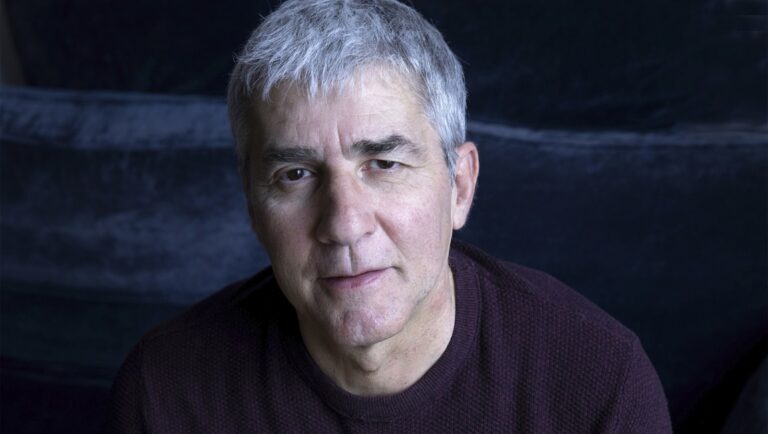

Since the release of his first short film, Heroes Never Die, 35 years ago, Alain Guiraudie has gradually built a reputation as one of world cinema’s most interesting, idiosyncratic talents. In 2001, he released two medium-length films, Sunshine for the Poor and That Old Dream That Moves, the latter of which earned the praise of Jean-Luc Godard when it screened at the Cannes Film Festival; his first long-form feature, No Rest for the Brave, followed in 2003. It wasn’t until 2013’s Stranger by the Lake, however, that the director enjoyed widespread international acclaim, and said acclaim has only grown in the time since, as critics and cinephiles have sought out and savored his works both old and new.

Guiraudie’s films often tackle similar subjects — sexual and romantic fluidity, the social and emotional impact of crime, and the inexplicable yet irrepressible power of desire — and often in similar settings, particularly the rural south of France. And yet he’s never one to repeat himself, with films that not only differ considerably from one another in style, tone, and genre, but ones which also frequently defy the expectations they establish for themselves, changing in shape, style, and form, consistently providing the viewer with a most distinctive experience.

Guiraudie’s latest, Misericordia, finds the director once again exploring those similar subjects in a similar setting, and once again defying expectations. Jérémie, a young man at a crossroads in his life, returns from Toulouse to his rural home village due to the death of the man who was once his mentor in the bakery business. Reuniting with old acquaintances, his arrival in the village ignites unexpected and unpredictable emotional responses, both in said acquaintances and in Jérémie himself. Love, sex, lies, and more death swiftly ensue as a man adrift reckons with lust, loneliness, and guilt in one of film’s smartest and most surprising tragicomedies in many years.

It’s a terrific film, as satisfying as it is unique, so it was with immense pleasure that I was able to connect with Alain Guiraudie via Zoom to discuss it in detail. Special thanks go to our translator for the interview, Nicholas Elliot.

Padaí Ó Maolchalann: I watched the movie again yesterday — I saw it back in October last year. I loved it as much the second time as the first time, so thank you for the movie.

Alain Guiraudie: You’re welcome.

PÓM: So you shot this movie in Aveyron, which is where you’re from, and it’s set almost exclusively in this one village and the surrounding areas. I wondered to what extent do your settings or your shooting locations inform your stories, or are the shooting locations and settings selected for their suitability for the story you want to tell?

AG: Well, I grew up in a village very similar to the one in the film, but it wouldn’t have been in very good taste to shoot this kind of story in the village where I was born. So I chose another village, which is about 100 kilometers from where I was born. And I chose this one because it really looks like a fairy tale village, you know, between several hills with the forest nearby, these houses around the church — it’s really the kind of village you would find in a fairy tale.

PÓM: With that in mind, I read a quote from an interview you gave previously for Staying Vertical. You said, “I think my dream film would be to make the dream actually real in a movie, or at least to create a kind of hallucinatory reality.” I found that there was something almost dreamlike about Misericordia, or maybe even purgatorial rather than dreamlike. Jérémie keeps visiting the same locations, bumping into the same people. Rarely is anyone else ever even seen or glimpsed. He keeps living out similar scenarios such as drinks with different people at Martine’s table. Even Vincent’s large house, we only ever see just two rooms at the front. Does Jérémie’s experience in this village represent some kind of dreamlike or purgatory-like place for him?

AG: With Staying Vertical there was an oneiric, dreamlike process in the film because it had such a deconstructed narrative, and you would move from one place to another without any warning. I think Misericordia is something rather different. Despite the fact that it’s a fairy tale-like world and it’s somewhat surrealistic, and there are moments where you wonder whether you’re in dream or reality, with Misericordia I wasn’t trying to create a hallucinatory reality the way I did with Staying Vertical. I’m not sure I quite understand this business of dream and purgatory. You know, it’s like all of cinema, you’re not entirely in a dream, you’re not entirely in reality — you’re in a territory between the two, which I think is something Truffaut said.

PÓM: So, for Jérémie, was he in a kind of in-between place once he gets to the village? Certainly he’s in a transitional place in his life to some extent.

AG: I think that, above all, Jérémie is lost. He’s at a point in his life where he’s lost, and he finds a place where he feels good and he wants to stay, where he decides to stay. The whole film constantly positions Jérémie in this in-between state. It positions him in this very ambiguous way where you never quite know where he’s going, he’s always making stuff up, and even his desire Martine is something that’s not clear, it’s not very clearly defined in his own mind.

PÓM: Like many of the protagonists of your movies, Jérémie is effectively a wanderer. Some of your protagonists have even been homeless. His life in Toulouse is only referred to quite briefly and as something almost historical to him. His wanderings take him back to his past, to the place where he grew up, and where he ultimately finds some kind of love. Is this of any significance to you, that this one of your many wandering protagonists ultimately finds some solace in returning to his past?

AG: I don’t think there’s any significance in that beyond what the film tells or shows us, but what I can tell you is that this is a film where I’m dealing with a lot of fantasies that I had as a teenager, as a young man, and I’m talking about my past. This is a film that has a lot to do with my intimate life. So there’s something like what you’re describing with me. I did look back for this film, and I did return with this film to the place where I grew up. So yes, I wanted to make a film that talks about me in a way that I could share it and universalize an intimate experience.

PÓM: Many characters throughout your films are in search of freedom, be it freedom to pursue their lives the way they want, freedom from obligations, sexual freedom, or, in Misericordia, freedom from guilt. Philipps [the priest] discusses with Jérémie the responsibility of all of us for all of the world’s suffering to some extent. How do you feel about this, about how to reconcile ourselves with that responsibility, and how is that represented by the actions of the characters in Misericordia?

AG: I don’t think that this is represented in the characters of Misericordia, with the exception of the priest, who is conscious of this responsibility we have regarding the woes of the world. I don’t really have an answer to this question because the problem is that I myself feel responsible for not doing anything. I don’t feel that I act with much vigor. I hide from things, I don’t look at the woes of the world all the time. But I also know this, that if one were to live in that way, constantly aware of the woes of the world, it would be impossible to live.

PÓM: You hear sometimes of people talking about art, or cinema, as something that can change the world. Do you believe that there is anything you can do through filmmaking to address some of the woes of the world, or do you believe that these things are separate for you?

AG: Cinema can certainly give us a glimpse of a different way of living, a different way of things. But, concretely, for changing the world, I tend to put my trust more in politicians or unionists or NGO activists than I would in film. I say that specifically about auteur film because I can’t help but think that there are certain kinds of cinema, such as Hollywood filmmaking, which have contributed to changing the world by importing the American way of life around the world. So there is a certain cinema that has affected how we behave and not in a good way, in my opinion.

PÓM: There’s a lot of fluidity in your films, in your characters’ openness, their willingness to explore, their open-mindedness, but also sometimes in certain narrative, stylistic, or thematic fluidity. Do you find that this emerges from your creative process? Do your films change substantially through the process of writing, then filming, then editing? And does this inform their textual fluidity and the fluidity of their characters?

AG: I don’t know what it’s like for other filmmakers, but, in my case, I always searched for this stylistic fluidity, not always with success. But I think I took a big step forward when I understood that a film is made all along the process, through the writing, the shooting, the editing. Early on, I thought that you had to start out with a very strong form that was put in place from the beginning, and that the film really existed from the writing. And I understood not so long ago, I think with Stranger by the Lake, that form is actually found while you’re making the film, rather than before. And the day I understood, that was a big step for me. I also think that with experience, you start to write better, you cast better, you direct actors better, you edit better, you evolve and get better at things.

PÓM: In this movie, at least relative to many of your previous ones, you use a lot of close-ups. I wonder was this a specific stylistic decision, maybe to increase tension, or does this reflect something you feel about the characters, their motivations, their desires?

AG: Actually, I think it’s both things. There was a desire on my part for there to be density, to give the film an intensity, through close-ups of course. But also, each time someone is filmed, they can be looked at, not just seen, by another protagonist. And I think that has a lot to do with the circulation of desire through the film.

PÓM: I felt that, and I felt that there was perhaps a specific purpose along those lines in your decision to use more close-ups and shot/reverse-shots. I also wanted to ask: Misericordia opens with death — there’s a funeral — and it ends with love, and perhaps the closest thing to sex when Martine and Jérémie hold hands in bed. Death and sex have been linked quite closely in some of your previous works, like Time Has Come and Staying Vertical. In Misericordia, there is also the topic of Catholicism with Philippe, the priest. What are your thoughts on the relationship of Catholicism and its ideas about death and sex, and the story you wanted to tell here?

AG: I am of Catholic culture. I’m an atheist, but I grew up in a catholic culture. I feel that I am of catholic culture, and the Catholicism that I’m dealing with here is one where I’m attempting to push its precepts to the maximum — the precepts of mercy, loving your fellow man, understanding the other. And the other thing, which I’m not sure is really felt in the film, is that I’ve come to realize that I really enjoy being in churches. In fact, I recently found myself going to mass again. In that context, I felt the eroticism of Catholicism. I don’t know if this is the case for all religions — perhaps it is but I don’t know them all so well — but I think that comes from the way the religion connects the human body and spirit with death.

PÓM: Finally, it does seem, given that the movie is set pretty much just in this village and the surrounding countryside, as though Jérémie either can’t leave or that he simply doesn’t want to leave. This village, this location — do you feel it embraces Jérémie or does it suffocate him?

That’s a very interesting question. I admit that I hadn’t put those words on the situation myself, but I feel it’s a very good way of summing it up. Because indeed Jérémie is a prisoner of the village, but the village also embraces and welcomes him because it wants to keep him there, through the person of Martine or the priest.

Comments are closed.