Henry Fonda for President

Thoughtful film curation asks us to consider films in a new light. Alexander Horwath knows this better than most, having served as director of the Vienna International Film Festival and the Austrian Film Museum during the last thirty-plus years. His Henry Fonda for President, making its US Premiere at MoMA’s Doc Fortnight, is an example, wrapped in film essay clothing, of extremely thoughtful and surprising curation. It’s a cinematic compendium about the work, life, and contradictory identity of the actor Henry Fonda; more than that, it could be summed up as a distillation of both Horwath’s cinephilic passions and his professional devotion to historical exploration.

A quote from Hannah Arendt in the film’s opening few minutes suggests that because a lived life informs the work of an actor, the work will reveal something about the lived life of the person doing the acting. Everything from enduring classics (The Grapes of Wrath, Young Mr. Lincoln, My Darling Clementine, 12 Angry Men, and Once Upon a Time in the West, among others) to lesser-known titles (The Farmer Takes a Wife, Let Us Live, The Male Animal, Strange Victory, and Spencer’s Mountain), then, act as unconscious illustrations of Fonda’s identity. The staunch Hollywood Liberal, furious at the anti-communist witch hunts that poisoned the industry in the late 1940s and early 1950s; the embodiment of the common man facing the onslaught of the Great Depression, peering out into the distance for answers he may never find; the voice of reason amidst an anxious country’s cannibalistic infighting; the unexpected bridge between the Hollywood old guard and the new, embodied by his own children. All of these versions of Fonda, and more, Horwath suggests, are found as readily in the films and characters he plays as they are in the man’s own personal history.

Horwath’s ready cinephilia makes Henry Fonda a fruitful and pleasurable watch. One marvels at the ease with which he articulates a particular Fonda performance’s qualities as much as delights in the clever and seemingly obvious connections he makes between a film and historical event. Because you can sense Horwath’s passion, his knowledge never feels overwhelming or like a suggestion of his superior intellect. Even if the film does take some time to find its rhythm, the rush of stimulation, be it Horwath’s concise narration, a sequence from his ample original footage, a clip from Fonda’s filmography, a segment of an interview, or some combination, is constant and invigorating.

If there is one idea to take as Henry Fonda’s primary argument, it is its suggestion that a lot of America’s telling of its own history takes the form of elaborate, shallow pageantry. In Horwath’s eyes it is no coincidence that the endless recycling of puffed-up myths about the conquering of the American West — shown in all its chintzy glory in contemporary Tombstone, Arizona, where the ghost of Wyatt Earp lives on more through time-warped memories of Fonda’s filmic embodiment of the outlaw-turned-lawman, than in his actual history — are as much at home in the contemporary American imagination as Ronald Reagan’s reputation as one of the country’s last great leaders. The burnt-out vestiges of truth hold far more sway when they’re reconstituted as myth; John Ford recognized this when he killed Henry Fonda’s obstinate Colonel Thursday in Fort Apache only to have John Wayne’s Captain York valorize his misguided leadership to the press in the film’s close. Horwath inverts this mythologization in Henry Fonda’s framing scenes, a 1976 episode of the sitcom, Maude, in which Beatrice Arthur’s title character formally organizes the Henry Fonda for President campaign, only for the real Henry Fonda to show up, accompanied by the studio audiences’ reverent applause, and dash her hopes. If Ronald Reagan is the worst kind of mythologized political figure because his desire was too transparent and all-the-more craven for his feigned humility, then Henry Fonda, the self-doubting, quick to anger, unbeholden Common Man, is the best kind. Our only loss is that means we’ll never get it. — CHRIS CASSINGHAM

Sleep #2

“…one very much gets the sense that Jude is interested in so many different things, both politically and aesthetically, that he’s perfectly willing to churn out smaller-scaled, experimental efforts in between his more traditional, narrative-driven projects…while Sleep #2 is a simple, even minor film, a sketch of an idea really, it’s one loaded with suggestion, potential significance, and room for intellectual play thanks to the long shadow cast by Warhol’s art ad legacy. [Previously Published Full Review.] — DANIEL GORMAN

Middletown

With an education system as corrupt and ineffectual as that of the United States, stories of real teachers making a genuine difference are few and far between. For every educator who’s made a positive impact on students’ lives, there seems to be a dozen who only entered the profession because they loved Harry Potter or wanted to be their town’s next storied football coach. It’s rare that a teacher — especially today, given the systemic constraints around what they’re actually allowed to teach and the recent rise of pre-fascism with regard to book-banning — who meets students on their level and inspires them to think beyond their current worldview and experience. In Middletown, directors Amanda McBaine and Jesse Moss (Boys State, Girls State) shine a spotlight on the rare, electrifying presence of Fred Isseks. As one student recalls, Isseks “never felt like a teacher, in the best way possible. He talked to every student as if they were an equal.” Imagine that.

Middletown unfolds as a documentary centered on Isseks’ “Electronic English” class in the early 1990s, which encouraged students to film and investigate real-world issues rather than passively absorb information (a skill society writ large would have benefited from developing before the advent of social media): “Be creative, use your talent. Use it to make stuff instead of consuming stuff.” Under Isseks’ direction, students at Middletown High School began investigating the local landfill, uncovering toxic waste, corporate negligence, government complacency, and organized crime involvement.

McBaine and Moss structure the film in traditional documentary fashion: a combination of extensive archival footage (all meticulously preserved on the original VHS by Isseks) and present-day interviews with Isseks and four of his students, reflecting on the scope of what they revealed. While this construction plays things pretty safe with regard to form, it does draw compelling parallels between the problems of that era and today’s challenges. Comparing the almost level-headed and somewhat well-spoken local politicians — the kind who could have only existed in a pre-Internet age — to the palm-greased buffoons whose presence in public office grows exponentially every year is both laughable and utterly depressing, and while the film never explicitly touches on that subject matter, it’s impossible to view Middletown in a vacuum. Blanket eliminations of environmental protections, non-existent journalistic ethics, and strongmen who throw tantrums because someone “didn’t say thank you” have left many of us justifiably cynical, if not outright hopeless.

One of Middletown’s greatest strengths lies in its meticulous documentation of what was, for the students, a genuine investigative triumph. Armed with bulky camcorders and a healthy dose of skepticism, they didn’t just report on the problem, but confronted it head-on, even going so far as to trespass on private property to capture footage of dumped medicine vials and leaking barrels of toxic sludge. Much like the inclination demonstrated by an embarrassingly large swath of Americans to trust billionaires to improve their economic circumstances, this narrative thread represents one of the United States’ most enduringly naïve notions — that doing the right thing is all it takes to get a positive outcome. Yet therein lies the film’s central tension: while Middletown might initially aim for a “hearts and minds” appeal, it mostly underscores how bleak our current situation remains. Issues of environmental degradation, corporate malfeasance, and political corruption have reached all-time levels of evil. As Rachel Raimist, one of Isseks’ former students shares, she left Middletown and ended up buying a house within a few miles of a landfill with similar problems, decades later.

But perhaps McBaine and Moss’s goal isn’t simply to uplift viewers in the face of pervasive dysfunction or convince them of the lie of American democracy and the power of the people . Instead, they remind us that personal stories can offer us all a lifeline when the larger system seems beyond repair. Even if the work of these teenagers didn’t result in a triumphant fix to environmental abuses or the cesspool of American politics, it shows how a teacher like Isseks and his students managed to spark tangible action at least once, on a local scale, however fleeting the victory was. Their experiences become a kind of testament: sometimes it’s not hope for sweeping change that keeps us going, but the human narrative of ordinary people trying that helps get us through when there seems to be no hope. — EMILY DUGRANRUT

An Unfinished Film

“Although An Unfinished Film is a convincing fiction packaged as a non-fiction, it has plenty of allusions to the real. In 2009, Lou Ye released Spring Fever, a queer romance also starring Qin Hao. The film was a radical creation not only because it spotlit homoerotic desire — which was hitherto taboo in China — but also since it was produced during Lou Ye’s official banishment from cinema, as imposed by China’s State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television. With this interweaving of real and unreal, past and present, there’s a sense of time out of joint in An Unfinished Film: as if it were gestated in an alternate timeline where Spring Fever never manifested.” [Previously Published Full Review.] — VICKY HUANG

The Triptych of Mondongo

At one end, a nearly perfunctory art documentary; on the other, a lively essay film on color; in between, a shambolic chronicle of a failed project and a personal falling out. These are the three component films of Mariano Llinás’ The Triptych of Mondongo, making its North American debut at MoMA’s Doc Fortnight. Since drawing international attention for his six-chapter, 14-hour epic La Flor in 2018, Llinás has directed several documentaries that have been nearly impossible to see in the United States. It’s apt, then, that this is the first of his projects to surface, given its similarity to La Flor. Though The Triptych of Mondongo’s three parts come in at a little under five hours, its similarities to La Flor go beyond simple structure. Where that previous film was made in collaboration with Piel de Lava, a collective of four actresses who star in the majority of the film, The Triptych of Mondongo began as a commission by ArtHaus Central to document the Mondongo Collective’s Baptisterio de Colores. And like Piel de Lava, the two artists currently comprising Mondongo, Juliana Laffitte and Manuel Mendanha, are old friends of Llinás’. (For his second feature, Extraordinary Stories, the artists created portraits of the three leads, including Llinás and cinematographer Agustín Mendilaharzu, for the poster.)

Part 1, The Tightrope Walker constitutes Llinás’ attempt to fulfill the commission, cutting between the construction of the Baptisterio, a cathedral full of multicolored plasticine inspired by Johannes Itten’s book on color theory, Kunst der Farbe, (which eventually lends its title to the third part of the triptych,) and an interview of Mondongo conducted by Gabriela Siracusano, an art historian specializing in materials. To the extent Llinás has a handle on what this first part is, it’s a focus on material, and we see a large crew coloring and shaping plasticine, painstakingly labelling the hundreds of blocks and eventually placing them in the cathedral. Focus, however, is what is lacking from this first film, in which Llinás often points the camera at his computer screen, scrolling through the film’s transcript (or is it a script?) in Word or playing Bernard Herrmann’s Vertigo score, which is spattered across the film, courtesy of YouTube. As the film closes, the computer screen pulls focus entirely, with Microsoft Word becoming Llinás voice as he types out his frustration with the materiality of the artworld in which Mondongo works. “The rich have their channels / in the bedrooms of the poor,” Llinás quotes Leonard Cohen, rendering his diversion of blame from Mondongo onto the system more insulting than absolving.

Llinás’ computer screen, rendered comically filthy by digital cinematography, is somehow an even greater presence in Part 2, Portrait of Mondongo, which begins by stating the end of Llinás’ friendship with Laffitte and Mendanha. After further outlining their differing economic stances — Llinás has come to believe that during years of his venting about the role of money in art, the two were not commiserating but making fun of him behind his back — his attempt at portraiture begins. Here, his playful, intertextual approach begins to emerge. Continuing to punctuate with the music of Herrmann, as well as Glen Gould, Llinás considers portraiture through the work of Manet, through Mondongo’s own portrait of himself, and through the reactions various men have to being filmed in a public square. This approach grinds to a halt when he proposes to Mondongo that the film become a challenge: alongside his portrait of their art inspired by Itten’s book, he will complete his own film inspired by the same source material. When he ambushes the two artists with a script in which he explains this conceit to them, he’s waylaid when Mendilaharzu reminds him of a Letterboxd review of his previous documentary, Clorindo Testa, which accuses him of repeating himself. Indeed, this sort of conceit appears in La Flor as well, the self-reflexive fourth chapter of which casts Piel de Lava as brujas, witches, in conflict with a filmmaker making an extremely long film with them who finds himself more interested in filming trees. Though Llinás insists to Mendilaharzu that “we can’t make films for a guy saying stuff on Letterboxd,” he includes an extended sequence in which he turns the review into a poem. Indeed, he seems to indulge the reviewer somewhat substantially, with the shots of him typing at his computer replacing the voiceover that is apparently at both its most prominent and its most banal in Clorindo Testa.

The whole project reaches its climax with an extended shot of Llinás face during the same conversation. Here, what is at issue is not economics or self-reflexivity, but basic courtesy. When Llinás interrupts Laffitte to point out a dog chewing on a piece of wood, she snaps. It’s this disagreement, which brings Llinás to tears, which actually seems to poison the relationship. The fight filters into the final film of the triptych, in which Llinás takes on the role of a “Fritz Lang villain,” or Lang himself, making his attempt at drawing inspiration from the Itten book. Though largely occupied with color, giving up the Herrmann music for audio taken from a concert at ArtHaus inspired by color and featuring frequent input from his color correctionist, he also casts La Flor’s Pilar Gamboa as Laffitte to reenact the argument Laffitte herself had no interest in reenacting. When they reach the previous film’s climax, Gamboa immediately takes Laffitte’s side. Llinás still fails to see the point of view, making clear why the project became untenable. That an untenable project became three films is deeply characteristic for Llinás, and his collage approach allows what is salvageable to shine. It’s a relief that his bombastic presence, and eventually voiceover, return to Kunst der Farbe, and even as he bickers with Gamboa and Maria Villar, who helps him to read Itten’s German, there’s a warmth present that is absent for much of the triptych’s second part. Ultimately, the three films are an escalation, perhaps even an apex, of the self-reflexive methods of combative collaboration Llinás has been engaging in for years. Whether it’s this escalation, the shift from autofiction to documentary, or the specific combination of personalities at play that brings the combat out of the realm of playfulness is unclear. As is whether Llinás has taken any lessons from this, with each film including a Marvel-esque post-credits stinger, the third of which seems to puckishly hint at more of the same. — JESSE CATHERINE WEBBER

John Lilly and the Earth Coincidence Control Office

“Stephens and Almereyda might not seem the most obvious pairing. The former’s films are derived from the archive and often experimental in nature, or at least interested in muddying our understanding of the divide between fiction and nonfiction; the latter’s have, in recent years, dressed a fascination with experimentation, speculation, and singular male figures in the garb of conventional narrative filmmaking. The two’s convergence on John Lilly is a happy one, resulting in a documentary that, without demolishing the conventions of nonfiction storytelling, injects much-needed life into public figure profiling.” [Previously Published Full Review.] — CHRIS CASSINGHAM

La Quinta del Sordo

Few works of art have a history as rousing or enigmatic as Francisco Goya’s Black Paintings. The tale goes something like this: Goya, possibly very ill, bought an estate outside Madrid called the Quinta del Sordo (”villa of the deaf one”), named after a previous deaf tenant. Here, in a state of near madness and possibly going deaf himself, he painted his darkest (in both shade and content) works on the walls of the villa itself. He never named the paintings, and never intended them to be seen, yet several of these murals are among his most famous and lauded today. Perhaps the landscapes of Fight with Cudgels and the two Pilgrimages existed as murals in the villa before Goya’s arrival, and the addition of his cynical processions was merely Goya’s opprobrium on the banal works he saw every day. Perhaps Goya did not paint any of them at all.

The story has all the elements of art history catnip: the early l’art pour l’art of his unwillingness and inability to exhibit these works, the unknowable nature of his intentions, and a doubling down on the trope of the mad and brooding artist giving one last rebuke to the world that made him suffer. Multi-disciplinary artist Philippe Parreno has mostly divorced this half-dubious story from the works themselves in his La Quinta del Sordo, a video work that purports to simply show the paintings themselves in great detail. Of course, as the title itself hints, the story still seeps its way in.

Though the Black Paintings have been displayed in the Museo Nacional del Prado since the late 19th century, Parreno’s film appears to portray them as if they still don the walls of his quinta, demolished in 1909. Each shot is a close-up of faces and figures isolated from their context, and only a few times does the camera ever pull back to reveal an entire work. The grim mocking faces of one painting are suddenly cut to match the suffering of the face of another: perhaps it’s from the same painting, or perhaps it’s the painting across the room. To view each work in isolation is to deny the effect of seeing these figures adorning different parts of the room and thus to deny their neighborly visits with each other or their secret conversations. Parreno partially fixes this through his disorienting presentation, though his camera and his cuts allow the viewer only his narrative.

But even more trickery is afoot: these close-ups and pans across the paintings are presented without narration and are complemented only by a minimal soundtrack and effects from the imaginary villa itself. Several slow-motion sequences of flickering sparks break up the hypnosis of viewing the paintings for too long and provide the origin story of the film’s single light source — the small orange glow illuminating only fractions of the wall at any time. These crackling embers echo throughout the empty estate until they cease, and a soft blue morning light visits the wall instead. A rain starts, and the demons on the wall become subdued. Sometimes, even a prism breaks the light into soft, small rays of hope and color; perhaps this is Parreno’s counter-commentary to Goya’s cynicism. Though neither the sound nor light were created naturally, the illusion of Quinta del Sordo’s return is a marvel itself.

And yet, this is no mere exercise in historical recreation. Parreno actively reworks the paintings by changing the camera’s focal length at a close distance. Suddenly, a crowd of faces can disappear into a blur to reveal the goat-priest of the Witches’ Sabbath, or Saturn’s maw can dissolve into abstraction as a closer look reveals only glimmers of gold light shimmering off even this black paint. The one quality uniting all of the Black Paintings is a crude simplicity bordering on abstraction: many of the faces in his crowds have no eyes or mouths but instead simple stokes of shadow, forming a rough sense of pareidolia. By shifting the focal length to allow the light and paint textures to replace features, Parreno continues this process of abstraction through time. He holds one figure in this black halo only to reveal it as a surprise or joke or jump-scare. Goya’s isolated world of darkness has become cinematic. — ZACH LEWIS

Collective Monologue

“The metaphor is blunt, but no less effective for its obviousness. Rinland’s films are typically narrated in such a way as to “educate” the viewer — here, the purpose of the given exposition feels more evocative. Where much of her previous work elucidates specific phenomena that exists within the dichotomy between man and nature, Collective Monologue lingers on a more intimate and unassuming look into the tangled web of contradictions that make up the relationship between humanity and the world it inhabits.” [Previously Published Full Review.] — JOSHUA PEINADO

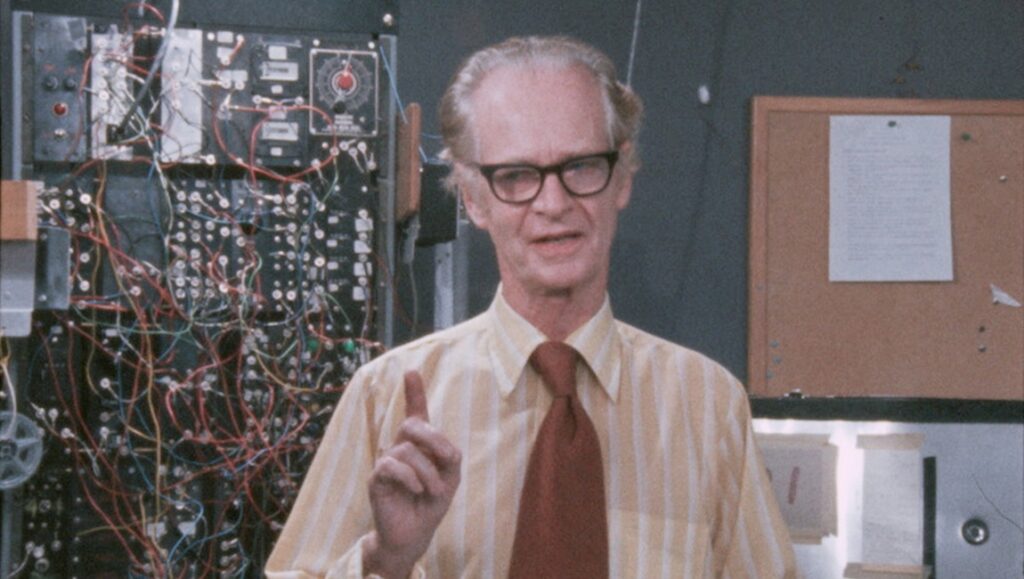

B.F. Skinner Plays Himself

A simple sprinkling of chemicals into an in-ground pool reveals more about the enigmatic figure at the center of Ted Kennedy’s B.F. Skinner Plays Himself than anything in the film’s previous 54 minutes. The images are from an abandoned documentary profile of renowned behavioral psychologist B.F. Skinner, filmed, according to correspondence between himself and the documentarian, Philip R. Blake, sometime between 1974 and 1976. The moment is significant only because it shouldn’t exist, at least according to instructions Skinner laid out in that same correspondence. For instance, he would allow scenes of him with his grandchildren and with a group of students. He would also permit scenes of him in his garden, “although there will be no scenes involving the swimming pool.” This audiovisual incongruity partly explains why the project was abandoned; but the footage exists anyways, we see it for ourselves, reassembled in Kennedy’s film as not only a document of an evolving scientific practice, but of a man grappling with the dwindling belief in the utopian potential of his own theories.

Skinner’s early experiments with pigeons tried to induce specific behaviors, such as turning in a circle, by rewarding incremental movements in the desired direction. What utopian society is there to be found here? The Second World War forced Skinner to extend this experimental premise; instead of turning in circles, now the pigeons identified missile targets on screens in the noses of airplanes. After the war he turned his attention away from birds and towards humans, hoping to improve education by experimenting with a similar, rewards-based method of instruction. What are the societal implications if human beings behave not according to their own conscience but, as Skinner argued, to external forces? Will we belong to a society so perfect that the word “rebellion” no longer has a place in our lexicon, or will we just be pigeons, fat on treats, turning in endless circles?

If anything, time has at least ensured that today’s pigeons aren’t just regular, everyday people, subject to the whims of a ruling class, though many of them are. Skinner would argue this isn’t our fault, nor that the problem, actually, is that we’re being controlled at all. The situation we must face is not that any one person, be it Richard Nixon, whom Skinner hated; or any contemporary equivalent that is, let’s say, financially backing, militarily enforcing, and diplomatically sanctioning a genocide in Gaza, is an inherently evil character. The real crisis we face, and perhaps ultimately may never conquer, is a society that reinforces those behaviors.

Which brings us back to the swimming pool. The first question has to be: why did Skinner allow it? Perhaps he wasn’t aware of his being filmed in the moment; there is no direct sound from the image, just audio from a separate, behind-the-scenes conversation between Skinner and the documentarian. Or, maybe he was promised that it wouldn’t be included in the final film, a film we know never came to be, which suggests that the footage was in some final version presented to him later on. There is no easy answer to any of these questions. Skinner’s final correspondence to Blake outlines moments in the film he disagrees with, primarily over how he is characterized, but never once mentions the swimming pool footage. Maybe the promise of more time in the public consciousness was stronger than his will. He was, after all, a deft public figure, able to harness television as a bully pulpit even, or perhaps especially, as his reputation wavered on the brink of controversy. Kennedy’s film offers no answers, just space for speculation, a fact that ultimately characterizes Skinner, too. Once the proponent of behavioral psychology’s utopian promises, by the end of the film we see a man deeply uncertain about its ability to solve our problems. It’s a testament to Kennedy’s erudite summary of Skinner’s research that a film as informationally dense as this concludes with such profoundly clarifying skepticism. — CHRIS CASSINGHAM

Eight Postcards from Utopia

“Radu and Ferencz-Flatz have created a picture-book of ephemera; if they imply the function and feedback-loop inherent in the advert-form, they also document a period of visual culture, and the dream of a Romanian utopia, as dreamt by the least utopic of people. This is a visceral history; and one imagines for Romanians, an embodiment of long-forgotten daydreams, stored somewhere in the darker caverns of the brain. There, with the Botticelli and the Assumption, a dream of the world. A dream built of the world as it was made: a dream in which we see both the place that made it, and what that place imagined it could be. Empty — and transfixing.” [Previously Published Full Review.] — MILO GARNER

Debut, or, Objects of the Field of Debris as Currently Catalogued

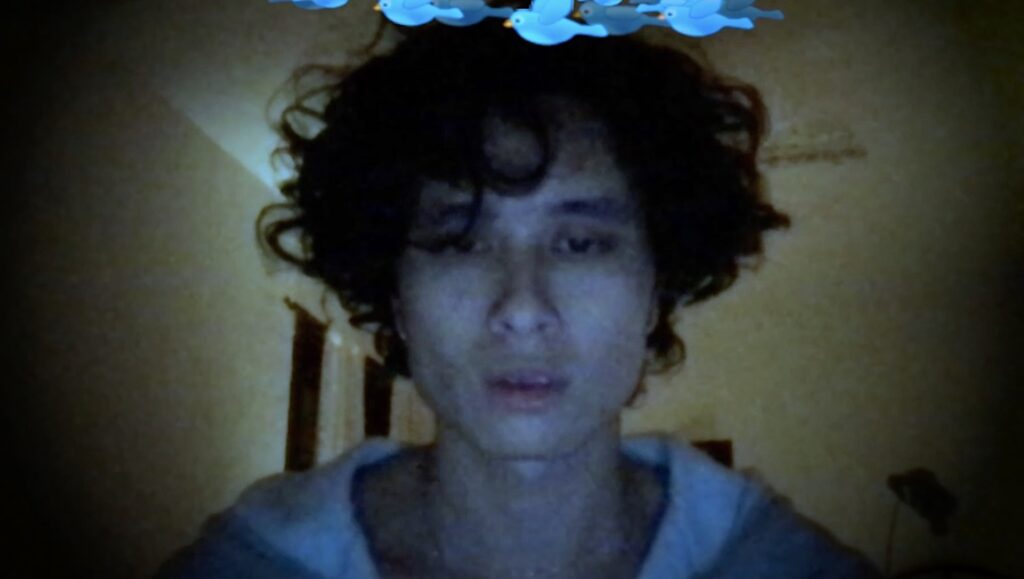

Julian Castronovo is 27 years old. He’s 6’1” and 155 pounds. This is the only biographical information you’ll find about him on his website, and it’s the same way he’s introduced to the audience in his debut feature, titled: Debut, or, Objects of the Field of Debris as Currently Catalogued. Castronovo describes it as an “inverse auto-fiction” — forging a mystery that has consumed his life. The detective story begins after a day of heavy drinking, when he finds a letter delivered to his apartment addressed to a previous tenant, Fawn. He discovers several other objects hidden in the walls by this enigma, prompting his investigation. “Who lived here?” Fawn was an art forger. Or, at least, that’s what Castronovo initially suspects. More importantly, she’s been missing for 20 years. At a certain point, Castronovo decides to turn the investigation into a film, and partners with a producer, eventually flying to Prague to get the story made, only to himself go missing.

But that Castronovo is not the one telling this story. The film is made up of screen recordings, miniature recreations, and digital artifacts left behind by Castronovo — narrated by another enigma, one who wants to investigate Catronovo’s own story. A detective story in a detective story, a film within a film. There are many threads to be followed, all intersecting with each other at various narrative and thematic ends, marks of a well-measured product. The conceit of a removed narrator adds a layer of coldness to the work that might have been better served by more time with Castronovo. He’s clearly funny, though this only comes out in small moments that “facilitate” the narrator’s investigation of his own. In some moments, the character he plays feels made in the mold of Connor O’Malley’s “lost” young men — posing himself as a failing party clown, wearing suits he gets from catering gigs around town to pretend to be a noir detective, pretending to be an employee at A24 and MUBI. Indeed, the work has a very Gen Z quality to it — not only in its being communicated primarily through webcams and digital archival material, but through objects of significance to the generation, like video filters and vapes.

Debut’s documentary aspect is fascinating as a portrait of an artist at work, and though where fiction meets reality isn’t always clear, it’s obvious that Castronovo has manufactured a lot in service to the film. Of course, as the film says, “he is who he is,” and to that end he is who he pretends to be and his life is what he created, at least for a small portion. In this all sounds a bit on the nose, there’s no denying that autofiction seems to have become an increasingly popular trend with many young writers and filmmakers these days (My First Film, anyone?). But Castronovo does enough to separate his work from the genre that it manages to feel like something resembling a breath of fresh air, and a pleasant surprise in a subgenre increasingly saturating the young filmmaker landscape. — JOSHUA PEINADO

Bogancloch

“More so than perhaps any artist outside the Harvard Sensory Ethnography Lab, Ben Rivers exemplifies this experimental approach to nonfiction filmmaking. His films have consistently taken some social or geographical fact (a landscape, a workplace, a person, an animal) and built outward from there. Rivers’ films insist that we cannot ever really understand something outside of a context. But he also makes sure that the context does not provide some prefabricated interpretation of the object under consideration. Rather, the subject and its context are mutually defining, like a figure in a landscape. He does not deal in concepts. He provokes mysteries.” [Previously Published Full Review.] — MICHAEL SICINSKI

Comments are closed.