Where is the line between genuine love and selfish devotion? That’s the question bubbling at the center of Dusty Mancinelli and Madeleine Sims-Fewer’s sophomore feature, Honey Bunch. The directing duo, now a couple, having gotten together while making revenge-thriller Violation, keep finding much to mine in the deep, thorny wickets of love. This time around, they find themselves exploring what it means to recommit to somebody; not just once, but as many times as necessary to make the relationship work.

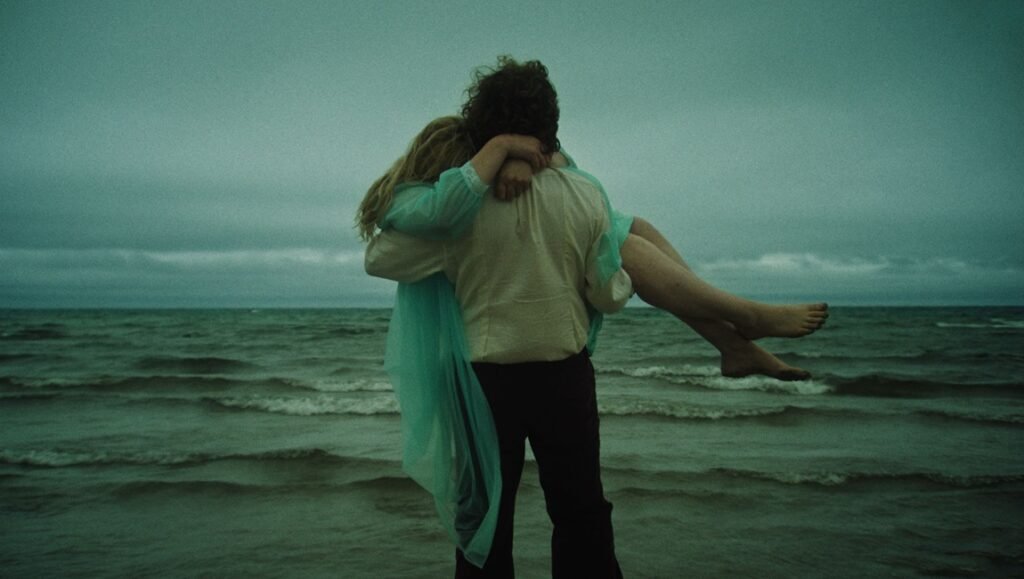

Set in the ‘70s, Honey Bunch follows Diana and Homer (Grace Glowicki and Ben Petrie), as the latter takes the former to a memory-care home after a violent car accident. Hoping to retrieve her memories through experimental treatments, the couple’s relationship is tested when Diana begins to remember some unseemly things about her marriage. After a father and daughter arrive (a terrific Jason Isaacs and India Brown), things get even murkier as it becomes apparent that Homer and the father know each other, and this might not be their first time at the facility.

For fans of Glowicki and Petrie, seeing them play relatively “normal” is a thrill. This is, of course, only superficial as twists reveal themselves, but watching Glowicki, particularly, in Honey Bunch is like seeing her in an entirely new light. An actress so fearless in muddying gender lines, and actually muddying herself with dirt, there’s a delight to her transition into playing such a classical leading woman: running around confused, trying to get to the bottom of it all, she’s not quite a scream queen, but something more akin to a ‘70s Euro-horror lead. This juxtaposition as it exists relative to how we’ve come to know Glowicki makes Honey Bunch’s creeping delights all the more eerie.

Ahead of its release, I sat down with Dusty Mancinelli and Madeleine Sims-Fewer to discuss the film, what it means to recommit, the genius of Grace Glowicki, and fighting yourself.

Brandon Streussnig: I’m so fascinated by how Honey Bunch plays with what it means to actually love someone. There’s such a fine line between actually loving someone for them and selfishly holding onto them for yourself. How did you land on that as one of the central themes?

Madeleine Sims-Fewer: I think that came up almost later, as I wouldn’t say that was the theme we began with. I would say that what we began with was this idea of what is devotion? What does it mean to really commit to someone? And I think we’re talking a lot about the way people see relationships right now. What I read in the zeitgeist about relationships is really transient.

Dusty Mancinelli: Also, this idea of a soulmate, that true love exists out there, that you just need to find the most compatible version of someone. I think we’ve come to realize that that’s a myth and that really what sustains a long-term relationship is recommitting yourself to a person in a relationship when you’re at the low point, the low inflection point; like, love ebbs and flows, and there are these valleys, and devotion really is recommitting in those moments. I think what you’re seeing is definitely there, that’s a part of the film. Homer’s journey throughout the course of the film is coming to the realization that his love was selfish, and he needs to learn that some of his actions were born out of his own desires.

MSF: I think sometimes there’s an idea that when you’re in a relationship, if you do something or if someone does something that is maybe a stupid mistake or morally questionable, that they’re a write-off and that’s it, and that it’s time to leave and find the perfect person. They did something wrong. So I think for me, the idea of selfishness is always going to be there in some way. And you are always striving to see beyond yourself and in a relationship to recognize when you’re being selfish and hopefully be less and less selfish, but you can’t help it. You’re always going to be selfish to some degree.

DM: There’s no perfect relationship or someone to love selflessly all the time. That’s just unattainable.

MSF: I think with parent and child relationships, too, that the relationship between Jason and India, we also wanted to show that this idea of the perfect parent-child relationship also doesn’t exist. There are many selfish things I’ve done toward my parents, and there are many selfish things they’ve done that have damaged my relationship with them, to. But I go on loving them.

BS: This is your second feature together. I know you became a couple while making Violation, and you’ve spoken on that a bit, but has that changed or informed how you make films together?

DM: Well, we met in 2015 at the TIFF Filmmakers Lab, and we became fast friends. So our friendship grew, and then we became collaborators. Then we worked together as friends for several years before even making our first feature. I think it was during lockdown and post-production. And it was really just: “We have to work on this movie. There’s lockdown. What are we going to do?” So we were spending all our time with each other, and it was inevitable that we would eventually become romantic with one another, but we had already built a healthy friendship and collaboration. So the transition from becoming romantic partners seemed pretty effortless and natural. It felt very organic. It happened when it happened. It wasn’t something that interfered in any way with our process.

MSF: No, but I think there was a certain amount of trepidation. There were romantic feelings that developed during Violation, and we didn’t know if we wanted to go there. But it was the first relationship, for me anyway, where I was friends with Dusty for a long time beforehand, and that brought a lot of thoughtfulness and depth.

DM: I think in all of our work, even when we were just friends collaborating, we’re approaching it from our own unique perspective. Madeleine as a woman, me as a man, and we’re trying to empathize and understand each other’s point of view. And so that hasn’t changed. That’s always going to be what makes our work our own exploration of trying to understand one another through these characters and the stories that we want to tell.

BS: Speaking of characters, you have two leads who are better at inhabiting them than anyone. I think we’re so used to seeing Grace and Ben portray weirdos or freaks that there was something so cool about seeing them, especially Grace, play someone so normal, so to speak. It’s a totally different lane for her. How did casting them come about?

DM: We’ve been big fans of Grace’s work for many years, but it was really this short film that Ben did called Her Friend Adam, which I think he made in 2015, where it’s incredibly naturalistic and grounded, and it’s a very different kind of performance from the rest of her work. So we knew she obviously had the ability to possess that. And, of course, she’s just a really terrific physical performer, and she really has this ability to physically transform in a really unique way.

MSF: She definitely had a harder time with the naturalism part in terms of, not her ability, but it was almost like, “Oh, are people going to understand this? Are people going to get this?” She leans into and very naturally plays characters who are very big and transformative. I think it was an interesting leap. We filmed all of that stuff, most of the stuff where she’s very, I don’t want to say natural because that’s not the right word…

DM: … No, but to use your word, Brandon, different. I mean, we shot chronologically for the most part. So all that fun stuff at the end of the movie came at the end of filming.

BS: They work so well off of each other, they always do. I mean, I love the scenes where they’re riffing with each other, trying to freak each other out with wilder and wilder examples of “Would you still love me if…” How much of that was improvised versus in the script?

MSF: It was all scripted apart from maybe one moment, the wolf dick moment.

DM: Oh yeah, there’s definitely a handful of hilarious lines because Grace and Ben are terrific improvisers. The wolf line for sure is Ben. I think there’s a line, I can’t remember if we wrote it…

MSF: The titties line was great. [laughs]

DM: That’s for sure Grace. There are just some really in-the-moment, where they’re taking something that’s scripted, and we’re like, “Go, go keep going.” And they’re building off of it. But we also had this amazing creative process where we wrote the script in conjunction with rehearsing with them so that we’d get feedback, see what was working, we’d try things out, and it would enter into the script. So by the time we went to shooting, a lot of exploration had already happened, [and] it wasn’t like they were performing for the first time.

[Spoilers for the last act of the film]

BS: I hope people see the film before reading this because this is obviously spoiler territory, but I have to ask: how did you choreograph Grace fighting herself? It’s such a fun fight scene.

DM: We pre-visualized the entire film working closely with our cinematographer, Adam Crosby. So we had detailed shot lists, we had floor plans. We worked with this terrific storyboard artist, David Mariachi, to visualize what it was going to look like, and then that still wasn’t enough. So then we worked with our visual effects supervisor to do animatics.

MSF: And the stunt coordinator.

DM: Yeah. So we had the animatics, which are basically little animations. Then, when we choreographed it with our stunt coordinator, Chris Marks, and put it up on its feet. We could see what angles were working and why they were working. That allowed us to be really meticulous about how we approached the actual logistical technical execution of it in terms of scheduling, because it’s really complicated when you’re dealing with hair, makeup, wardrobe, and costume changes. So, trying to figure out how to manage all of that was very challenging, but just required a ton of preparation. Once you have all that preparation, it allows you the kind of freedom on set to explore. Even though again, everything is highly choreographed, there’s a lot of freedom in finding the energy in the moment with the camera so that you’re really trying to create something that feels violent and engaging.

MSF: Grace really loved that, too. It was almost like choreographing a dance and learning steps. And then that gave a framework that she was able to just work off of emotionally. So it’s the same steps, but how do I make these same steps different every time? I think that was quite exciting for her to do.

Comments are closed.