Sound of Falling

Melancholy, that inexplicable feeling of pensiveness, constitutes the centerpiece of memory, at least when memory divulges itself to its owner and defers all fantasies of having lived otherwise — in another time or place, or in a manner less harshly consummated by regret or resentment. Infected by this realization, Mascha Schilinski’s phenomenal Sound of Falling suffuses its textures of bare, unadulterated vignettes with the porousness that comes with things half-remembered, events reconstituted, all to permeate the vague and vast gestalt of collective memory. This memory, rooted in the damp, rural landscape of north Germany at a farmhouse in Altmark, straddles both the universal and the particular: over a hundred years, four generations of women are born, live, and die amidst two world wars and the partitioning of the country into East and West. Little of these events, however, are observed, much less consecrated in stone.

In fact, virtually nothing in Sound of Falling comes close to the stony finality sought by most genealogies, and not even the prospect of death takes on such a note. For the women on the farm, death is a factual inevitability, not necessarily a feeling to be experienced firsthand. Taking her cue perhaps from Epicurus, Schilinski inverts the Hellenist’s maxim of disregarding the end into a lingering obsession with and anticipation for it. Young Alma, played with chilly and morbid inquisitiveness by Hanna Heckt, is our narrative’s progenitor, living at the turn of the century in pallid, claustrophobic gloom. At a commemoration of All Souls Day, when the family’s deceased are paraded on the mantelpiece in monochrome daguerreotypes, Alma spots another girl, long having undergone rigor mortis and rigidly posed in frame, with a doll by her side. That girl, her sisters tell her, bears her name; their likeness, as with the faceless blur adorning the woman behind her, opens up an eerie maelstrom of ambiguity.

Such ambiguity does not detract from the clarity with which Schilinski articulates the violence and solitude of her characters. Rather, her camera roves through the achronological membrane of memory, sometimes private, sometimes disembodied, from Alma to Erika (Lea Drinda) during the Second World War, to Angelika (Lena Urzendowsky) in the time of the German Democratic Republic, and presently to Lenka (Laeni Geiseler) and her sister Nelly (Zoë Baier). Across time, milieus blend and morph in a recursive flicker, as uncanny parallels — from stray utterances to the patterns of suffering and sexual exploitation — are made to surface. Having been forcibly amputated by his family to avoid the draft of World War One, for example, the invalid Fritz (Filip Schnack) becomes an object of erotic fascination later on by Erika, his niece, as with the housemaid Trudi (Luzia Oppermann), who is sterilized and rendered “safe” for the farmhands. If Robert Zemeckis’ Here attempted such a survey spatially, affixed to a static camera perspective, Sound of Falling does so more through affect and subjectivity, its freefall rhythm recalling the scintillating narratives of Carlos Reygadas and Terrence Malick.

Yet the film remains singular in its use of negatives, whether through the physical imprints of weathered photographs or through the psychic absences and unresolved plot threads which derail it from a more incurious portrait of phenomenological angst. As an inquiry into the very notion of being itself, Sound of Falling sees its characters uneasily situating themselves within their wider world, attempting to peel away the norms and presuppositions of the era, and summarily failing to transcend the brutal reign of rural, male tradition. “What unites all the characters,” Schilinski has said in an interview, “is the longing to exist in this world for once without anything having preceded them,” echoing the literary criticism of Harold Bloom. Just as the poem is, for Bloom, “not an overcoming of anxiety” but that very anxiety itself, Schilinski’s film underscores the search for — and is — a history specifically overlooked by both cultural exigency and the ravages of time. If W.G. Sebald had written On the Natural History of Destruction to span the 20th century, Sound of Falling would be closest to a faithful adaptation of it.

Scoped wider than Schilinski’s debut feature — 2017’s Dark Blue Girl — and burrowing deep into the bones and crevices of its farmhouse, Sound of Falling may most accurately be read as a hauntological work whose ghostly remembrances and subjectivities, courtesy of Fabian Gamper’s oneiric cinematography, become embodied in the dance of film grain, alternately blurring and coming into focus. But who is doing the remembering, exactly? One may arrive at a tentative answer by considering the film’s three titles: the overwhelming bursts of static in the film alludes to its English title, while its German counterpart, In die Sonne schauen (translated as “looking at the sun”), suggests the piercing, blinding gaze with which the women behold and hand down their generational trauma. Arguably, however, it is the film’s original English title, The Doctor Says I’ll Be Alright, But I’m Feeling Blue, cribbed from a Tom Waits song, that conveys the inexplicable heart and soul of the melancholic disposition. While the nasty, brutish, and sometimes short lives the women lead are directly a product of their oppressive conditions, the film also speaks to a broader existential question. “In truth, I have lived completely in vain” is the sentiment a dime and dozen among the dispossessed, and with Sound of Falling, Schilinski relays it beyond sight and sound, and through the very fiber of memory. — MORRIS YANG

Two Prosecutors

Ever since his debut fiction film My Joy (2010) premiered in the main competition of Cannes, Sergei Loznitsa has been a repeat visitor to the Croisette. Two Prosecutors, his first fiction feature since 2018’s Donbass, marks the tenth time the Belarussian-born director has been included in the festival’s lineup. Unfortunately, what could have been a victory lap and a grand return to the main competition — where Loznitsa was last slotted with A Gentle Creature (2017) — turns out to be a disappointing new entry in the director’s otherwise impressive oeuvre. Following last years’ The Invasion, a perfunctory observational documentary on Ukranian life in wartime conditions, Two Prosecutors regretfully sees the auteur with Ukrainian roots sticking to the surface once again. This could indicate that Loznita’s typically formalistic and intellectual rigor is beginning to falter, as the rich source material for Two Prosecutors is definitely not at fault here.

Georgy Demidov’s eponymous novel about the Stalinist repressions of the 1930s is a jarring dissection of authoritarian tyranny. As a survivor of the Soviet Union’s gulag, Demidov managed to capture in detailed writing the nightmarish conditions in the NKVD prisons. The visceral quality of his prose made the state violence against its subjugated people palpable on an extremely textural level. When the young prosecutor Kornev enters such a prison in 1937 to investigate a letter, written by one of its inhabitants with his own blood, you have already tasted the gore that permeates the Stalinist torture chambers.

With his typically restrained tableaux, shot in the academy ratio to emphasize the layers of suppression within this hermetically sealed environment, Loznitsa opts to peek into the prison from a more distanced perspective. Although the muted greys in the low-contrast cinematography by close collaborator Oleg Mutu hint at the jarring conditions, Loznitsa’s skeletal staging rarely captures the profound existential terror of the prisoners, many of them violently coerced into confessing to political crimes they have never committed. Kornev (awkwardly portrayed by Aleksandr Kuznetsov) witnesses their anguish, but the plasticine set design and stilted performances of lead actors and extras alike rarely translates into moments that capture the dire injustice this prosecutor is set out to battle.

Loznitsa doesn’t seem to be so interested in the human condition here, as he rather explores the taxing experience of navigating this labyrinth of state control. In exacting shots that mimic the process-based mise en scène of Robert Bresson’s A Man Escaped (1956), he peels away the many layers of barred gates, security checkpoints, and peepholes that Kornev has to traverse to reach the ill-fated author of the ominous letter. Especially once Kornev reaches Moscow to address the injustices he has seen to his higher-ups, the mind automatically wanders to Kafka. And to this, it has to be said that Loznitsa made a much stronger appeal to the kafkaesque with his earlier A Gentle Creature, in which he convincingly constructed a near-mythical fairytale around a Russian prison town.

In general, Two Prosecutors mostly functions as a stark reminder of Loznitsa’s better work. With his archival documentary The Trial (2018), he already exposed the Stalinist tendencies to subvert the truth. The internalized colonization of the Soviet people found its apotheosis in his masterful State Funeral (2019), in which Stalin’s funeral procession embodies the moral failure of his political project. Loznitsa’s earlier fiction films about moral corruption also all share his typical formal rigidity, but at least those had some ironic playfulness to them that is sorely missed here. Even in moments where Two Prosecutors does aspire to cynical humor — mostly expressed through the dry jokes of the self-satisfied and unperturbed prison warden — the across-the-board subpar performances of all the actors functions to dull any ironic wit. It all amounts to a prevailing sense of pointlessness that looms over our doomed protagonist, as he dutifully heads to his inevitable demise. As in all of his films, Loznitsa is showing us a lot here about the inner workings of the Soviet apparatus, but rarely has he had so little of substance to say. — HUGO EMMERZAEL

I Only Rest in the Storm

A white person adrift in an “exotic” land, losing themselves in order to find themselves in the perceived primitiveness, peculiarity, or freedom of their strange new locale. A whole world has thus been seen, rendered, and interpreted by European eyes throughout the history of cinema, from the overtly racist adventure films of decades past to more sympathetic (though sometimes equally contemptuous in their depictions of Indigenous cultures and peoples) titles of the 21st century — Lost in Translation, Stars at Noon, Grand Tour, amongst many others.

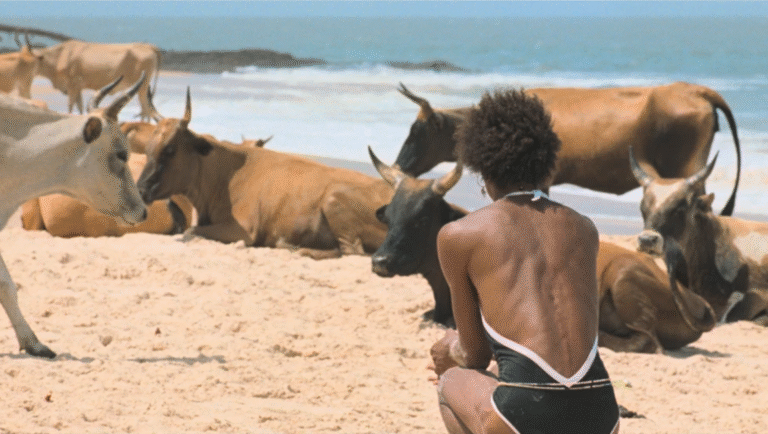

To that list one might now add Pedro Pinho’s I Only Rest in the Storm, in which Sérgio (Sérgio Coragem), a Portuguese environmental engineer, travels to Guinea-Bissau in order to produce a report on the construction of a new road, a project with European financing in a nation with a troubled history of European involvement. En route to the capital Bissau, Sérgio’s car breaks down; by the time he arrives to commence work on his report, he is alone and reliant on the aid of others for almost all his needs and wants in a country in which he is a total stranger. Unmoored, and with apparently little urgency to complete his work, he explores Bissau, meeting a variety of vivid characters who will come to shape his experiences here, and reshape his perspective on life, more than he may initially expect.

It’s far from a fascinating story, not least rendered by European eyes, yet I Only Rest in the Storm is a fascinating film. Pinho is a patient, perceptive, generous filmmaker — no detail is too superfluous to be denied attention or even rumination, no character unworthy of development or compassion, no sequence unnecessary to the overall vision, which is remarkable given the film’s 210-minute runtime and numerous situational deviations. A slow canoe ride through the rural wetlands indulges in a discussion about the price of oysters between figures we’ve neither seen before nor shall see again; a confrontation between Sérgio and a colleague is followed by a further confrontation between said colleague and a local man, again appearing only in this brief exchange. Sometimes, these ephemeral narrative asides are diegetic, as when Diára (Cleo Diára), a woman toward whom Sérgio harbors largely unreciprocated romantic affection, takes him on a mystery trip to spend a day with her family. He only learns of the purpose of this excursion after the fact: he’d previously told her he wanted to get to know her better.

I Only Rest in the Storm is strongest when it maintains some of this mystery, meandering off in surprising directions with uncertain outcomes, or with seemingly no consequence — a shocking incident on a rural road is forgotten within seconds, the ambiguity of this choice adding depth to Sérgio’s story in its lack of clarity. Like him, the viewer spends much of this film slightly on edge, not knowing where Pinho will take us next, nor what meaning it will have, nor even the nature of certain encounters. Romantic developments between Sérgio and several characters are tentative, implicit threats of violence against him generate moments of potent tension, all with no obvious promise of fruition. Good humors and bad tempers, hope and disappointment, acceptance and dismissal intermingle in fleeting moments and long scenes fraught with the contradictions of real-life emotions, and the effect is richly compelling. Rare is such a film that grasps the viewer’s attention so tightly over so long a duration.

It’s weaker, however, when it makes its purposes more overt. Pinho strains a little too hard to negate the inherently paternalistic nature of his European eye observing the actions of his European protagonist in West Africa. A discussion on Guinea-Bissau’s colonial past diverges from the verisimilitudinous tone otherwise established with great sensitivity, feeling both ill-suited to the characters engaged in it, and over-emphatic, a quality that creeps into a few of the film’s more dialogue-heavy scenes. And yet these moments, cumulatively but a small fraction of the film’s total runtime, still contribute to Pinho’s vision in their truthfulness, eloquence, and thematic concordance; their only real flaw is inelegance. Shot in a fluid, observant style, Pinho crafts subtle but impactful stylistic effects from his characters’ environments — a heated workplace argument is intensified by the barrenness of its desert surroundings, a tetchy political debate becomes vibrant in the bustle of a colorfully-lit bar. There’s something to savour in every moment, every element of this deceptively bold film, dense in the breadth of its conceptual concerns and in their elusive, ever-malleable potential meanings, yet swift, light, and blessed with a sweet sense of humor.

Material as accomplished and as lavish with interpretive possibilities as this is a gift to any artist, and Pinho’s care with all departments is evident. The film is scored with occasional lively West African music, accenting but never overwhelming the scenes it furnishes. Similarly, Ivo Lopes Araújo’s cinematography is lucid and graceful, full of striking imagery without ever becoming overly intrusive. And the cast, wholly either non-professionals or actors undertaking the most substantial roles of their career to date, is uniformly magnificent. There’s hardly an aspect of I Only Rest in the Storm that doesn’t feel true, natural, and completely plausible, even when the plot may take a sudden bracing swerve into unexpected territory. It ought to seem as adrift as its protagonist, yet Pinho’s conviction, and the superlative strength of his technical skills, ensure that his project never seems less than sure in its course. This is a truly impressive film. — PADAí Ó MAOLCHALANN

Sorry, Baby

Eva Victor wants you to know that the cat is okay. “I feel like we should have put out a PSA!” they tell me at a recent festival screening. Victor, the writer, director, and star of their debut movie, Sorry, Baby, is referring to a moment in the film in which her character, Agnes, stumbles upon an abandoned kitten in a grocery store parking lot. A Bad Thing had happened to Agnes, and in the wake of it, suddenly reliant on her friends and community for her own wellbeing, Agnes becomes a caretaker in her own right. It’s easy to fall in love with a kitten, but that sensitivity — both Agnes’ impulsive cat adoption and Victor’s insistence that you won’t have to watch it suffer in their movie — serves as a window into Sorry, Baby’s remarkable empathy. Stories on trauma have reached enough of a saturation point to become politically fraught and even occasionally regressive; Sorry, Baby’s finesse proves that tenderness is essential no matter how crowded the landscape.

Agnes is a grad student who lives in a New England college town with her best friend, Lydie (Naomi Ackie). They’re both taking the same writing workshop, but it’s Agnes who wins the attention of their professor, Decker (Louis Cancelmi), who insists Agnes’ writing is exceptional and invites her closer to serve as a mentor. Then, The Bad Thing. That language is deliberate: Sorry, Baby is a movie made by and for survivors of sexual assault, and Victor is careful to note the ways in which language, for better and for worse, holds power as victims navigate trauma’s aftermath.

That’s not to say Sorry, Baby is at all avoidant; in a standout monologue, Agnes details every harrowing moment she’d suffered with Decker, and those in her orbit less equipped or inclined to approach her assault with compassion (doctors and court workers among them) don’t hesitate to use language Victor knows might sting fellow survivors. Victor’s tendency to both acknowledge the painful realities of an act of violence and approach their audience gently is a balm in a moment in which sensitivity has been co-opted and lambasted by a host of bad actors. It’s a tightwire act and a welcome reminder that taking care around language supersedes conservative eyerolling and disaffecting algospeak, that the words we use concern and affect the people around us.

Sorry, Baby is divided into five, non-chronological chapters: We first meet Agnes and Lydie in Agnes’ New England home, Agnes having become an English professor at their alma mater, Lydie returning to share news of her pregnancy. Their time together is briefly interrupted by Gavin (Lucas Hedges), Agnes’ Ohiocore neighbor and budding romantic interest who serves as a formidable complement to Eva Victor within the film’s comedic engine. The movie’s unconventional sequencing is considered and precise, a fine showcase for Victor’s capacity to construct a story less bent on emotional devastation than providing a sweatless hand to hold. But it’s also a testament to the fragments of trauma that endure even as one works to reconstruct a life. There are wisps of the yet-defined Bad Thing even through Agnes’ and Lydie’s happy reunion — a diverted glance here, a panic attack there — and as she leaves to return to New York, Lydie gives Agnes a command as simple as it is severe: “Don’t die.”

Tracing the borders of a life after an assault is an impossibly heavy task, which makes Sorry, Baby’s thrilling sense of humor all the more miraculous. Somehow, this movie about an enduring trauma is gunning for — and scoring — laughs at the back of the room. Eva Victor first broke into the spotlight through comedy, crafting front-facing videos and stand-up and spinning headlines for The Reductress, and those hard-won sensibilities show their face in the movie’s expert timing and punchlines. Watching Agnes lie her way through a meet-cute with Gavin churned enough laughs to miss lines during my screening, and Victor’s presence positions an otherwise dour courtroom scene into one of the film’s funniest moments. In a rare instance or two, going for the joke skirts the lines of plausibility; the aforementioned moment with an insensitive doctor recalls Broad City’s duller polemics. More often, though, Sorry, Baby’s comedy is brilliant, another reminder of the movie’s insistence to sit there beside you through it all.

Victor’s background in comedy may have equipped them to approach Sorry, Baby, as a multihyphenate, but the movie is far from a solo effort. “When you’re a multihyphenate, you’re forced to ask for help a lot and to rely on those around you. Those people end up wearing multiple hats, too,” Victor tells me. “You write a movie privately, where it’s just you and the page, and eventually you end up in this whole group of people directing it.” Part of what helps to separate Sorry, Baby from the myriad coming-of-age stories content to posit trauma as a MacGuffin is its quiet strength as an ensemble piece. Ackie’s Lydie is a portrait of compassion and the sort of testament to female friendship that warms Pedro Almodóvar’s oeuvre; Louis Cancelmi balances writerly prestige and menace on the same fingertip; in a career of scene-stealers, John Carrol Lynch enters late into the picture to remind you of his muscle as an ace in the hole. That care in casting reflects Sorry, Baby’s belief in the role of community in healing. The movie is smart to avoid life-goes-on flavored platitudes; it becomes excellent in its curiosity toward the way relationships break and bend and bloom after the unthinkable. — CHRISTIAN CRAIG

The Girl in the Snow

The titular girl of The Girl in the Snow, director Louise Hémon’s debut feature, appears repeatedly as a dark silhouette. Clad in a black cloak and hat against a blazingly white landscape — and often in a long shot obscuring her features — she stands in stark relief to her surroundings, at once clear as a symbol and difficult to read as an individual. This image is an effective metonym for the film it appears in: just as, in this reiterated shot, the girl is both revealed and obscured by the environment she is visibly separate from, the film unspools like a parable of how meeting one’s supposed opposite can both uncover repressed truths and render illegible one’s existing self-conception.

The Girl in the Snow, written by Hémon and Anaïs Tellene with Maxence Stamatiadis, follows a young, secular school teacher (Galatéa Bellugi) who has taken a position in a remote village in the French Alps, just before 1899 recedes to make way for a new century. She begins her assignment with vigor and utter conviction in her own moral and intellectual correctness, but the resistance of the villagers, who have their own closely held convictions that often oppose hers, stymies her efforts. She eventually relaxes her judgment and becomes more of an equal member of the community, which coincides with her own gradual acknowledgment of her sexuality. Yet strange consequences follow these changes in her personality: when she has a sexual experience, avalanches and unexplained disappearances tend to follow.

The film is set over the course of a long winter, and director of photography Marine Atlan highlights the vast, icy grandeur of the mountainous setting by using a cool color palate and periodic wide shots of the landscape — an aesthetic approach which brings to mind Mikhail Krichman’s photography for Maura Delpero’s Vermiglio, another artfully crafted film with an Alpine setting. Yet Bellugi brings a simmering heat to her performance as Aimée, the teacher; she is initially given to bursts of excitement to teach the children or pique at her frosty reception by the community, and she later bubbles over with desire. Bellugi’s spirited performance, evoking both her character’s energy and naïveté, is a canny counterbalance to the more reserved, skeptical villagers. While the film’s gelid, often shadowy look is aligned more with the hidebound rural community than the would-be-reformer Aimée, the scenes involving her sexual awakening come closest to adopting her perspective in a visual sense — particularly a narratively crucial sex scene between her and a local boy, Pépin (a reserved, yet magnetic Samuel Kircher), in which their foreplay involving a map and a magnifying glass is bathed in warm, sensuous lantern light.

Just as the narrative makes some unexpected turns — particularly following the pivotal sex scene between Aimée and Pépin — the film features a number of unconventional aesthetic choices, most prominently its distinctive score. Composed by Emile Sornin, this score is a jangly blend of strings, percussion, and staccato voices singing in unison, with chromatic melodies that clash and dip into minor keys. Sometimes this music imbues scenes with a dark whimsy, while at other times it lends an incantatory quality. In a New Years’ party scene, the most festive in this emotionally turbulent film, the score is even diegetic — two revelers play instruments that underscore a joyous social dance. The score and sound design also emerge to the fore in a scene where a feverish Aimée recovers — aided by folk remedies, including a beheaded chicken placed on her chest — in a half-conscious daze; music mingles with the sounds of human voices and farm animals, becoming muffled and distorted as if Aimée were underwater. (In fact, the film’s French title, L’engloutie, translates to “The Submerged.”)

The cumulative effect of the film — with its formal and aesthetic idiosyncrasies, its narrative drift into unreality — is, if sometimes puzzling, ultimately enrapturing. Aimée’s transformative foray into the mountains occasions a plunge into what she has repressed and excluded from her life — namely sex, death, and the unpredictability of nature — breaking down her identity before she can escape with the thaw of spring.

Though Aimée is the film’s focus, Hémon hints at how the community she leaves behind may think of her after her departure. They are shown throughout the film to have a strong tradition of oral storytelling, sharing fables of Death visiting men in the form of shadows and seductive women attempting to drag men off cliffs. One can imagine, years later, the children who were taught by Aimée telling the story of the intruder who seduced and preyed upon members of their community and attempted to destroy their way of life. It is a fable with two opposing sides, irreconcilable perspectives that nevertheless shed cold light and cast unnerving shadows on each other. — ROBERT STINNER

Dandelion’s Odyssey

Biblical scholars and theologians use “antediluvian” to describe the world of Genesis between the fall from Eden and the flood. Literally meaning “before the flood,” the word packs grand meta-narratives of historical and cosmological significance: humans fumbled the chance to live in paradise for good and brought down our world with it. Disaster awaits, monsters lurk. The beauty of the original creation still radiates brightly in the meantime. This is the world that Momoko Seto’s Dandelion’s Odyssey drops into. Four dandelion achenes — named Dendelion, Baraban, Léonto, and Taraxa in the marketing notes — survive the end of our paradise and toil through space, evade danger of both seasonal and lifeform varieties, before eventually rekindling their species on another planet. Yes, you read that right: this is an animated film without words about dandelion seeds traversing the cosmos in search of a new home.

For a fleeting moment, the natural world looks peacefully Edenic. Two dandelion balls capture Seto’s attention, tilting slightly with the wind and reacting with a smidge of anthropomorphism to their surroundings. The green and lustrous world they inhabit is so peaceful that it disturbs, and the droneish score helps to facilitate that uncomfortable feeling as vague sounds punctuate the music to scratch a sci-fi itch. Eventually, the flood comes. Red balls fly through the periphery and crash in the distance, the world engulfed in red atomic terror. One dandelion ball floats above the fire and into deep space. The ball has no chance against the uncertainty and vastness of the galaxy, and it gradually loses its shape. Only the four seeds remain.

The animated seeds move not unlike the food characters in Veggie Tales, with their cluelessness and kitschy bobbing. They are human enough to react to the dangers before them with movements of their own, and plant enough to never speak. It’s a weird lane to occupy, and made even weirder with the stylized animation that still undoubtedly leans toward photorealism, even if the cinematography doesn’t always. Any verisimilitude undergirding the photorealism is abolished just moments into the film as the dandelion survives flight into outer space and floats past giant space squids.

The entire odyssey breezes by. The film lasts only a quick 75 minutes, and there are more location pit stops than your average Fast and Furious film, making each minute feel shorter than 60 seconds. But the dandelion’s venture into space as it breezes past our moon and away from our sun misses the opportunity to deliver an emotional effect. Any sense of isolation, wonder, desperation, or fear dies with the planet. Audiences need to spend time in space to feel its isolation, and the same goes for any other chapter in the odyssey for that matter — but the time lapse cameras and effects Seto relies on try to cheat by erasing the effect of time passing while still reaping the benefits. Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman quite humorously once said, “When most people go to the movies, the ultimate compliment—for them—is to say, ‘We didn’t notice the time pass!’ With me, you see the time pass. And feel it pass. You also sense that this is the time that leads toward death. There’s some of that, I think. And that’s why there’s so much resistance. I took two hours of someone’s life.” Seto and Akerman aim for totally different projects, of course, and these differences might force an unfair comparison, but Akerman’s artistic relationship to time points to a larger truth about cinema’s intrinsic and manipulative relationship to time. Feeling its passing in Dandelion’s Odyssey would have left the achenes’ journey more freighted with meaning.

The end trajectory for the dandelions is technically that of an invasive species. From a biodiversity standpoint, they threaten their new home. Empathy translates the environmental risk into a story of refuge. The homeless Dendelion, Baraban, Léonto, and Taraxa hang onto their life — or, technically, the possibility of life, since they are seeds — by a thread until they secure a new place to belong. The motivating impulse for Seto appears to be more about the interdependence of life on earth. The directed stated in an interview for Cannes’ La Semaine de la Critique that she hopes audiences take away “That nature is not a backdrop to be trampled, that it is not separate from the self, that all the little things that surround us are the actors of an action film, that a growing plant is so beautiful that it can make you cry. We are all a force of nature, bound to one another, and together we make up our planet.” This means the film works better as a metaphor for lost humans than anything to do with other lifeforms, however, especially with rising global conservatism about refugees and migrants. The seeds, totally dependent on systems outside of their control, can do nothing but blow away with the wind and hope for the best. Their fate lies outside of their hands; their ability to find belonging is something they have no ability to manipulate.

The film’s French title is Planètes and directly places the animated journey in continuity with Seto’s Planet shorts: Planet A, Planet Z, Planet ∑, and Planet ∞. All of those films bridge the natural world, and in particular evince a fixation on smaller life forms, with semi-experimental animation influenced by nature documentaries. Seto has also made a series of animal-lovemaking films that she labels “porn” on her website. Unfortunately, too little of that ambition and nerve has touched her latest project. Dandelion’s Odyssey may begin with nuclear destruction and the end of the Anthropocene, but it’s nonetheless a far tamer outing than viewers can find in the director’s other work. — JOSHUA POLANSKI

Comments are closed.