Drifting Laurent

The world of Drifting Laurent, the sophomore feature by directors Anton Balekdjian, Léo Couture, and Mattéo Eustachon, is not too dissimilar from that of Alain Guiardie’s Misericordia from earlier this year. Both films contemplate the nebulous desires of a sexually fluid drifter who turns up in a small, sparsely populated town filled with quirky characters and beset on all sides by tenuous interpersonal relationships. Each, too, is fascinated by the empty spaces of nature, and of the possibilities of discovery in a place that at once represents a fresh start and carries the burden of history. Laurent’s (Baptise Perusant) slippery identity doesn’t portend dark events in the same way the protagonist of Guarardie’s film does, but his lean, handsome face and charmingly awkward demeanor means he is both an unremarkable presence in his often indifferent surroundings, and perfectly suited to the social and romantic pursuits he’ll undertake over the next few months.

If anything, Laurent’s relative innocence makes him alluring. Like the prized magical goat — said to produce milk all year long regardless of pregnancy — that a local farmer has tragically lost, he’s an exotic quantity, an oddity amongst a community of hard-nosed cynics. Laurent falls in with Sophia (Beatrice Dalle) and Santiago (Thomas Daloz), a mother and Viking-obsessed son who live full-time in the ski town. He ends up staying with them for a longer than expected when the irrepressible tug of the job market beckons his fair-weather friends to distant shores. The trio’s relationship is sweeter and more complicated than any other Laurent forms during the film. At one point, Laurent sleeps with Sophia, much to the dismay of the regressive, incel-lite Santiago. It’s difficult to tell whether Laurent’s good-spirited accommodation of Santiago’s childlike impulses, like screaming “for Valhalla” to the sky and building virtual colonies on a Google Maps-like interface, is meant to preempt or make up for his affair with Sophia.

Laurent’s pursuit of new social and romantic relationships is founded upon an unspoken desire for community. On his first night, he discovers an old woman, Lola, sitting in the freezing cold in her nightgown, an attempt on her part to kill herself. “I’m fed up,” she tells Laurent after he tucks her into bed. Alone in a lonely town, we’ll soon sympathize with Lola’s state of mind. Laurent also meets and starts a romantic fling with Farés, a photographer working in the town during the off-season. Their introduction, during which Farés cheekily convinces Laurent to strip naked for a photograph, is played for laughs, but it’s effective in portraying Laurent as the kind of guy either too accommodating or too gullible to survive in the real world. Laurent’s sentimental tendency to form attachments is ill-suited to the realities of the seasonal gig economy, where the need to pack up one’s life at a moment’s notice and move to a new city is not just some romantic quirk, but an economic imperative. Eventually, Farés will leave for Marseille; the vague hope Laurent might join him later, however, disappears entirely.

Balekdjian, Couture, and Eustachon have a patient style that suits the culture of limbo in an off-season ski town. The wide-open spaces, the prolonged silences, contemplative and serene, provide space for the viewer to think about productivity. What is the point of being productive, Laurent might have asked himself, when the screaming kid he’s helped after falling off the ski lift kicks him in the shin? What, too, is the point if there’s another home he can settle himself into with ease? If there’s an answer, the filmmakers haven’t exerted much effort trying to spell it out, though there is something to be said for the fact that for most of the film Laurent also contemplates productivity that actually is productive. Instead, the sly commentary of Drifting Laurent — whether on the toll of transience and inconsistent employment, or on the cost of isolation — can be found wandering the grounds of the resort itself, braying and jingling its bell. Laurent catches a glimpse of it himself, though there’s no telling whether he listens. — CHRIS CASSINGHAM

Bulakna

The Philippines, an archipelago of over 7,000 islands, comprises diverse ethnic groups with an equally diverse array of beliefs, languages, and customs. Comparisons to the geographical make-up of Indonesia are certainly in order, and yet, geopolitically speaking, the trajectories of both countries appear differently fated under the auspices of globalization. Whereas Indonesia, a proud founding member of BRICS, has broadly shaken off the vestiges of its colonial exploitation under the Dutch, the Filipino narrative augurs unwilling nostalgia for — and possibly dependence on — an antiquated world order. Reverence for America does not necessarily loom large, but its lingering implications do: a de jure democratic presidency, steeped in patronage and authoritarianism, has recreated with grim reverence the “shining city on a hill.” Antiquated though its loyalties may be, the Philippines is awash under global tides, its industrial dependence on agriculture a hurdle to economic supremacy, and its Anglophone demographics a convenient supplier of cheap, easy labor for the First World.

These observations are indirectly appraised in Leonor Noivo’s Bulakna, a compelling examination of the insidious ways capitalism and colonialism thrive off each other. Part ethnography and part memoir, the film draws its title from Reyna Bulakna, the mostly forgotten wife of Lapulapu, himself a national hero of the Philippines for having successfully repelled the advances of Ferdinand Magellan in the 1521 battle of Mactan. A reenactment is staged in Noivo’s feature, with a theater troupe injecting additional discourse on the socio-cultural dynamics of indigenous life prior to the eventual Spanish conquest, if only to set up the mythological framework for the film’s resolutely modern reality. Life today, especially for the women, hinges on a realization of a pipe dream to work abroad and earn a competitive, even bountiful wage. Melissa (Althea Mariz Aruta), a young woman who ekes a living on the island of Mindoro selling fish, considers going abroad to seek employment as a maid. Though the term “domestic helper” gratifies liberal sensibilities better, the bitter irony of domestic work in a foreign land — where helpers, for one, leave their families and kids behind for years on end — is not lost on those who don its mantle.

Melissa’s cautious and almost resigned optimism is gently juxtaposed with the weathered reminiscences of Norma (Norma Linda Canda), an older woman and former journalist who gave up her job to work as a domestic helper in Lisbon, Portugal. In staid voiceover, she lists out a series of rules, perhaps informally scripted or officially designated, for prospective maids to adhere to; the “more invisible you are,” she maintains, the “better your work is.” Apparent here is the discreet othering of selves, whether workers, women, or those indisposed by birth to the cocooning embrace of whiteness, and as this othering takes place seamlessly abroad, the effacement of local histories, familial ties, and love lives proceeds in an air of unspoken disquiet. Maids are not yet refugees amidst the hierarchy of the global precariat. But like Bulakna, their precarious diaspora has already been perched on the edges of oblivion. In humanizing the labor that feeds the invisible grist mill of capital, Noivo’s film solemnly stages a noble lament. — MORRIS YANG

Death and Life Madalena

In the tradition of Day for Night, Brazilian director Guto Parente’s new film Death and Life Madalena follows the production of a film beginning to end with ebullient humor. As in François Truffaut’s classic, constantly occurring obstacles keep the film-within-a-film always in a precarious position, yet the cast and crew’s earnest commitment to the shared project always keep it alive for another day. Parente’s film has its own distinctive artistic identity, though, and the film he crafts is as much a love letter to scrappy low-budget cinema as it is a celebration of artists whose identities and lifestyles place them on society’s margins. Anchored by a tremendous leading performance by Noá Bonoba as the titular protagonist, Death and Life Madalena is a warm-hearted, cinephilic comedy centering the messy and idiosyncratic joys of artistic collaboration.

Madalena, called Mada by her friends, sets out to produce her filmmaker father’s final script, a sci-fi B-movie, soon after his death, working on a shoestring budget while she is eight months pregnant. Her partner, Davi (Marcus Curvelo), is set to direct, but after he abandons the production, Mada recruits eccentric actor Oswaldo (Tavinho Teixeira), a close friend of her father’s, to take his place — only after two of her more trusted collaborators turn down the opportunity. In between medical check-ups, Mada struggles to get the money meant to pay her cast and crew released from the bank, and has even greater difficulty managing Oswaldo, whose scattered, bacchanalian directorial style is unproductive at best: Mada’s assistant director and close friend, Natasha (Nataly Rocha), shows her a video of Oswaldo stripping atop a speaker during what were supposed to be shooting hours, leading to a confrontation where Mada utters the indelible line “Kubrick would never stick his arm up his ass on top of a sound system, Oswaldo!”

Grieving the loss of her father and preparing to usher new life into the world, Mada is at an inflection point, and her reflections on her life provide a subtler counterpoint to the production’s pandemonium. Utilizing several cinematic devices, including simple conversations and phone calls to loved ones, but also fully staged flashbacks and a surprising and well-crafted animated sequence, Parente provides glimpses into Mada’s past. After the death of her mother in a car crash, she spent much of her childhood on film sets with her father, which sparked her imagination and provided a safe and convivial environment, even after traumatic episodes. Now, pregnant with a child that we learn early on is not Davi’s, Mada’s commitment to the completion of her father’s film is not only an act of commemoration, but an expression of deeply held love for her father and her passion for the process of filmmaking.

Bonoba excels in all aspects of the layered character she plays. When working, Mada tries to maintain a veneer of calm that gets broken down incrementally with each new obstacle, and Bonoba performs the rage and frustration that inevitably burst forth with full-bodied energy and precise comic timing. She is equally adept when called on to portray quieter moments of grief, intimacy, and tenderness, communicating a vivid interior life and emotional complexity through subtle facial and vocal modulations. Bonoba’s performance is at once dynamic and disciplined, grounding the film in a compelling emotional reality and allowing actors in more broadly comedic secondary roles to go big and bold — particularly Teixeira, whose Oswaldo is a mostly endearing, occasionally frightening chaos agent.

The cast of characters, like the film’s actual cast, includes many queer people. Parente has remarked that “queer cinema is a cinema that inspires freedom, that seeks to displace borders, to tear down moral walls, and my interest in it is both aesthetic and political.” The collective effort by a sexually- and gender-diverse crew to craft a low-budget, campy sci-fi movie is a delight to witness, both in the comic situations that arise and in the very “freedom” Parente portrays in this fictional production. The mode of collaboration on display in Death and Life Madalena is not one without power structures, conflicts, and poor behavior — Parente is not staging a utopia, and in fact portrays several ethically troubling moments on set — but it does include close collaboration, malleability in the roles played by individuals, and a collective sense of care. The politics of this dynamic, like the film’s queerness, are not explicitly pointed out but are ever-present, providing a vision of the kind of aesthetic, moral, and communal freedom Parente seeks to inspire. What is ultimately most moving and joyful about Death and Life Madalena is that, at least in the emotionally and artistically vibrant world Parente cultivates, the love of cinema and the love of one’s community are one and the same. — ROBERT STINNER

The Dam

“Lebanese filmmaker Ali Cherri has been a bit of a fixture on the festival circuit with his wry, melancholy short works addressing the state of the Arab world. His 2011 film Pipe Dreams was a miniature triptych about the hopes and failures of the Arab Spring, and his slightly longer film The Disquiet (2013) examined instability in Lebanese life, both on a cultural and a seismic level, literalizing the concept of a society breaking along various fault lines. With all this in mind, anticipation was high for The Dam, Cherri’s feature debut…” [Previously Published Full Review.] — MICHAEL SICINSKI

A Thousand Waves Away

Helena Wittmann is likely best known for her feature-length narrative films Drift and Human Flowers of Flesh, but she has been making small-scale, idiosyncratic shorts for over a decade, often working as her own cinematographer. Her newest film, A Thousand Waves Away, is only 10 minutes long, but it’s a mysterious, evocative bit of abstraction, conjuring a strange interior universe via minimal means. Set to an incessant, droning loop by musician Nika Son (an electronica artist who has worked on almost all of Wittmann’s films), titled Indefinite Cupboard, the film is a series of mostly static shots of human figures performing ritualistic activities in a wooded area surrounding a waterfall. A series of interstitial title cards act as a sort of accompanying poem (or song lyrics), suggesting hints of a narrative shape that never actually coalesces. The first title card reads “a thousand waves… ago” and is followed by a shot of hands picking flowers, then a silent, motionless figure standing amidst the trees. There are several closeups of hands, legs, feet, the compositions arranged so that the edges of the frame cut off large swaths of the figure’s body. One shot features a pinecone “falling up” into someone’s hand, followed by another title card that reads “in a place where much… no longer made sense.”

Here, then, is a place where cause and effect are seemingly reversed, and as the musical accompaniment grows louder and faster, the film begins to take on the patina of a horror exercise. But Wittmann’s lovely images are too inviting to be labeled scary; shooting on what appears to be 16mm film, there’s a very particular quality to the light here, an unforced naturalism that runs counter to the Bressonian models on display. The greens and reds of the foliage are rich, even lustrous. Pools of water reflect shimmering light, and closeups of rocky, granite-like textures are so detailed one feels like they could run their hand over them. At one point, one of the performers hears an airplane flying by offscreen and looks up; the film cuts to an image of a cloudy, opaque color field that one first assumes is the sky. But Wittmann holds the image long enough for viewers to discern that it is the surface of a lake. A simple enough trick of continuity firing, but it is uncanny in its effect.

Eventually, one of the figures begins traversing a path away from this space, first passing a bronze statue and then, finally, encountering civilization, represented here by a large park with an ornate fountain and several large buildings visible in the background. Is the person merely passing through? Are they running away from something or toward something? It’s hard to say. A Thousand Waves Away is as fixated on water as both Drift and Human Flowers of Flesh are, as a kind of freeform visual metaphor that takes on multiple meanings in her various works, but much like Angela Schanelec (who Wittmann is sometimes compared to), she never gives in to total experimentation, instead referencing various (mostly Structuralist) influences and erecting her own strange scaffolding around them. Waves ends with closeups of a strange sculptural object spinning in front of a black background, its various spherical protrusions reflecting glints of golden light across the frame as water drips from it. It’s lovely, a beguiling moment, these flickers of light dancing and refracting into abstraction. She then cuts to a pair of hands, the dancing golden light framed in between them to appear as if the hands are summoning them, or perhaps commanding or containing them. It is, ultimately, a strange ritual that we are witnessing, as if Wittmann is inviting us to experience a moment we cannot fully comprehend. This is a sketch of a film, a trifle even, but like many experimental shorts it allows us access to something like an artist’s thought process playing out almost in real time. Unburdened by the logistics of creating a feature-length project, instead we are given this odd, beautiful alchemy. — DANIEL GORMAN

Still Life Primavera

The ever-varied and ever-botanically-focused Pierre Creton’s Still Life Primavera finds the director making one of the structural experiments that he previously dabbled in with films like House of Love (2021), where he placed his camera on a record player and let it spin away to make something with the manipulative wit of a Michael Snow film. The camera doesn’t appear to move at all this time around, but it once again looks out a window: there’s a lit candle as the only object visible, but we’re being tricked when it turns out to just be its reflection against the glass as the countryside trees outside the window become more visible. Nighttime turns a window into a mirror of our interiors, but daytime allows us to look out at the world. When the sun comes up, the camera remains unmoving as it looks out at the resulting springtime still life of the title, but odd edits every minute that allow animals to suddenly materialize in the frame and the light to shift as needed draw our attention to the small manipulations of time that Creton is performing.

The sudden appearance of a donkey, and a shot of the fog blowing by, recall one of the most famous films operating in the single-take mode in Larry Gottheim’s Fog Line. What this film creates out of stasis, however, could be considered a new form of in-camera editing that separates it from your standard long takes and turns it into a deliberate highlight reel. Further evidence of how much control is being exercised over this seemingly uneventful “shot” comes from inside the room, when a pet cat and Creton’s hand holding a flower pop into the frame from inside the camera’s room, followed by a needle drop from a band with the revealing name Eyeless in Gaza. Night falls again, and the window becomes a new kind of mirror: one that reflects a laptop displaying images of death and explosions from the current genocide in Palestine, with Creton’s hand once again reaching out to touch the screen. It turns out that all this time spent staring out the window was not so much a lazy stare as a form of vigil of remembrance, with Creton’s candle and flower being small funereal gestures for all the dead murdered by Israel in Gaza. It has been a full day of more needless death and pain: one unfortunately has to light another candle. — ANDREW REICHEL

Poétique de l’eau

Although they are not programmed together at this year’s edition of FIDMarseille, it’s nonetheless intriguing to encounter Christine Baudillon’s Poetique de l’eau alongside Helena Wittmann’s A Thousand Waves Away; both films are fascinated by water as a poetic device and a powerful ecological reality that dictates human life while acting as a repository for all manner of religious, superstitious belief. Poetique de l’eau , or simply Poetics of Water, flits between an experimental mode and an essayistic one, featuring voiceover narration by Baudillon herself and Jean-Christophe Bailly, reciting passages from Gaston Bachelard, Edgar Allan Poe (translated by Baudelaire), Baily’s own writings, and, for the epilogue titled “a pretty Fly,” archival footage from Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter. Clocking in at just under an hour, it’s dense enough that transcribing all of the voiceover is impossible, as is full comprehension of all the philosophical interjections that unspool at such a quick pace. But the film is very effective at creating and sustaining a mood, a kind of lulling quietude that allows viewers to fully succumb to the quiet rhythms of lapping waves and gently billowing grass.

The film begins with a shot of a dead cat in a box submerged under a pool of shallow water. The camera is facing straight down, catching the reflection of the looming sky on the surface of the water, which creates a kind of shimmering, superimposition effect. It’s sad, of course — we are not used to being confronted with a dead domesticated animal in the opening seconds of a film. But the moment becomes calming, natural even, as we register the idea of something organic returning to nature in a respectful, ritualistic manner. A flower has been arranged beside the cat inside the box, suggesting some love and care in its handling. A dedication follows, which reads “to his majesty Bebop, this cat, this joy; to all animals and otherness, flowers, trees, stones and rocks, winds, streams, rivers and seas, to the coming night.”

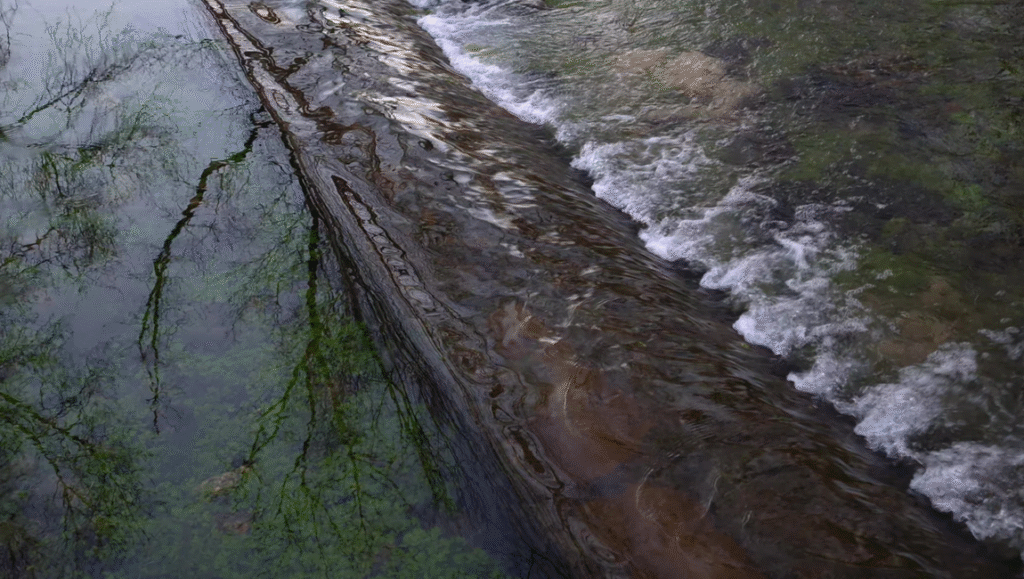

From here, the film proceeds as a series of largely static master shots, in which Baudillon frames the horizon line in different ways and finds naturally occurring symmetries via protruding objects and drift wood. A sizeable log is arranged parallel to the shore line in multiple shots, suggesting the bifurcated compositions of a Rothko painting. Strange-looking pieces of gnarled wood jut out of the placid surface of the sea, reaching toward the sky. There are multiple shots of waves crashing against the flat shoreline, as well as the occasional cut away to fields of tall grass swaying gently under the breeze. The widescreen images are suffused with every shade of blue, the sky occasionally blending into the surface of the water.

All of this is accompanied by voiceover commentary, a constant stream of philosophical mutterings that wash over the viewer a little too quickly. It’s difficult to process the images and the words simultaneously, meaning that one or the other is demanding attention to the detriment of the other. As an example, one long passage begins, “the language of the waters is a direct poetic reality; that streams and rivers provide the sound for mute landscapes, and do it with a strange fidelity; that murmuring waters teach birds and men to sing, speak, recount; and that there is, in short, a continuity between the speech of water and the speech of man.” The cumulative effect of all of this aural and visual information is an overriding sense that Baudillon is attempting to arrange nature into a more digestible aesthetic object, denying the unpredictable power of these elements — wind, water, mana — in favor of a more carefully curated experience, even anthropomorphizing it in some ways.

The filmmaker seems to recognize this, at least to a degree, and toward the end of the film switches from her own voice to that of Bailly, who proceeds to announce an entire taxonomy of every single kind of water, from the naturally occurring to those influenced by human intervention: “river, canal, puddle, pool, jet, reservoir, eddy, pond, lake, fountain, aqueduct…” and so on. Here, the film cuts much more rapidly, interjecting finally some signs of human activity. It’s a rousing finale, suggesting all the ways in which we encounter water every day, even when we are not consciously recognizing it as such. For all its patience, Poetique de l’eau is admittedly too fragmented to land with real authority; its philosophical underpinnings would be better served on the page rather than the screen. But it’s nonetheless an extremely pleasant object to look at, and for those able and willing to succumb to its quiet rhythms, there is much to enjoy here. — DANIEL GORMAN

Comments are closed.