individualistic: it’s the man who is breathless); the second time, since there were two, he called it Numéro Deux; lastly, he called it Adieu au langage. What had changed this time? No, the women still can’t take a shit. What had changed is this: In Numéro Deux there were children, while this time there was a dog. In Numéro Deux there were two screens, but this time there was a 3D image that separated in two. This time there were two couples, no children, and a dog. A dog? Yes. In 1975, he had contented himself with examining a situation; in 2014, he went as far as offering a solution, and this solution, it so happens, was a dog. The dog is the bridge between one and the other. So, just as the 3D images separate, then meet again at some further point, the man eventually meets the woman, through the dog.

This is no big, definitive solution, and it certainly won’t solve any of the big, insurmountable problems of the world. Godard had learned his lesson in ’75: before you talk about the other, far away, make sure you understand where you are. No, this is a small solution, that each day must be remade anew. When, around this same time, he proposed in an interview that the solution to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict would be the introduction of dogs — dogs, which Israelis and Palestinians would walk around — we don’t need to assume he was being cute, nor that he was becoming senile. Of course, he knew this wouldn’t solve anything; and besides, who was listening? He was merely communicating a discovery. Like the militant grandpa of Numéro Deux, throwing his communist pamphlets out the window of his car (“it was dangerous to be a communist at that time”) in the hope that someone at least might pick them up, take an interest in them — even though they are written in Spanish, meant for Argentinian workers, and we are still in Singapore — Godard sent his messages on the off chance that someone would pick them up from the mud where they fell and use them for something.

Comments are closed.