The albums that defined the past year were projects that subverted typical genre norms and traditionalist views, making themselves hard to rigidly categorize in the process. With foreign influencers making waves across across a smattering of Billboard hit singles (more on one of the biggest from this year a little bit later) and the dominance of the ever-growing “playlist” mentality — cramming in as many wide-ranging music styles for maximum streams, i.e. Migos’ Culture II and Drake’s Scorpion — the push for the blurring of these once explicit classifications has only heightened in the past 12 months. On our list alone, we have three different hip-hop albums that openly embraced discussions of mental health; a Japanese noise pop release with flavors of industrial rock; two different country albums by women that flew in the face of stereotypical gender norms; and the return of a rap legend after a near-decade in release purgatory (aka Birdman’s clutches). Even the songs selected here tend to find ways to shatter musical expectations, with the inclusion of a near six-minute long SoundCloud odyssey; a bold, basey proclamation of gender identity; an avant-garde rock anthem about playing pretend; and the emotional capstone to one of the most audacious release projects in recent memory. If our lists seem expansive in how wide-ranging they are, that’s simply a reflection of the changing times we live in — or, more appropriately, the global sphere of a shared music listening experience that’s become an integral part of the critical discourse. Paul Attard

SONGS

10. An indie-pop experiment that embraces volatility, “Only Acting” is the fullest realization yet of UK trio Kero Kero Bonito’s singular genre alchemy. Lead singer Sarah Midori Perry’s vocals — pitched perfectly between earnestness and detachment — navigate the inner life of a stage performer grappling with the ephemeral nature of her art: “Now I know I shouldn’t get comfy on the set / Every time it all comes down when we end.” Her melancholy is interrupted by the the song’s ebullient pop-punk hook, a jarring stylistic shift for the keyboard-and-synth combo, hitting so hard that it leaves the entire song coming apart at the seams. “You should be able to feel a performance with your whole body and soul,” Perry intones, as a squalling noise breakdown blooms around her. The backing instrumentation cleverly enhances this instability by using familiar sonic elements even as a breakaway guitar solo and momentary bridge set the stage for a key-change fakeout; and then, a rug-pulling denouement of reverse-looped vocals and eerily spare synths. It’s as though the song dissociates from itself, echoing the compartmentalization espoused by Perry’s narrator, its structural integrity sacrificed to the band’s staking out of new sounds. Not since Satoshi Kon’s anime classic Perfect Blue has the boundary between idol pop and pure madness been so spectacularly obliterated. Alex Engquist

9. Lil Uzi Vert’s breathless “New Patek” is a veritable masterpiece of that abstract genre known as ‘Soundcloud rap.’ The song constantly re-contextualizes itself through variations on a theme, reframing — variously — its phraseology, intonation, and flow, and set to, of all things, its producer Dolanbeat’s interpolation of the opening theme of an an anime from 2015. As Genius’s take on the song’s structure points out, unsurprisingly, there’s a chorus and a hook — but there are also repeating lyrical sections, and these sections can crop up, almost at random, in the chorus or as part of the hook. To simplify: After just a single play, due to its repetition and variation, one may well experience every shade of emotion that could possibly be gleaned from the bar “Franck Muller made me proud of my wrist.” While most of Uzi’s contemporaries in the SoundCloud/former SoundCloud rap game concern themselves with two-minute songs that emphasize vocal swagger and charisma, Uzi had to “switch it up one time just like [he] had to switch his phone,” and make a six-minute, stream-of-consciousness rant about…everything. “New Patek” weaves brags, negs, sexual incidents, Naruto name-drops, “real talk,” and a lot of designer watch references into one sonic tapestry, skyrocketing anticipation for Uzi’s much-teased sophomore album, Eternal Atake. While lines about other MCs being nothing but a “clone” and “stealing his flow” might be directed at Rich the Kid — Uzi’s most vocal beefer — they could also just be taking aim at the rap game as a whole, or some other up-and-comer who might want to claim themselves as the hottest in the game. And while circuitous, taunting lyricism may run the show, the MVP of “New Patek” is its vaporwave-y elevator music instrumental, which provides a platform for Uzi’s vocal fireworks and bolsters the sheer potential in a rapper’s voice — the expressions of timbre, intonation, and flow. After flexing all these abilities, over nearly six minutes, the song fades out; but it does so just as Uzi begins the chorus again, reminding us that the song never really ends — this is just all we get for now. Joe Biglin

8. Some things never seem to change: The 1975 make self-important, distended, and overwrought albums. But give this year’s A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships at least some credit; its title is comprised of roughly a third as many words as that of their 2016 album (look it up). And while the verbosity and outsized ambitions of this band have proven unwieldy on each of their full-lengths, they happen to be perfectly suited to the parameters of an individuated pop song. The highlight of (goddammit, fine) I Like It When You Sleep, For You Are So Beautiful Yet So Unaware of It is the bright synth-pop of “Ugh!,” which jams almost 400 words into the limited space between its surging riffs and bubblegum rhythms, a compression that, musically and emotionally, frontman Matt Healy’s lovelorn narrator specifically laments: “The kick won’t last for long / But the song only lasts three minutes.” This year’s “Love It If We Made It” isn’t so rushed, nor so internalized; it opens with a slow, shimmering pulse, raising concern that this might be another of the band’s place-holding ambient pieces. But suddenly, the track erupts, with Healy’s dive-bombing vocal careening in even before the sharp crash of the kick, before the ambient shimmer of the backdrop starbursts into a kaleidoscope of swooning strings and arpeggiating synths. Summoning a veritable stadium-rock maelstrom, The 1975 mean to not only collect all the disparate influences that make up their hybridized pop, but also to take stock of the various forces that define this moment in pop culture. That may sound just as self-important and facile as making an album about How The Internet Generation Loves, but that ever-important sense of compression comes into play again here. Verses filled-to-bursting with allusions to Trump and war and Kanye and Jesus and Lil Peep and suffocating black men and failed modernity approach a cynicism overload until, at almost exactly the midway point, the song upends itself, finding a simultaneous catharsis and ecstasy in the wail of rock guitars, angelically cooed vocals, and an irresistibly danceable beat. The whole thing’s over in four minutes, and, as the meandering hour of this track’s host album proves, some things never seem to change: The 1975 remains a great singles band. Sam C. Mac

7. What’s the proper taxonomy for a song like “I Like It,” the mid-album banger that turned out to be the most enduring hit on Cardi B’s blockbusting Invasion of Privacy? One possible categorization is roots music — because more than any other Cardi jam, “I Like It” feels like a celebration of where she comes from. Over a boom-bap beat that lifts its boogaloo exuberance from an old Pete Rodriguez anthem, Cardi celebrates her Brooklyn origins, her Dominican and Trinidadian heritage, and the surprising allegiance to old-school hip-hop that provides her entire album with its sure-footed sense of craftsmanship. It’s an uproarious and balmy block-party tune that announced itself as the Song of the Summer before winter had even thawed — but even as she looks back, Cardi’s also eying the way forward. Enter the ubiquitous Colombian singer J Balvin and Puerto Rican rapper Bad Bunny, both of whom send sparks flying in their colorful cameos. Their collegial features are welcome, but Cardi is always the center of her own universe, and her bars on “I Like It” show off her versatile flow, her proficiency with rhythm, and — of course — the outsized, braggadocious personality that made her a star in the first place. Josh Hurst

6. Where once the world of rap music emboldened ‘the connoisseur,’ nowadays, it’s a world that tends to champion ‘the influencer’ above anyone else. This isn’t to say that old is better than new, but that each element of a contemporary rap song (and in turn, of an album or a mixtape) feels heavily scrutinized by artists and A&R types alike for the sake of social media marketability. No one has understood this better than the man we refer to as Drake, an artist who practically speaks in hashtags and adheres to a creative process that looks just a little bit like a Silicon Valley incubator. As such, it’s only fitting that The Tastemaker King blessed us with “Nice for What,” the one true Song of the Summer of 2018, and also the definitive Influencer Anthem for Generation Thot. As with most Drake tracks from the past few years, “Nice for What” is an act of musical colonization — in a sense, Champagne Papi’s very own Louisiana Purchase. That said, the track’s appropriation of New Orleans bounce is almost humble, suggesting some remorse over the artist’s years of sonic vampirism. Sure, Drake can’t help but defensively remind us of his mentor-relationship with the Big Easy’s own Lil Wayne (“Lil Weezyana shit”), but he otherwise acquits himself by positioning bounce icon Big Freedia as the song’s MC and affording N.O. producer BlaqNmilD some Top 40 recognition. Drizzy and Co. build off of the nostalgic vocals of Lauryn Hill’s “Ex-Factor,” with that track’s barbed interrogation of a lackluster paramour lending credibility to a song that champions female autonomy (via the perspective of a male artist). One could view this as a cheat; after all, Drake has never sold himself as a guy with a Laissez-faire approach to dating. But disingenuous or not, the song is an irresistible curve doctrine, a call to put that wishlist link in your bio. It’s “Sugar Babies of the World Unite.” M.G. Mailloux

5. Easily forgotten amidst the gnarled, but brilliant, detritus of Oil of Every Pearl’s Un-Insides is the pop music savviness that made SOPHIE a forward-thinking producer in the first place; those times when she made straight-ahead pop instead of disguising her music through sleight-of-hand, concealing knottier conceptual gambits. “Immaterial” is the closest the producer comes on the new album to excavating that sound, to marrying the titanic squelch and beatless ephemerality of one of the year’s best albums with the punchy, delectable club beats of her earlier work. And the end result is a weightless, gossamer banger that succeeds, partially, by the virtues of a meditation on what constitutes gender and identity, but which also relies on the energy of its gorgeous, glassy synths. What makes SOPHIE’s music so endlessly compelling is the tendency to flaunt pressing questions about who she is and what forms her individuality, while also embracing a less vexing option: dance in the face of existential misery. On the one hand, an artist’s work can gain much from grappling with ideas of purpose, meaning, and the whole shebang; on the other, shaking ass until there’s no ass left to shake is never a bad choice. “Immaterial” is special because it seamlessly combines these outlooks, flying in the face of gendered conformity and being a banger to boot. Because, at the end of the day, what’s the point of deconstructing club music, searching for some basic human truths, if you’re not in it for the clubbing itself? Will Rivitz

4. A track like “Everything” has more in common with Nasir producer Kanye West’s “New Slaves” then it does with the old Nas; it speaks to how systematic, racialized abuse has not disappeared but rather has become even more normalized: “Listen vultures, I’ve been shackled by Western culture / You convinced all of my people to live off of emotion.” The song establishes Nasir’s thematic through-line, both in the manner that Nas sees systematic abuse being perpetuated and how he recognizes this abuse as a now-invisible line of segregation. Nas’s distrust of institutions can get muddled — the Old Nas returns for an anti-immunization lyric at one point (“Takin’ his first immunization shots, but this is great / The child’s introduction to suffering and pain“) — but the rapper’s status as one of the great poets and storytellers of hip-hop is unchanged. And there is poetry to a line that sees systematic abuse in a continuum with the first time a child experiences pain — it’s a profound juxtaposition, actually, suggesting that abuse has become so normalized that it’s a natural and inevitable experience. This is also why “Everything,” with its chorus that declares the need for a complete reclamation of the world, feels so necessary. Neil Bahadur

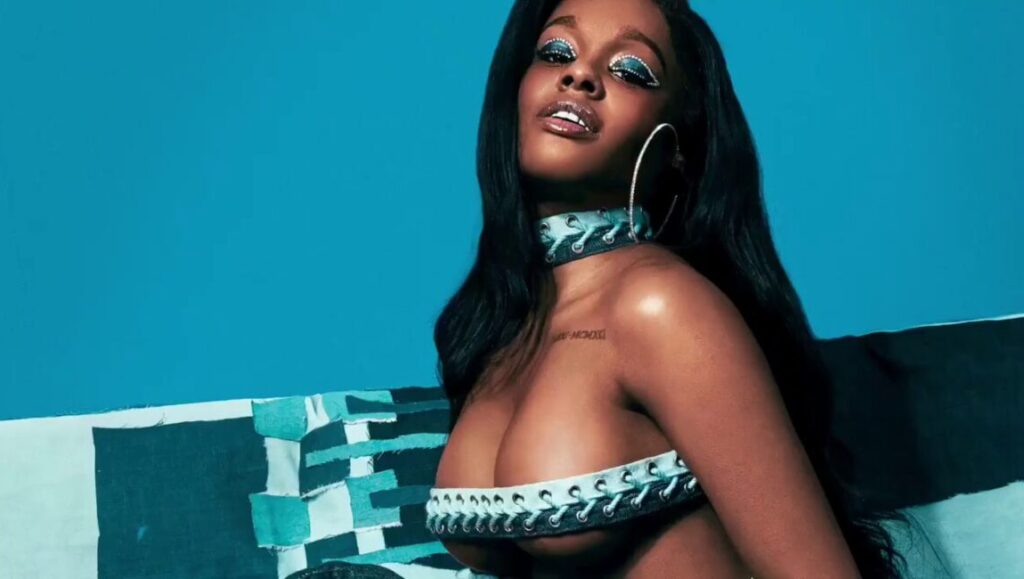

3. This was a busy year for Azealia Banks. Aside from falling out with various celebrities on social media, the singer/rapper found time to court her gay fanbase: first by pioneering a cosmetic sex product aimed at gay consumers, and then by naming her comeback single “Anna Wintour” (after the popular fashion icon) and proclaiming it “the gay wedding anthem of 2018.” While the song’s ferocity may make it an unsuitable accompaniment to any conventional nuptials, Banks has still made one of the best tracks of the year with “Anna Wintour,” a rebellious house banger that celebrates her renewed self-image with typically fierce brio. Serving as the lead single of her (still unreleased) second album, Fantasea II: The Second Wave, the track is a rip-roaring assault on the eardrums and drips with newfound confidence, hope, and energy. Despite plenty of knocks, Banks has never publicly come across as anything but assured, yet some of this song’s lyrics suggest she has emerged from a distinct period of self-doubt. “Then you show me, now I believe / Diamonds and dreams come true for girls like me,” she emphasizes, hinting at personal revelations about faith and love. While there are references to lambs and saviors to illuminate the role of Christianity in her rejuvenation, “Anna Wintour” mostly feels like a declaration that Banks doesn’t need anyone to complete her. “I’ll be better off alone. I’ll walk at my own pace” she announces, with the independence of a woman comfortable in her own skin — but who knows she has plenty of battles ahead. Calum Reed

2. The most common readings of Robyn’s output inevitably make use of the word “fembot,” a pejorative that posits her as some kind of Ex Machina experiment who it just so happens can dance and write a mean pop hook. It’s a reductive and too easy way to engage with songs like “Indestructible” and “Dancing on My Own,” which slay or bang or slap or whatever other repurposed violent verb du jour, but which also boast a profound understanding of complex emotions like grief and loneliness and resilience. With “Honey,” Robyn looks to be rid of those robot comparisons for good; she actually downplays the sugary-food-as-sex metaphor of the title — which, if anything does, proves her songwriting chops — and, instead, creates a song that impresses for its empathy. She may sing, “No, you’re not gonna get what you need,” but she does so over one of her most sumptuous, exquisite tracks. Jonathan O’Keefe

1. “So, I guess it’s only right that I do my favorite song too then, huh?” Kanye West said in the closing minutes of his Kids See Ghosts set at Camp Flognaw, right before launching into a rendition of “Ghost Town.” One can’t blame West for holding the song in such high esteem; after all, his year long antagonization of fans and media alike left him in a spot where neither party was interested in expressing open approval of his music. Nevertheless, reactions to the track remained generous. One could ascribe this vague trend to any number of things — most obvious being the fact that it’s as good as any of Kanye’s great anthems, and in turn one of his best songs. But while there’s no denying its accomplished, sweeping melody, nor much reason to expect anything less from Yeezy at this point, “Ghost Town” is as much a supreme pop song as it is an assertion of solidarity between artist and audience, and ultimately serves as an attempt at an explanation that will never quite satisfy, but still manages to reassure. The narrative of the song threads itself suggestively through an austerely constructed gauntlet of verses, eventually building out into a mythic tale where the internalized pain of Kanye West and the pain of the world at large become indistinguishable. “Ghost Town” captures the greyness of the last few years, effectively evoking that lingering feeling that things didn’t work as they were meant to. The song is built around a refrain of the word “someday,” a quirky fixation for a song that feels so contemporaneous; but it’s a sense of dissatisfaction and restlessness that makes it one of the defining songs of 2018 (a year in which no one really wanted to live). And because Kanye’s never been a defeatist, he concludes on a perversely empowering note, an act of celebratory self-harm capable of reinvigorating humanity. No doubt this message is a bit…rough-hewn. But through it, Kanye appeals to our shared history. He’s imperfect, but he knows that we all are as well. M.G.M.

ALBUMS

10. Lil Wayne’s Tha Carter V; or, Make Wayne Great Again. The 36-year-old Louisiana-born rapper had been in a slump of mediocrity since the first months of the Obama administration. Who was expecting a comeback so out of nowhere, with no advance signs of improvement? What changed? One of the first things Wayne skeptics will notice is the energy: Weezy sounds engaged and stimulated — and completely reinvigorated — on early banger “Dedicate,” which includes the kind of freewheeling, gymnastic wordplay he made his reputation on 20 years ago. And on the dramatic “Can’t Be Broken,” he charges through reflective monologues with more precision and fluency than he’s been capable of in years. (Indeed, his performances wow on a technical level throughout.) Wayne also seems to have rediscovered the ear for pop hooks that left him around the time of No Ceilings: “Mess” is his catchiest song since “Lollipop,” and “Famous” has the infectious grandeur of a bona fide chart-topper. And he at last seems happy to follow his own interests rather than those of the radio, or the demands of a crowd. Nowhere does this attitude-change prove more fruitful — and moving — than on the pair of tracks that bookend Tha Carter V: hard-hitting voicemail intro “I Love You Dwayne” and tuneful, Sampha-sampling closer “Let It All Work Out,” on which Wayne opens up about a suicide attempt he’d previously claimed was an accident. Tha Carter V finds Wayne more comfortable with himself, more trusting of his instincts, and disinterested in chasing trends. Calum Marsh

9. Multi-faceted, one-of-a-kind Japanese artist Haru Nemuri has been writing and performing her own songs and lyrics since she started her career — and she somehow manages to one-up herself in both respects on Haru to Shura. While opener “Make More Noise of You” does little besides set-up the generally more rock-focused sound of the album, as compared to Nemuri’s previous releases, second track “Narashite” does much to dispel fears that Haru to Shura may be a one-note release. Kicking off with a bouncy electric guitar figure, Nemuri keeps pace by giving one of her most captivating vocal performances; even as a self-described “poetry rapper,” she isn’t necessarily known for her ‘flow,’ but the lead-up to the chorus on this song is perhaps her most confident and memorable delivery to date. From a production perspective, “Nineteen” feels like a leveled-up version of the music Nemuri made early in her career, but with the droning synth lines that have since come to characterize her work. By drawing on a consistent aesthetic vocabulary, Nemuri continues to form connections between everything that she releases, in ways that are concise and easily recognizable, from referring to herself as the “saishuu heiki” (or, ultimate weapon), to incorporating abstract, introspective monologues on love and rock and roll. While Haru to Shura is ultimately less varied than some of her other releases, it is by far Nemuri’s most consistent and large-scale album to date, proving that her range extends far beyond the indie, pared-down sound that she’s heretofore relied on — and allowing her a measure of international acclaim that Japanese indie artists rarely enjoy. Taylor Murnane

8. There will come a day when Kanye West fails to translate the controversy and messiness surrounding an album release into a compelling and singular body of work. Ye isn’t that: All the poorly phrased opinions on slavery and the MAGA hats and the Twitter rants and Candace Owens support in the world aren’t going to make these seven songs in just under 24 minutes any less impressive for the way they articulate his own experience of mental health, his varying methods of coping with it, and its painful collateral damage. Kanye’s specific disorder is Bipolar (a word scrawled across Ye’s cover) and that’s important in terms of interpreting Kanye’s approach to his lyrics and his music. On opener “I Thought About Killing You,” Kanye not only draws on the double meaning of “ye” through purposefully slippery pronoun use (“Today I seriously thought about killing you”), but also uses distinct production choices to split the song in two. In the first part, a placid, medicated-sounding Kanye drones on emotionlessly over a spectral, oscillating vocal sample, looped like words caught in the back of the throat, while in the latter, a surly and aggressive Kanye bark-raps over percussive synths and guttural screams. It’s during the brief section between these two parts, though, that Kanye sounds most lucid, buoyant, and like himself: his flow locks in with the pulse of the bass, and his words express a desire for connection with the world outside of his own head. This is something like the “event horizon” moment of Kanye’s psychology, whereas most of Ye delves into exploring the effects of the void (or, “the sunken place,” as Kanye calls it). The licentious “All Mine” features Jeremih and his protege Ant Clemons singing in a creepy falsetto about being “crazy in the medulla oblongata,” while closer “Violent Crimes” starts as a sweet lullaby for five-year-old North West, but morphs into a panic-stricken screed of fears about fatherhood. “The lie is wearin’ off,” warns 070 Shake, and in filters an unflattering paternal anxiety. But this is partly why Ye works: As with other recent Kanye albums, there’s a willingness to be unpolished, to destabilize, to provoke, and to challenge perceptions — all as a means to humanization. What makes Ye different is that here Kanye is processing his personal flaws in relation to his own psychological imbalance, candidly recounting the strain that his off-meds TMZ meltdown put on his marriage (“Wouldn’t Leave”) and admitting “I scare myself sometimes” in practically the same breath as he boasts that Bipolar is his “super power!” (“Yikes”). That last line has been received as another troubling Kanye controversy, but largely that’s because people tend to forget that the Ye of his music speaks for himself (in part, of course, because he’s put so much effort into his populist message this year). And if Kanye’s merely striving to derive some measure of personal strength from his malady, only the most ableist would deny him that self-empowerment. SCM

7. Though still a far cry from her punk and country roots, Hell-On finds Neko Case returning to the knotty American Gothic aesthetic that best suits her considerable gifts. Case’s narratives often avoid traditional linear structures, hinging on oblique memories (“My Uncle’s Navy”), character sketches (“Winnie”), and a worldview that verges on cynicism (“Bad Luck”). Still, her writing here is some of the most forceful of her career, and in support of her most fully-realized persona: That of a woman who’s been irrevocably harmed by the world but soldiers on with a focused and righteous rage. Case has never been one to suffer fools, but on this album’s best songs she’s particularly salty: Both the title track (“You’ll not be my master / You’re barely my guest”) and “Last Lion of Albion” (“You’ll feel extinction / When you see your face on their money”) exude palpable and focused rage. That Case is in fine voice throughout is a given; and her lush production, which draws most heavily from folk and chamber pop, is perfectly matched to songs that feel at once timeless and out-of-time. JK

6. Just a single listen to “Azucar,” one of the highlights of Earl Sweatshirt’s Some Rap Songs, should held illuminate what makes this album so masterful. In a brisk 86 seconds, Earl mentions family issues, the many vices he’s relied on to cope with his demons, and a tight-knit group of friends who’ve helped him stay afloat. Odd Future-affiliated Sage Elsesser’s production features a lively sample of The Main Ingredient’s cover of Stevie Wonder’s “Girl Blue,” and has as much of a stake in the song’s sense of disorientation as does Earl’s slurred delivery. As the sample is looped ad infinitum, one feels the dreadful dissonance that Earl must experience on the daily — his inability to be happy, despite sensing that he should be. The chop from “Girl Blue” consequently couldn’t be more apt: “Your happiness is due / But still they last, there in your past / Events that make you blue.” The samples, Earl’s flows, and the short tracks on Some Rap Songs bring to mind other albums, from Madvillain’s Madvillainy to Count Bass D’s Dwight Spitz to MIKE’s May God Bless Your Hustle. But none accomplish the same feat that this album does: Through 15 tracks in 24 minutes, Earl captures the bleak but true-to-life mental state of depression. Joshua Minsoo Kim

5. The ladies of Pistol Annies continue an exceptional streak with their latest album, Interstate Gospel, which opens with an interlude that well introduces the theme of this set: “This interstate gospel is saving my soul.” All three ladies have gone through major changes since their last album together (Lambert with her divorce from Blake Shelton, Monroe with the birth of her first child, and Presley, newly pregnant with her second). Naturally, the songs here all find the Annies reflecting on the choices women make: Those of “Best Years of My Life” settle for less, while those of “Milkman” lament their mothers’ tameness. Never do these sentiments feel treacly or preachy, as in many a modern country narrative; instead they always feel authentic, even if the production occasionally drowns-out the stunningly expressive vocals of the three ladies (“Stop Drop and Roll One” being most culpable). What never fails the Pistol Annies is the relatable imagery found in each of their songs, which is especially true of “Masterpiece,” a song written and sung by Lambert, and which includes the lyrics “Baby, we were just a masterpiece” and “Once you’ve been framed you can’t get out” — followed by the striking challenge of “Who’s brave enough to take it down?” The song could be applied to the dissolution of any perfect-seeming relationship, though it would be hard to make a case that it isn’t about Lambert’s high profile marriage to Shelton. The song also offers some insight into Lambert’s thoughts on her relationship — did she stay for the sake of keeping up appearances, or was there more? Not that hers, nor any of these ladies’ personal lives are any of our business — but damn if their experiences haven’t provided them with some terrific new material to draw from. Stephen Eisserman

4. Julia Holter’s mosaic-like Aviary is often anxiety-inducing in its sheer intensity. Holter knowingly keeps her audience at a distance, challenging them emotionally and intellectually with knotty compositions and only occasionally indulging moments of pathos, before switching things up again. Take “Chaitius,” an 8-minute epic that begins as a Renaissance troubadour tune, with an increasingly dense string arrangement that gives way to a wavering vocal collage, before dissolving into a free-jazz bass line and underscoring that with a dadaist vocal sample interpolation that sounds as if the dead are trying to speak through the music. This is the first half of one song (Holter ultimately builds to an all-too-brief moment of rocking-the-fuck-out before letting the track fizzle into nothing) on an album where each individual track seems to invent its aesthetic as it goes. If there’s any point of comparison for this album, it might be Joanna Newsom’s work: Both artists have indulged years of experimenting with avant-garde and pop sensibilities, Holter maintaining trappings of chamber pop, Newsom of folk; both artists’ works reveal secrets over time and with patience. Don’t let that be a deterrent. While the noisy sound collage of Holter’s debut, Tragedy, crops up in, say, the blaring bagpipes (which sound like kazoos?) of “Everyday Is an Emergency,” that track is followed by a soothing, resonant piano ballad. This is an album whose story is the sound, and whose sound is story — while Holter puts the onus on her audience to interpret her lyrics, which may or may not be empty of meaning (the fake Latin words of “Vocal Simul” in particular). Nevertheless, at least some kind of subjective narrative can be found here — between the frantic psychobilly freakout of “Les Jeux to You,” the silly jack-in-the-box leitmotif of “I Shall Love 2,” the languid countermelodies played by the trio of instruments on “Words I Heard,” or the triumphant, life-affirming repetition of “I shall love!” (from “I Shall Love 1”). The main joy here, in fact, comes from a sense of discovery, of exploring Aviary as if it were a dense network of caves. Traverse through these corridors at a comfortable pace, and you’ll hopefully see the light. JB

3. If Ariana Grande’s Sweetener was the feel-good pop project of the (late-ish) summer, built on the catharsis of a newfound love (at the time…), then Honey presents itself as a melancholy antithesis — one appropriately dropped in the middle of fall. Robyn’s eighth album streamlines emotional distress into a series of mini-narratives that ruminate on the subjects of loss, endurance, and recovery — sometimes simultaneously. The music itself assists plenty, with tracks like opener “Missing U” telegraphing Robyn’s feelings through a whirlwind of glittering synthesizers, while the volatile run from “Human Being” to “Send to Robin Immediately” serves as a stinging recoil from the boldness of the first track. But it’s the lyrics here that actually carry the most weight, drawing significance from Robyn’s personal life (the last four years saw the death of her longtime collaborator, Christian Falk, and the dissolution of her engagement to filmmaker Max Vitali), while locating a universal accessibility in heartbreak. For Robyn, music can work to represent an all-encompassing process of healing — a suture that doesn’t always demand specific identification. Honey’s closer, though, repeats a personal mantra (“Never gonna be brokenhearted / Ever again”), using the progression of a pounding kick to build intensity, and it conveys an emphatic expression of confidence. Like most things in life, grief and happiness comprise a cycle, with no finality. But for now, at least, Robyn’s effort to overcome that reality registers its own renewing power. PA

2. Kacey Musgraves has always set her sights on that which might lie beyond the borders drawn around her. While 2015’s Pageant Material searched for narratives outside of the modern country community that inspired 2013’s Same Trailer, Different Park, this year’s Golden Hour sounds removed from any previously inhabited sphere. The album’s departure from Musgraves’ foundations is most obvious in its production; its sound is decadent, with disco and vocoder experiments entering the fray, and its atmosphere uncompromisingly vast, approximating the feel of a mirage in a Southwestern desert. Musgraves makes changes to her songwriting as well, transporting her songs into a more spiritual realm, and indulging in manipulations of time: minutes get stretched out into a span of days in “Lonely Weekend”; that ellipsis in the chorus of “Space Cowboy” feels like an eternity. The album’s highs, though, come from Musgraves’ sense of cosmic awe: “Oh, What a World” strives to do nothing less than sum up the Earth’s immense beauty, its scale and its shimmer, and “Slow Burn” assigns great emotional weight to the seemingly mundane, to fleeting moments. Life, as observed by Musgraves, is simultaneously run-of-the mill and very much one of a kind; the world that surrounds us both overwhelming in its expansiveness and abundantly rich in small detail. Ryo Miyauchi

1. Kids See Ghosts’ eponymously-titled debut is built on self-actualization: Kid Cudi and Kanye West both interrogate their mental health and navigate the resultant dialectical morass. Thematically, vocally, and lyrically harmonious, this pairing feels like an organic, fully-realized fusion rather than a one-off. Cudi’s more earnest sentiments supplement Kanye’s braggadocious confessionalism, and each performer softens the other’s edges (Cudi’s soppiness, Kanye’s abrasive cynicism). Rather than antagonizing any sense of parity, the two rappers work to support each other’s realization of struggle; a rhapsody in two distinct voices. On album highpoint “Reborn,” they put voice to concomitant but divergent understandings of their truths, of their pursuits of acceptance amidst the expressions of brokenness and alienation that permeate the record: Cudi rhythmically croons a celebration of mindful intentionality and self-regenesis (“I had my issues, ain’t that much I could do / But, peace is something that starts with me”), while Kanye, in his signature halting flow, seeks inspiration and control in the often self-wrought chaos of a life that, fittingly, he can’t extricate from its public context (“What a awesome thing, engulfed in shame / I want all the rain, I want all the pain / I want all the smoke, I want all the blame”). Sonically, Kanye follows a similar course of fêted mania on Kids See Ghosts; his production builds orchestral layers of fuzzed strings and distorted drums across the album’s concise 27 minutes, his chopped samples predictably socko on cuts like “4th Dimension” and “Freeee (Ghost Town Pt. 2),” while detouring into jaunty anthemics (the aforementioned “Reborn”) and deeply felt, gospel-tinged vulnerability (closer “Cudi Montage”). This is an album of mutual artistic elevation, a synthesis of the cerebral and the sincere, one that seeks to accord understanding over explanation and one which, all respect to Ye, more artistically and heartfeltly embodies a Kanye-coined aphorism: “I hate being Bipolar it’s awesome.” Luke Gorham

Comments are closed.