Fairly or not, Manfred Eicher’s ECM Records has long been saddled with a reputation for producing airy and cavernous Euro-jazz, best exemplified by Keith Jarrett’s mid-70s solo piano excursions and the Scandinavian folk / Gregorian chant mashups of tenor/soprano saxist Jan Garbarek. Certainly one needn’t dig deep into the label’s lesser releases from the 1980s and 1990s to support such a slightly dismissive report. And yet much like Blue Note’s brief championing of Cecil Taylor and Ornette Coleman in the midst of dropping juke joint soul jazz LPs on a backbeat-hungry public, ECM’s back catalog supports a wide roster of forward-looking musicians, from one-time Ayler apostle Garbarek himself to recent dense offerings from Downtown fixture Tim Berne’s Snakeoil project. And long before the famed/heckled ECM aesthetic settled into place, the Munich-based label was home to any number of fiery avant-gardists, including the Circle ensemble, a quartet roughly centered around pianist Chick Corea featuring Dave Holland on bass and Barry Altschul on drums, with post-New Thing Chicagoan flashpoint Anthony Braxton supplying a grab bag of reeds. Corea would rarely again approach such frenzied territory. But for Holland the Wolverhampton-born bassist, Circle would prove a jumping-off point for the rest of the decade — less arch than his work for the Spontaneous Music Ensemble, less plugged-in than his groundbreaking contributions to electric-era Miles Davis.

For fans of American free saxophone, the album is an endless treat, with two of the decade’s premier avant-leaning hornmen helpfully split into opposing channels for easy distinguishing, unencumbered by any chordal intrusions.

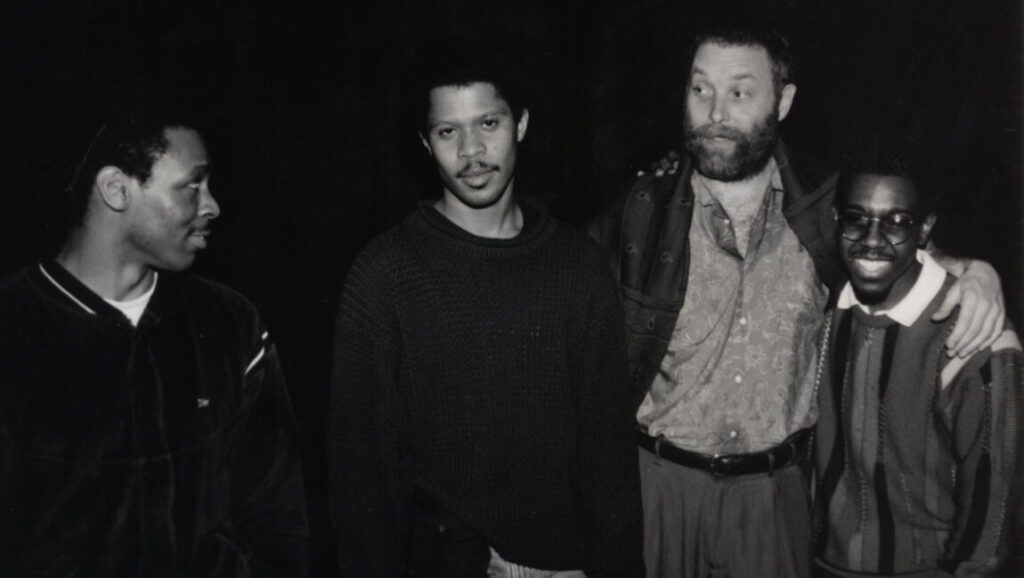

With Corea’s piano (and accompanying harmonic baggage) jettisoned, Circle morphed into the David Holland Quartet, adding the reedwork of inside/outside pioneer Sam Rivers to the lineup. Like Holland, Rivers had put in time with Miles, albeit briefly and contentiously, a pre-Wayne Shorter fill-in for George Coleman. Holland knew how he wanted these six simple compositions to sound, settling upon the dual horn lineup after a bit of tinkering. In fact, early versions of the songs making up Conference of the Birds were trotted out during live performances featuring the Brecker Brothers and guitarist Ralph Towner — the mind boggles. For fans of American free saxophone, the album is an endless treat, with two of the decade’s premier avant-leaning hornmen helpfully split into opposing channels for easy distinguishing, unencumbered by any chordal intrusions. The method was simple. Short, almost whimsical melody statements, punctuated by open-ended improvisation, with the severe modernism of “Now Here (Nowhere)” and the rattle/shake whirr of “Q & A” surrounded by breakneck swing (“See-Saw”) and a title cut as lovely as “Naima” yet unmoored from the strictures of Western composition. That number, with its gentle marimba and purring flutes, pointed the way towards ECM’s future cash cow, i.e., post-sixties spirituality morphing into tasteful global fusion, Garbarek soaring atop the Hilliard Ensemble. Yet “Conference of the Birds” avoids any hint of exotica (Holland himself has noted the title refers to mornings outside his London flat, not the 12th century Persian poem). And while the twin saxophones ignite the Ornette At the Golden Circle Stockholm stop/start dynamics of “Interception,” they also float joyfully along the twisting melody statement of “Four Winds,” free to screech and honk when the spirit moves them, yet always responsive to the steady swinging pulse anchoring the quartet. And for this, one must credit the generous yet steady (and deep-toned) leader’s right hand. It was to prove a high point — for Holland, for ECM, and for 70s jazz.

Part of Kicking the Canon – The Album Canon.

Comments are closed.