“You tell me things I never found in Plato or Hegel.” Romantic expressions like this abound in Isiah Medina’s latest, Gangsterism, a film noir set in the seedy world of Canadian film grants and Spielberg apologists. The streets are adorned with Star Wars prequels posters, and, at any moment, a jury panel may spring from the darkness and arraign you on charges of misreading the legacy of D. W. Griffith.

Such are the pleasures of Medina’s remix of cinephile culture in the year 2025. Like his previous works, Gangsterism eschews the natural world for one in which every character can debate the insights of Tag Gallagher and shred the works of Hegelian scholars. The director, Clem (Mark Bacolcol), must make a new film by rejecting the infrastructure and received wisdom that defined filmmaking in the 20th century. Also, he needs his money back.

This is an essai in Montaigne’s original use of the word: an attempt at thinking through cinema by means of cinema. Intellectual history and cinema history collide here in a constant salvo of flickers and cuts and names and quotes. After the dust settles, we’re asked to pick up what’s left and forge a new way forward.

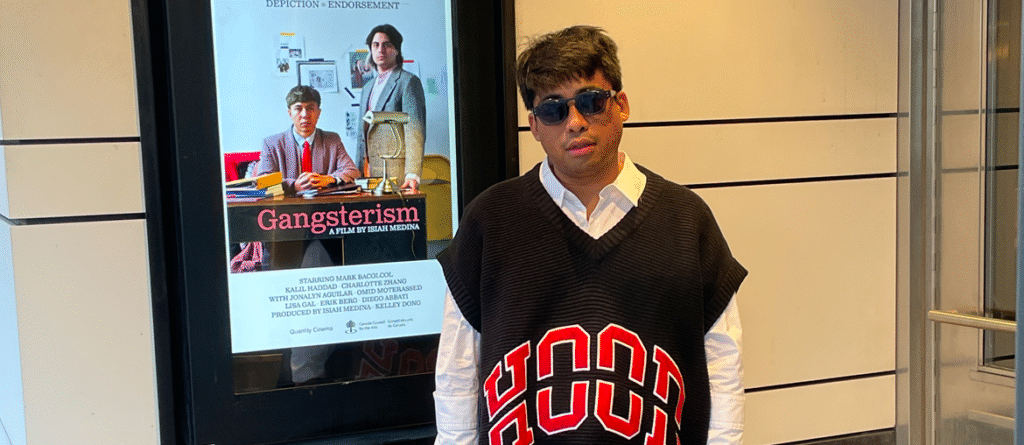

Over Zoom, I spoke with Isiah Medina about Gangsterism, a couple of Pittsburgh philosophers, and what it takes to make a movie.

ZACH LEWIS: Whenever I was watching Gangsterism, I was trying to play that critic-brained game of thinking about the previous Isiah Medina movies that I’ve seen and how this relates to it. But, as somebody who’s constantly looking forward and trying to do something new with cinema, are you concerned with the things you’ve done previously and how they’re affecting the new movie?

ISIAH MEDINA: Oh yeah, for sure. Because my relationship to what I did before changes, and I only will know what I did retroactively in the next picture in some deep sense. I’ll think, “Oh, that’s what I was trying to do there because now I’m figuring it out here.”

I always like to use this example of Brian De Palma, where he would almost, in essence, copy moves from Hitchcock and then copy his copy. And by doing that, he gains autonomy and starts reinventing himself through himself. So this one, especially with Gangsterism since it’s about filmmaking, I did think about the stuff that came before.

Kinda like with infinities, the next one has to subsume the previous one to contain its size. Like after 88:88, I’m like, okay, I really pushed a dissociation between sound and image to a sort of limit, so I wanna reintegrate sync sound in a new way with Inventing the Future. And after that I’m like, “Okay, I really push a certain type of montage in a sort of way,” and in Night Is Limpid let’s really push for what can experiment with dialogue. And then by He Thought He Died it’s, “How do I reintegrate some of these montage questions back into dialogue?”

And then in Gangsterism, I try to combine all that again and invent some other moves I haven’t tried yet. So I definitely do think about it just because it’s not only that I’m trying to explain myself to someone else — I’m trying to explain myself to myself. I’m trying to figure out what the hell’s going on, so I have to take an honest look at what I did before and why I did it.

Last night, I saw 88:88 for the first time in three years. I’m like, “Oh wow, some of these ideas I take further in Gangsterism. You never know where the seeds of it happened first. And even just seeing that last night, I realized that some of the stuff about finance markets and derivative markets and all these other types of questions about the economy really come into fruition in Inventing the Future. And then from there, Night Is Limpid is a little bit about Covid and quasi-UBI that people got during that time. And then with Gangsterism, I can see how I got from one place to another.

And that was really important to me because it’s a way to see how you’re growing in time. When I edit movies, I often have a different picture in the background, just in silence. I love The Aviator. I’ve seen it like a hundred times. It’s one of those things that when I see DiCaprio in his court case about his spending in relation to the big airplane, I’m like, “Oh, I guess two hours have passed now.” I clocked relaying what’s on screen, and I feel like when I look at my own movies, I could just tell where my life was and where I’m trying to go next by these charged decisions.

Lately now, I always try to make at least two or three pictures at the same time. When I finished He Thought He Died, I was showing it, and then I finished the screenplay of Gangsterism in October 2023. I had a rough draft in 2022 that I tried to get funding for, but I couldn’t get it in Jeonju. And then when I showed Night Is Limpid, He Thought He Died came about, so that allowed me to work on something while I did that.

So obviously I was thinking about these situations there, too. Because I have all these other pictures in my head at the same time — they are all really deeply linked. I make this joke that if I have one in pre-production, one in production, and one in post-production at the same time, I can be in the past, present, and future at the same time, all braided together. And I think that’s another thing cinema can do for us in our relationship to time and our relationship to how we plan our production. I’m just trying to contradict myself — contradict, rethink what I’m doing each time just so I could move in a different direction.

ZL: In this movie, the main filmmaker, Clem, is being very attentive to previous criticisms of his work. There’s a great scene with a jury in which they’re arguing about the correct role of politics and representation in his movies. I’m curious if these are arguments you’re having with yourself in a dialectical process between you and the work. Or alternatively, is this more reflective of a kind of filmmaking community working through these issues? Or is it a combination of both?

IM: It’s all of those things in the sense that I wanted to make a movie of what it really feels like, at least for me, to make a picture in the year 2025, and what’s always important to me is to be very concrete in how the movies are made.

For example, you can do pitches in different countries, but also we could apply for grants here in Canada. And that’s very specific. So I wanna be very materialist and understand what that means when you’re making movies. For example, when I make stuff, I don’t have to worry about making a profit, so it allows me to experiment. I don’t have to worry about paying anyone back. So it’s these types of things I try to think about, but I thought the landscape of criticism and self-criticism are all really intriguing. And I love all those movies about making movies. Even the ones that aren’t about making movies end up being about making movies.

But also, yeah, obviously it’s very specific to where I live in Toronto, and I want to really think about what that landscape’s like because a lot of filmmakers don’t know where they live. They don’t know the concrete way they live, and especially, since we speak English, a lot of people in Canada confuse themselves for living in the United States or something.

And it’s a really crucial question of what cinema is and how you view your reality. If you live with a grant system, but you’re thinking like you’re an American picture maker, you might just be confused about where you are. And I want to make a picture of what it really feels like for me to live here and what the consequences of making movies here are and what responsibilities we have. And I think about it all the time because it’s not a theoretical question. By solving that, I figure out how to make the next picture. So I have to be very on point about how pictures are made here, the role of criticism, and what I can do with it.

That’s why there’s that one scene which was like, “Oh, I don’t try to read criticism, but I have to get someone to find pretty good ones so I could put them in the next grant.” Like it’s a very specific concrete production relation to it. But also, our producer, Kelley Dong, is also a film critic, so criticism is always alive when we’re thinking about what we’re doing and the relationship of what we’re doing to history.

ZL: There are a lot of conversations in this film about what it means to work with institutions that have historically funded filmmaking and the pitfalls and advantages that come with these places, like, say, universities or grant systems or the regular dirty money that that flows through the banks to organizations that normally fund bigger feature films. I’m curious as to how exactly this specific film got produced, and if you have any ideas about what a workable method of film production looks like going forward.

IM: This one we tried to pitch at Jeonju. We were invited to pitch Gangsterism when we were showing Night Is Limpid there. We didn’t get it, but I already started thinking about it quite deeply, so I had to put it on the back burner when I worked on He Thought He Died.

And then we applied for a council grant and we actually got it. But then there was a situation where we were working on He Thought He Died, and we had to wait for the institution to finish helping us. So I’m waiting on finishing that movie, and I’m trying to sit on this other money without spending it. [Laughs]

But I think part of it is really recognizing what it means to live in the digital era. I’ve been to too many sets where there’s way too many people on set as if it’s the 20th century and you need the script person and 10 ADs — something I don’t understand. If you look at the credits, I actually shoot it, I light it, I edit it, I write it, etc. Because that’s what you can do with digital. And Kelley does the sound recordings, the boom, and the color grading. That’s it. Once in a while we’ll have a PA, but that’s about it.

And I just feel like that’s a very digital question to me, but it also feels like early cinema, right? Just always recognizing you’re at the beginning. I think we’re always gonna be stranded at the beginning of making cinema in a positive way. Like in philosophy, every great philosopher thinks they’re somewhat at the beginning, even if it’s a new interpretation of someone else. But I think we’re beginning again and I think we have to just take that risk in thinking that way. Or like when Lenin says “beginning from beginning again,” I feel like to just say, “Okay, we’re doing something that, as much as we love our predecessors, they might not have been dealing with this.” We have a chance to take a risk.

For example, by doing it, I just got a little more experience in dealing with money. When I made Inventing the Future, it was a big shift from 88:88. So I had to really learn what it means to handle X amount of dollars and where to put it. We were joking with my friend Isaac who brought up that Francis Ford Coppola always said to spend a thousand dollars like it’s 10,000. I was like, “Oh, that’s not helping, I’m just going broke.” It’s a question of how you spend money — responsibly, but flagrantly. Because, you’re making movies, there’s no necessity for this to happen.

So you have to also trust yourself to spend this crazy amount for this ridiculous thing. I know when to do that. But even tiny things like, after making X amount of pictures, I know I don’t have to go to the U-Haul for that type of thing. I know another guy who lives out on this street who has a truck. By making picture after picture, you slowly learn how to cut down your costs on every little thing, and you learn what’s worth spending money on.

For example, I’ve been using the same camera since 2017, 2018. I used it for Inventing the Future. And the computer I’ve been editing on has been the same one since 2017. It’s been spitting out DCPs; it’s exhausted, probably. I just feel like all the focus on lens kits and getting the right Arriflex and all these other things are all paper tigers. Don’t get too worried thinking that makes it a real movie. I also think we don’t know what this will look like in the future. I disagree with this, but I remember someone said Inventing the Future was like La Chinoise if there’s better cameras. But obviously I’m an old man, so I think, “Oh, but that’s 35mm, right?”

But I feel like a different generation just doesn’t see it like that. So I just think you have to really lean into the equipment we do have access to, because I also feel like there’s no other time in human history I’d be allowed to make pictures the way I do.

And that’s why I always tell people, you have to buy your own equipment. Because you’ll give yourself permission to experiment. If you’re renting, you’re like, “Oh, I gotta make sure this makes money back. I don’t wanna throw the camera around because it’s not mine.” But if you own the camera, then you’re like, “Oh, let’s try that. Let’s try that. Let’s do this.” You won’t feel as pressured.

Beyond the equipment, work on your eye — look at some paintings, think about it. Technology forgets that cinema’s quite simple and we should know that. So there’s so much propaganda of how difficult it is to make a film, and we should know it’s a lot easier than you think. You just have to go and do it.

ZL: Like your previous films, here there are plenty of books spread out in various rooms, and characters are quoting them, and characters are bringing ideas from different topics. In this film, I’ve noticed that there’s an emphasis on the Pittsburgh School Hegelians, like Robert Brandom and Wilfrid Sellars are quoted a fair amount.

I’m curious about your particular journey coming to them, as well as how you feel that they fit into the narrative. Especially since it’s not just Hegel in general — we could play that game of Hegel, dialectics, Eisenstein with much of your work, but you’re very focused on the Pittsburgh School here.

IM: One of the things I’m interested in is that — for example, after 88:88, I wanted to think of institutions and not think of poverty. And after that, I thought with Inventing the Future the question of acceleration but also state politics. And that led me to really get into Kant and Hegel, and thinking with Hegel even more. I feel like A Spirit of Trust is just as big a reference point in Inventing the Future as Inventing the Future [Laughs]. People don’t talk about it, but Sellars is actually quoted in 88:88 a bit, too.

It’s been something I’ve been thinking about, but I feel like it’s because, as a filmmaker, I’m also very concerned with getting away from language. And as much as I love Sellers, let’s say, I do know in the end there’s an acceptance of the linguistic turn. And as a filmmaker, I want to be against it. But also, even Sellars himself says you can still think rationally, not necessarily with language, but he doesn’t explore that. But he does suggest it in one of those lectures on pre-Kantian themes. And so I feel like that was really huge for me.

But part of the break, honestly — and that’s why we named the Slovenian school as well in this relationship — was just because in 2023 with the genocide of the Palestinian people, I just felt that I don’t want to think with state politics anymore. I know that’s like my self-critique in relation to Inventing the Future, let’s say. And I have to not limit myself to that. Because when I think of thinkers who posit their idea of freedom from the state and who have to think it through the state, etc., I think of Hegel for sure. In my philosophical education, there’s always this idea that Hegel has this beautiful, perfect system and everything, and he always critiqued Schelling for doing his education in public. But I was always saying that artists always educate themselves in public. We should not be ashamed of that. And I always think people talk about unfinished work; but I know Capital wasn’t finished, and it still changed the world. I think we gotta be just more experimental. You can think systematically, but don’t get involved in the pure aesthetics of the system at risk of losing the activity of thinking. And yeah, with the concrete historical moment after October 7th, I just thought, “No, I don’t want to think with Hegel anymore, period.”

And then I got back into my mathematical ontology, which I moved away from for a bit. Because after 88:88, I wanted to just keep challenging myself. And also because as a filmmaker, I’m always against language and naturally predisposed against it. And I came up on Eisenstein, Godard and stuff like that, so I always had this big middle finger to language. So that’s why in Inventing the Future I wanted to challenge myself, to go all the way and go to Brandom and just play his game and work with dialogue scenes. I really want to think about language, really go into it. But fundamentally, I think with computational science and stuff in relation to this question with language is that it is a finite mathematics, right? That’s what got me back after the critique of Hegel and the state, because the state is — even for someone like Badiou — the state can be infinite. There’s not only one. There’s infinite infinities, right? So I don’t wanna reduce my thinking to only that first or second infinite since there are other, larger ones. So I went back to thinking with infinity again and went back to my old game of going against language.

But it was after this big fight, after this whole like proof-by-negation type of thing, I really went deep into language and language philosophers. There’s a lot more logic and ludics rather than mathematics in Inventing the Future. But ludics, even in its dynamism, is fundamentally finite too.

So going back to this more decisional thinking and infinity, it made me think, “Okay, now after doing the honest, intellectual work of thinking through the people I’m usually against in that game, I think I can return to some of my original intuitions regarding the cut and cinema as a site to think rationally — without mysticism, without language — but still rationally.”

So I came back to that, but also, especially with what’s going on in the world, I just thought of Fanon’s critique of Sartre and saying, “We were so moved by your existentialism, but when we started asserting ourselves, you were saying, ‘Oh, I have to be a good Hegelian here and say just wait your turn.’” And I just feel every time there’s some question regarding the shape of the world, there’s this question of “Can we wait? Is there a way to see the rose in the cross of the present?” I really want to intellectually fight against that in cinema. Because cinema isn’t language-based. And also because we saw the images of genocide, not necessarily the words. So I want to reconstruct my ontology again, back to the image, back to the cut, after this detour with language for a couple years. That was really key to me.

It’s kinda like my relationship to Hegel, too. It’s like if you have a crush on someone and you have to impress their spiritual in-laws. I obviously was really into Marx and all these other people, but I guess I have to also think about Hegel because he’s always there. [Laughs] It’s always been a fight. I feel like even the Maoist-era Cahiers was like, “Okay, Eisenstein’s like Marx, and then Griffith’s like Hegel,” and they’re always trying to think about this question as a nice metaphor. But actually, yeah, after the historical experience the last couple years, I just thought, “Okay, I wanna make an intellectual stand with cinema.”

I forgot who did it, but Hegel got really excited about an intellectual who said, “My ambition is to make philosophy speak German.” I feel like these types of ideas just reduce it back to language. I’m an old Platonist. I think it’s about things, not words. So I just feel the thing I’m interested in is the cut. And I think, whether it’s Pittsburgh or Slovenian, whether it’s Žižek or Pippin, they’re gonna just ventriloquize films to make it look like an allegory of The Phenomenology of Spirit.

I just feel like cinema can be more than that. I’m tired of watching movies just to find out a philosopher could explain it in another system from before cinema. I think cinema is a form of thought that cannot simply be reduced to that. And those feel like very weak ways of looking at cinema.

ZL: This movie has a jump-scare cut to Armond White’s Make Spielberg Great Again book. I think a lot of people will kinda perk up to that. Not only does it make an appearance, but there’s also a little montage poster with Mao and the flag of the Philippines.

IM: All the images, the frames and cuts, are like this, in that I try to push toward a compactness full of tension. That little frame is just one example. Because of course you see the Make Spielberg Great Again and you can think of American cinema’s relationship to the Philippines in the history of colonial power, but you also see the evolution of the Filipino flag, and at another point in the movie you see a movie ticket for Evolution of a Filipino Family. Part of the evolution of the flag is that you see KKK, which, together with the MAGA-invoking Armond White title, adds another tension. You can think of the Ku Klux Klan, but also the Kataastaasang Kagalanggalang na Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan — abbreviated to KKK — the revolutionary group against the Spanish Empire, but also as Katototohanan (truth), Kagandahan (beauty), and Kabutihan (goodness). And of course you can see the image of Mao twice: one divides into two vs. two fuse into one, and then how all these link and de-link together. Of course, I’ve been propagating the idea that the infinity κ can be thought with the Kuleshov effect as what is called a “witness,” and perhaps an infinity that is κ to the power of κ. κ times can defeat the cinema invented by Griffith that helped revive the KKK, and this image returns in the movie when the Kuleshov effect is deployed in relation to the crosscut. But this frame in Nico’s space is a nice metonym of how to see and listen to the sounds and images and frames and cuts in the movie. I wanted the movie to operate at this level of tension within and without.

But I think with the Armond White thing too — obviously he has his political views, let’s say. But I think a lot of people should still take him seriously in terms of thinking. I just feel like there’s too much dismissal of certain ideas about art. I feel like he was the only person who agreed with me that Drive My Car is a terrible movie. [Laughs] I will always defend taste, to not lower our ethical and aesthetic standards.

He’s the one who made me take A.I. more seriously as a kid, too. Even though he’s a conservative, when it became this question of whether Vertigo was better than Kane, he said a really healthy film culture would have Potemkin as number one. That’s what I mean. These are things I’m willing to defend in relation to thinking through cinema with him, let’s say.

I think with all the questions of race and politics in the movies, I thought he’s someone that’s like contemporary that I read. I have a very specific set of critics I like to read who are alive. I’ll still read Jonathan Rosenbaum; of course, I read Kelley Dong; I read Phil Coldiron; I read Craig Keller; and I read Armond White. And I make sure I check them out just because these are people I’ve read for quite a bit of my life. Once you’re committed, it’s too late. You have to read to the end, even if you disagree.

ZL: I think it’s synonymous with whenever leftists were recently saying that they need to be reading Carl Schmitt, the Nazi jurist, or when right-wing people are even saying that they have to contend with Deleuze. There’s something about reaching out and finding the extreme parts of culture and seeing what’s salvageable from that, because it’s gonna be stuff that, as an insular group, you might not be working out on your own.

IM: For sure. When I was trying to think about acceleration, I really went in on Spielberg for Inventing the Future. It’s a really important game to really think through every filmmaker at the level of contradiction.

I loved The Fabelmans, but I hated West Side Story. I always felt that Kael’s relationship to Bertolucci was like Armond White’s relationship to Spielberg. I feel like he really opened my eyes to what Spielberg’s actually doing, and that his writing on Amistad is very powerful.

ZL: Where a typical film might go to a crescendo during a big moment or, alternatively, keep the crescendo away from us in order to have some sort of big counterpoint, your movies will introduce a musical piece or even just a sound where you’re not expecting it, in terms of the traditional cinematic language. Have you found a method for this kind of sound editing that helps you establish the mood or idea you’re trying to hit? Or if there is some other kind of framework at play?

IM: In this one, I have a song that I made with my friends Alexandre Galmard and Kieran Daly. But I like to treat the music quite autonomously. And because I like the sort of monophonic quality of Kieran’s music in this one, I want to have this sort of purity of it just coming out. I want to enjoy that type of process.

But it also reminds me of the intermittency of the frame. I want to make it so that when we see new images that sometimes they match the beat and sometimes they don’t. It’s actually the way J. Dilla would time his beats, and instead of “boom-bap” it was like “boom,” then he puts a space there, and then “bap” comes later. But you already heard the “bap” that never appeared, and then it opens that up. But I treat Kuleshov like that too. You think it’s gonna be like face, object, face, object, face. And then if you change the rhythm of that, you’ll still see what you usually thought you would’ve seen mentally, but you could put someone else there and expand that shape, and that really interests me.

If you look at my earlier work in a superficial way, you might say the movies are cutting faster. But now I realize how to get that effect at a level of thought by just putting one flicker. Now that flicker just haunts you for the rest of the frame, rather than having “flicker-flicker.”

So now I’ll just put that one flicker there on the frame, then a different flicker. But now you’ve already infinitized it in your head, so I don’t have to always do that. It’s the same thing with the music, like putting down a sound and then gapping it, and then whether or not it comes back to you, its ghost is still there. And these are questions of infinity, of how we mentally picture it working. Is it pure repetition? Is it a loop? And by adding that break to it, that’s how you make it continue in your head. So that’s how I like to play with it.

ZL: Nearly every sequence of this film has a lot of dialogue, and then whenever we suddenly get to this seascape at the end, the dialogue cuts out and one of the only things we hear is the sea and maybe a bit of footsteps on the rocks. I’m curious where that is, since this film is very invested in its location. Additionally, what is it about the sea that kind of asks for this sort of silence?

IM: It’s just a little far out from where I live. And it relates back to the beginning of the movie with different colored water. And I just wanted to also get back to, after all this defense of cinema without language, just doing it.

By including words and dialogue doesn’t mean we’re siding with it, but it’s almost kinda prepping you after hearing all that to just give you back the images, the frames, the cuts, and the most minimal sound to think it through. That’s why I want to end it with that type of thing. Whether it’s gonna end with water or not, I just felt like I wanted to end it by remembering what it’s like to think in silence and look at images, and what type of associations one can make with the image and sounds. Obviously, that’s happening throughout the movie, but I feel like it’s further underlined when it’s when they’re given back the quiet.

Comments are closed.