Pacifiction

A favorite at Cannes for several years now, self-styled arthouse rockstar Albert Serra has had a dependable home th festival since his (narrative) debut feature Honor de Cavalleria back in 2006. That film, a minimalist reimagining of Don Quixote starring nonprofessional actors and rendered in surprisingly lush digital textures, established Serra’s filmmaking predilections immediately, his subsequent work holding fast to similar principles of style and theme. Founded on an obvious aesthetic contrast that subjects esteemed figures of the 17th/18th centuries to the unforgiving gaze of high-definition digital cinematography, Serra’s project thus far has been to detangle history from reality, reality from romanticism, and so forth. Seemingly a shallow well to draw so frequently from, he has spun quite a few variations on this fairly simple premise a few times over now to great success, most recently with 2019’s lush, hedonistic Liberté (which won Cannes’ Un Certain Regard sidebar that year), and, before that, Death of Louis XIV (also a Cannes selection, out of competition) and Story of My Death (top prize at Locarno in 2013 when the festival was still competitive). Clearly a director with significant clout on the European festival circuit, Serra has nevertheless been kept to sidebar selections and out of Cannes’ more classically-minded competition until this year, when his latest feature Pacifiction was announced as a last-minute addition to the lineup.

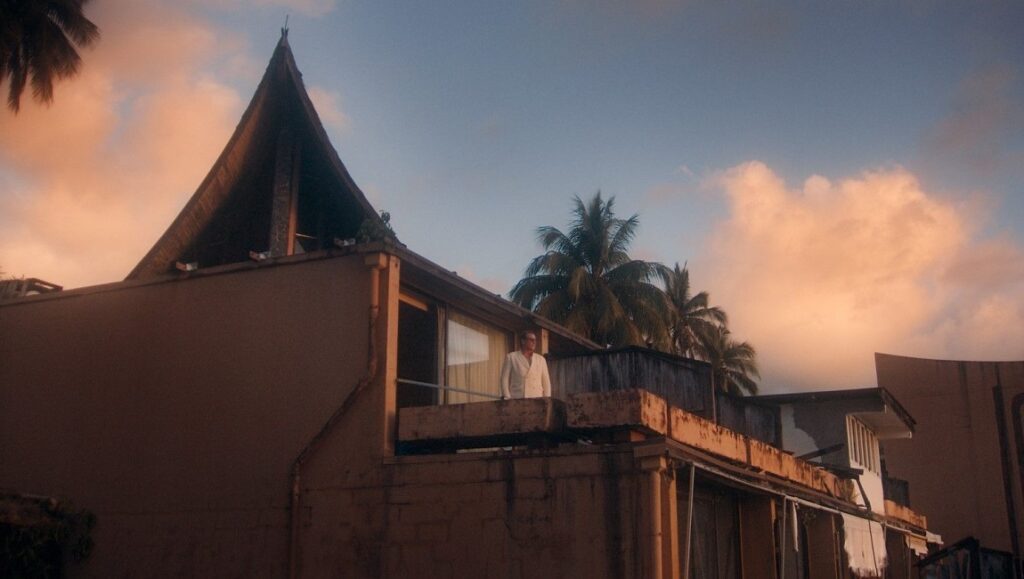

And indeed, as it currently stands, Pacifiction is the most comp-friendly title in Serra’s filmography, as well as an apparently dramatic break from the characteristics that have come to define it. Though not a total departure from his cinematic interests, Pacifiction at times comes off as a conscious realignment toward the values of the competition programmers, adopting a more conventional narrative structure and approach to staging, as well as swapping out his high contrast digital tableaux for a hazy 35mm look (though actually shot on three Canon Black Magic Pockets running simultaneously), framed in scope aspect ratio. But, what initially appears to be radical departure for this director quickly reveals itself to be of a piece with the logic that has previously dictated his filmmaking approach, this time using celluloid’s nostalgic, surreal qualities as a point of contrast to Pacifiction’s grim depiction of contemporary, bureaucratically-managed colonialism. Taking place in “Overseas country of France” French Polynesia, mostly on Tahiti, Pacifiction’s playful title alludes to both the film’s setting and its protagonist’s general role in the action.

The Piano Teacher’s Benoît Magimel leads the cast as the island’s Haut-Commissaire, a man of substantial political power sent to manage the populace on behalf of France and who fancies himself a benign actor, a pragmatist able to serve the interests of his native country without betraying those native to this overseas colony. Serra casts doubt on this ostensible balancing act early on, introducing the film’s looming conflicts in a meeting between the Haut-Commissaire and Tahitian representatives who express distress over their banning from a newly opened casino at the behest of a local religious leader, as well as a persistent rumor that the French government has secretly resumed nuclear testings on nearby islands despite vowing to discontinue the practice decades prior. Wielding the brutal power of tax dollars against religious leadership solves the casino issue rather efficiently, but the more alarming concerns of an encroaching military/nuclear threat are waved off as against the colonizer’s best interests. Still, the rumor gains traction as an ominous submarine is spotted lurking the shores at night, and as Pacifiction’s methodically paced 165-minute runtime spills out, the film’s focus shifts to the tension between the Haut-Commissaire and his self-enforced obliviousness, his attentions torn between production details at a scuzzy Lola-esque nightclub, and the numerous sinister foreign agents suddenly inserting themselves in local business.

Like the bulk of Serra’s output, Pacifiction is superficially readable; as in, one could likely guess the outcome and general thematic revelations in store just by glancing over its plot synopsis. Yet, the overtness of Serra’s metaphor isn’t really an issue as it’s rarely been previously, forgoing writerly coyness in favor of a more emotionally resonant sensory experience. Entrusting frequent cinematographer Artur Tort to shepherd in this vision, Pacifiction adheres to a cool, magenta color palette (presumably inspired by the aforementioned Lola, probably Querelle too) with strict consistency, casting the players in a soothing rosy sheen, unbalanced by a dread-inducing score and rumbling soundscape. Magimel excels in a reserved, cagey performance (straddling Ben Gazzara in Killing of a Chinese Bookie and Saint Jack) serving as avatar for the contemporary liberal middle manager type — charismatic, politically savvy, and very desperate to maintain a faux status quo. In keeping with the recent bout of smart, stylish French cinema (though hailing from Catalonia, Serra’s recent films have been very Franco-centric) contextualizing the building fury with the failings of the Western liberal state (see, for example, Zombi Child, which makes similar use of a magenta font color, and last year’s France), Pacifiction is just about as good as any of those. Even if some of his voice is more obscured than in features past, this latest effort still reflects a pretty clean aesthetic reorientation that suggests we’ve yet to see the full breadth of Serra’s design.

Writer: M.G. Mailloux

The Fabric of the Human Body

Véréna Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor’s De Humani Corporis Fabrica (The Fabric of the Human Body) is a veritable encyclopedia of the human form, a visual compendium of organic processes, functions, and systems. Taking its title from a 16th-century book of anatomy by Andreas Vaselius, the film comprises footage filmed in various French hospitals over a period of five or so years. After opening with the sight of a guard dog prowling through the basement corridors of a hospital, we cycle through footage that covers an impressive range of contrasts: scenes of geriatric patients wandering through hospital halls, a C-section birth sequence, prostate surgeries, and eye operations. These are of course thematically motivated, linked either to various aspects of organic functioning or the physical operations of the hospital. As in Leviathan (2012), though, a film that would not have been possible without GoPro cameras, much of the surface interest in De Humani derives from seeing footage captured by non-standard cameras, allowing us to image regions of the body that were once impossible to see.

There’s a natural comparison to be made between De Humani and Stan Brakhage’s The Act of Seeing With One’s Own Eyes (1971), which, as Jonathan Rosenbaum writes, is “one of the most direct confrontations with death ever recorded.” This is often taken as a materialist thesis that we are nothing but physical matter, just aggregates of bodily systems and processes; and Paravel and Castiang-Taylor may be seen as affirming the very same in De Humani. But as the film goes on, what comes through most vividly is the opaqueness of the world, the idea that no matter what technology one uses, there is a real sense in which life is not something that can be imaged. The sight of a capsule propelled through the hospital’s pneumatic tube system recalls nothing less than the “Beyond the Infinite” sequence in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and indeed, De Humani offers a journey into inner space to match Kubrick’s odyssey to outer space. And despite their obvious differences, they arrive at virtually the same point, at the sense that organic existence — symbolized by Space Odyssey’s Star Child, or De Humani’s delivery sequence — contains enigmas that no scientific explanation can ever account for. What De Humani thus demonstrates is that the effort to go “beyond the infinite” is not a simple matter of location, not a question of “inside” or “outside,” but has to do, ultimately, with that mystery we call life.

Writer: Lawrence Garcia

Magdala

In recent years, Damien Manivel seems to have become a latter-day example of the French auteur hiding in plain sight. Like such figures as Paul Vecchiali, F. J. Ossang, and Jean-Charles Fitoussi, Manivel has existed at the periphery of the French industry, making films his own way and following his own star. His 2016 film The Park debuted at Cannes that year, and his last film, Isadora’s Children, attracted attention after being picked up by MUBI for online distribution. In light of this, one might reasonably expect that by this point, he’d be appearing in the Quinzaine, if not Un Certain Regard. But it’s to the credit of Cannes’ newest sidebar fest, ACID, that they chose to screen Manivel’s latest as their opening night feature.

Magdala is a meditative film, proffering only the broadest outline of narrative information. That’s partly because Manivel is operating in the mythic register. This film observes the agonized final days on earth of Mary Magdalene, played by veteran actress Elsa Wolliaston in a bracingly physical performance. For much of the film, Magdala is hunched over and hobbling through a wooded thicket beside a stream, bearing herself along with a walking stick and soothing her parched lips with rainwater dropping off of leaves. At various moments, her survivalist resolve breaks down, and she curls up in anguish as she mourns for the lover she has, in a sense, outlived, but who of course is ever-present. In one particularly striking moment, Wolliaston uses the walking stick to draw a rough portrait of Jesus in the mud-caked on a rock, and she has a compulsion to bind twigs together with blades of grass in the form of the cross.

In Filmmaker Magazine, Blake Williams noted that Magdala partakes of a somewhat familiar “slow cinema” sensibility, at times suggesting the work of Lisando Alonso and especially Albert Serra. The former’s La libertad and the latter’s Roi Soleil are certainly appropriate points of comparison, but I also observed a focus on ritual and portraiture that recalls the para-narrative works of Philippe Grandrieux. It should be noted, however, that Magdala does not quite match the mastery of form displayed by those filmmakers. The film is attractively shot by Mathieu Gaudet, and the images often lend Wolliaston’s skin a verdant tone, as if she were less a human being than an extension of the surrounding landscape which, under the circumstances, we’re asked to recognize as God’s creation.

But when it comes to the cinema of longueurs, editing is paramount. Manivel assembled Magdala himself, and at times there is a lack of clear motivation for one image following another. Also, although the final act may be preordained in some respect, it is protracted without achieving the desired rhythm or mood. Magdala almost signals this sense by ending on a strikingly literal note, a move very much at odds with the atmospheric film that we’ve just watched. Perhaps the most successful tonal shift arrives mid-film, when Magdalena recalls her younger self (Olga Mouak) in a tender moment with Christ (Saphir Shraga). This interlude, which provides Magdalene with an interiority that she lacks for most of the film, hints at the richer, more complex film Manivel might have made. Nevertheless, Magdala is a wholly unique cinematic statement, the kind that one encounters less and less at the big international festivals.

Writer: Michael Sicinski

Domingo and the Mist

The eponymous protagonist of Domingo and The Mist lives on a dilapidated dairy farm, high in the hilly rainforests of Costa Rica. He spends his days tending to his cows and occasionally trekking down the mountain to visit his middle-aged daughter. He spends his nights drinking clear liquor from an unmarked bottle with two or three “neighbors” who live a mile or so down the one dirt road in the area. The rest of the time he spends around his property, speaking to his deceased wife, who manifests as a serpentine, apparently sentient cloud of mist.

Ostensibly, the central drama of Domingo and The Mist concerns a highway, to be built over the land where Domingo and his neighbors still live. Developers in a distant office somewhere have decided that this tract of verdant rainforest is the most convenient path between some unnamed city and some other one, and have sent representatives first to bribe and then to threaten the last few holdouts in the area, Domingo included. Two helmeted, gun-wielding men begin to appear each night, driving up and down the otherwise deserted mountain road. Domingo, who believes his wife’s spirit can only visit him on the foggy mountain peak where she once lived, refuses every bribe and threat put before him, even as his drinking buddies start to disappear, or turn up dead under suspicious circumstances.

Though we spend much of the film following Domingo between just a handful of locations, many of them are lush, leafy rainforest paths, which would quickly blur together were it not for filmmaker Ariel Escalante Meza’s sharp sense of geography and sequencing. These boundless hills and valleys begin to feel enclosed, even claustrophobic, as Domingo sees fewer and fewer recourses for keeping his life and land intact. This sense of enclosure also gives the film a fable-like quality which helps sell its rather simple David-and-Goliath morality. Though it contains several frank depictions of predatory and coercive tactics used by real governments and corporations to dehumanize and displace rural populations, Domingo and The Mist is not overly concerned with real estate development, redlining, or global capitalism. Rather, as the drama unfolds, the helmeted men become something of a specter, a symbol of Domingo’s increasingly futile quest to hold on to his wife’s spirit or memory.

On this note, the film remains largely agnostic as to whether or not Domingo’s wife really appears in the mist. His daughter believes he’s either senile or perhaps drunk. Yet in several long, lovely shots, the mist certainly does seem to move with a sense of agency, twisting itself into a closed room or delicately winding its way up a narrow forest trail. Although we don’t see or hear her during the times when Domingo seems to see and hear her, the wife does get a few gnomic, voiceover monologues throughout the film, speaking as though she were Gaia. These more mystical, lyrical passages lend an appropriate gravity to Domingo’s plight, giving a supernatural sense of purpose to what would otherwise be a story about a very stubborn old man. How each viewer interprets this poetic, possibly otherworldly dimension of the film will likely inform their reception to its elliptical, ambiguous ending. While Domingo and The Mist offers few concrete resolutions across its 90-minute runtime, it nevertheless achieves a difficult balancing act of reality and allegory, thanks in no small part to Meza’s careful and confident handling of his own, admittedly somewhat light script.

Writer: Mark Cutler

Corsage

When Empress Elizabeth visits a mental asylum — the sort of place in 1878 where men are institutionalized for mental disorders and women for adultery — she encounters a caged woman in the corner of the room. The woman writhes in the chains that bind her to her bed and screams in a fit. Later, when Elizabeth returns to the place, wearing the same violet dress she did before, she encounters the same woman, only that now she is asleep, at peace — for a moment — with her captivity. The meaning is obvious, the parallel to Elizabeth’s royal life easy to draw. Watching Corsage, the new film from Marie Kreutzer, one fears that the old, sturdy period piece metaphors — the cages and the corsets from which the film takes its title — have been exhausted. Even the striking, potentially potent image of the Empress staring out the window in a room that is much too small for her, her head almost bursting through the ceiling like a giantess in a doll’s house, is reduced by familiarity.

With all these images, there is no need for investigation or thought past the point of recognition: she is a woman fenced in and restricted. The symbols mean what they always have and what they likely always will. Likewise, the anachronism of the pop soundtrack, including diegetic performance, is at this point old hat, neither challenging nor poignant, although Kreutzer does find room for fantastical, purposeful anachronism eventually. The ways filmmakers tell stories about royal women, particularly those in period settings, have started to calcify. Corsage is, in places, a victim of this staleness, but it sports a fantastic Vicky Krieps as the caustic and complicated Austrian Empress, so it’s good anyway.

Set in 1878 after Elizabeth has turned 40, the age at which most of her female subjects are expected to die, the film finds the Empress, a practiced fainter who avoids public visitation when she can, obsessed with her age and image. In effort to lose weight, the royal will try anything; she’s not eating and she’s working out. She fences with her husband — could any movie with Vicky Krieps wielding a sword be bad? — before trading verbal barbs with him. There are experimental bath treatments and, eventually, drugs. So obsessed with her appearance is the Empress that she at one point orders her portrait artist to copy her existing portraits but account for her new, improved complexion. That all of this behavior, including the mean streak she brings to bear against her servants, could be chalked up to her oppressive environment and the sexually charged rumors about her and several men is familiar, yes, but believable enough that it compels nonetheless. Besides, it’s not as if she cuts a simplistic figure or is particularly in need of rescue. She is warm towards her children, even as they are as critical of her as they are their father, her young daughter at one point raising some particularly precocious fuss about smoking. Through all of this Krieps gives a restrained, compelling performance that keeps the character from being a one-note woman in trouble.

Aside from being Elizabeth’s 40th birthday, the year 1878 allows Kreutzer to place her at the birth of cinema; 1878 was also the start of Eadweard Muybridge’s experiments with motion pictures. Elizabeth, who hates being photographed and veils her face in public, finds joy in being filmed where she can move around without the camera picking up what she’s saying. In a silent, black-and-white sequence, we watch Krieps give a performance so unlike that of the film’s reality. She’s unrestrained, ecstatic, and clearly shouting, an act that never happens in a film of such controlled volume that the latter could maybe benefit from more of this exuberance.In reality, Elizabeth would be assassinated 20 years later, but Kreutzer contrives a trick to allow for an escape, a final bit of fantasy that closes out Corsage on a bittersweetly high note.

Writer: Chris Mello

Under the Fig Trees

An example of the laziness rife in digital filmmaking, Erige Sehiri’s Under the Fig Trees employs a haphazard handheld cinematography that echoes the immediacy of prosumerism (or, the increased involvement of consumers in production processes), with a color grade drastically alien to the environs Sehiri seems intent on subsuming her characters within. The film observes the casual dynamics of laborers on an orchard in northwest Tunisia; a demographic collection whose interaction unfurls some ideological insight into their gendered, religious, and generational rifts. The grand issue, however, is that these conversations — elicited from either moments of mundanity or contentious frictions between opposing perspectives — offer little in the way of characterization; in fact, the dialogue only works to suffuse these individuals with straw. Uncomplicated discourses engender anonymity. Perhaps the most heated moment in the film stems from such aimless diatribe, which surrounds the issue of being able to, quote, “fix him.” If this moment weren’t peremptorily contextualized within a disagreement on conservative ideologies, it might play as parodic.

The worst offender, however, beyond the screenwriterly pontification of the interpersonal, is the completely avoidable sludge of log-level coloration. Greenery is gray; skin and light too. This textureless blot of what can only be imagined as beautiful landscapes is the quaff of vitality. There is no life in the image, its barrenness further accentuated by meandering shot-reverse-shot sequences, its estrangement provided by the handheld camera (not just of space, but also of its inhabitants). Frankly, it boggles the mind as to why this has to be a film. (Such an aggressive quandary is perhaps reductive, purposefully obfuscating the fact that time-based media is certainly more reproducible than most other mediums today, but regardless…). With such unyielding care placed in the formal qualities of the work, and with seemingly more attentiveness fostered in the textual faculties of the piece, based solely on dialogue, why could this not be a short story? Why must there be images? The images here, in fact, only hinder the potential for evocation. What could have been impressionistic understandings of landscape, affective dynamics imagined, instead becomes a dull and literal rendition of unfinished photorealism.

Titled Under the Fig Trees (or “Under the Tree,” as a direct translation from its Arabic title), the film is composed of dialogues taking place under, well, a collection of trees. There might be something respectable in its unembellished nature, if not ultimately for a coda that offers a romantically tinged basking wherein the cast sings together until overwritten by a melancholic musical score that exhausts. Suggested here is a kind of connective tissue between these people and their schisms. And if it’s only this commingling of contrivances and characters, each of whom could be aptly discerned as conjectural analogues, and built toward this gesture of shared experience, then perhaps this writer has missed something. Perhaps this uncharitable interpretation has overlooked a centrifugal lattice upon which these characters interact and are interwoven. This might, indeed, be so, but the eyes that watch the work don’t lie, and in taking in Under the Fig Trees’ near monochromatic totality, it’s hard to find much to confront here other than a deluge of triviality.

Writer: Zachary Goldkind

Comments are closed.