Chilean filmmaker Pablo Larraín’s darkly compelling second film, Tony Manero, is a sadistic character study set in 1978 Santiago. It’s unrelenting and often unpleasant to sit through; in a sense the more solemn cousin of another film from this year, Jodi Hill’s Observe and Report. Both bear the unmistakable echoes of 1976’s Taxi Driver, by examining the behaviors of mentally altered and compulsively violent individuals. The central characters in both films are prone to erupt in bouts of rage, but, while the violence in Hill’s film is usually caused by his character’s short temper, these outbursts in Tony Manero are both dispassionate and mechanical, triggered less by emotion than by necessity. Hill chose the template of a comedy in which to conduct his stinging social critique; Larraín’s is a stark realistic drama, closer tonally to Martin Scorsese’s classic and pervaded by a gloominess befitting its time and location.

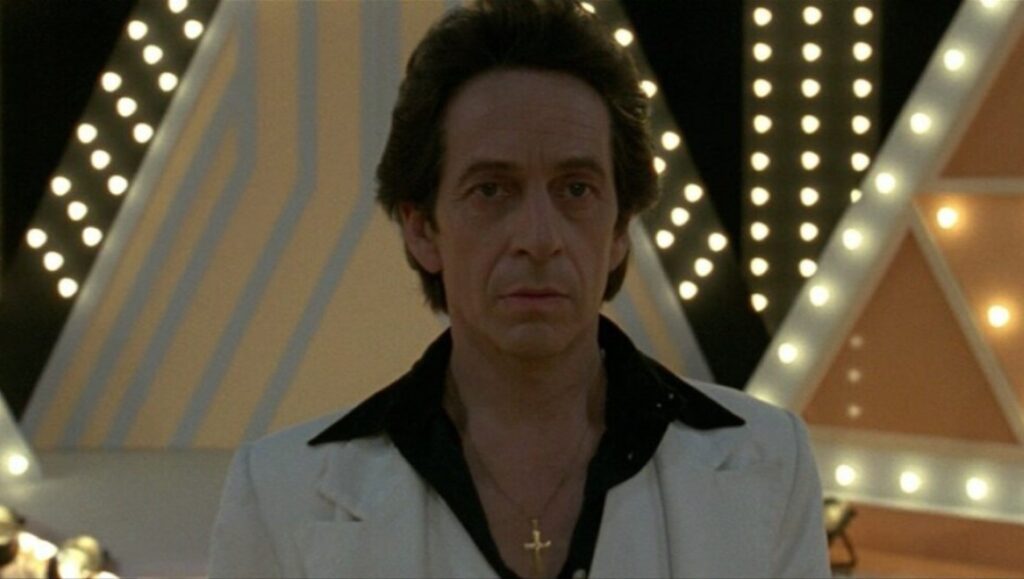

This establishes Tony Manero as a political commentary, capturing a totalitarian Chile strangled by the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet, while its people yearn for escape and act with the innate desperation of a cat clawing its way out of a paper bag. The protagonist in Tony Manero is this idea taken to its extreme ends. We cringe at the sight of him beating the life out of his unsuspecting victims, often with his bare hands, but through this depravity Larraín clearly says something: he comments on the influence of an environment fraught with poverty, corruption and moral decay. The man is Raul, weathered, middle-aged and of average build. He’s played by Alfredo Castro, who delivers one of the year’s best and most haunted performances, communicating a cavernous emptiness through gaping blue eyes and muted expression. His lover diagnoses him as “dead inside,” and this is mostly true, excepting when he sits in front of the silver screen, basking in the mirrorballs and bellbottoms of John Badham’s 1977 disco-era classic, Saturday Night Fever; he lights up even more when he takes to the dance floor, emulating the choreography of John Travolta’s Tony Manero with obsessive precision. Saturday Night Fever, and specifically the glamorous life of its star (the very embodiment of masculine energy and authority), offers escapist entertainment for some, but for a man of Raul’s obvious mental instability and discontentedness, the fantasy is too desirable to accept its unreality. Raul’s life is filled with filth; he shares a tiny one-bedroom apartment above a seedy bar with his girlfriend, her temptingly coy daughter, and the daughter’s political activist boyfriend, thus forming something of a pseudo family. Together, they all dance on the bar’s rotting stage, and Raul scolds anyone who deviates from his idol’s specific routines. He adopts every element of Tony Manero’s persona as his own, practicing not only his dancing but mimicking his posture, mood and the exact dialogue from the film. Seeing Saturday Night Fever on the big screen (or, as he calls it, Le Fever) becomes almost a religious experience — a concept Larraín alludes to by showing us one sequence from Badham’s film in which John Travolta, bare chested and from a low angle, ritualistically slips on his golden crucifix. Raul weeps.

This is all done in preparation for a television competition; we see Raul auditioning – on the wrong day — in the film’s opening sequence. The competition seeks to find the “Chilean Tony Manero,” and because of it Raul becomes obsessed with his impersonation. To those who stand in the way of this determined and irrational man: watch out. Larraín pulls no punches in depicting his lurid character throughout Tony Manero. Raul kills an elderly woman in her home in order to steal a color TV, bashes a man’s head in who offers him less than the TV is worth and defecates on a competitor’s white suit. Larraín launches a political critique via this provocative character study and suggests an animalistic compulsion awakened within Raul as nearly every obstacle he faces is overcome with remorseless brutal violence.

The film is meant to be volatile and void of redemption, but Larraín does perhaps take things too far at times; the scene in which Raul smears feces all over his rival’s clothing is less psychologically revealing and more shocking for the sake of it — not to mention plain nauseating. Other scenes are equally repellent, the more so because the film is so devoid of feeling. In this sense, Tony Manero can be compared to Carlos Reygadas’ divisive 2006 Cannes entry Battle in Heaven, which similarly targets its country’s — in this case Mexico — political institutions, deteriorating moral values, religious complacency, and class tensions, alluding to these hot button issues through an overweight man’s sexual and, in-turn, social inadequacy. The difference is that Reygadas employs a rigorous formalist aesthetic and deliberate narrative structure — the film begins and ends with audacious sequences of oral sex. Larraín, in contrast, crafts a film less stylized and more realistic, with gritty hand-held camera work. Larraín does, however, allow for one aesthetic manipulation; his camera’s focus fades in and out almost erratically, but conveying Raul’s hazy state of consciousness and his blurred moral judgment.

The filmmaker also employs one surrealistic flourish: the film’s real-time pace is briefly interrupted by a visualization of Raul’s internal emptiness, as he stares vacantly at the screen. This technique’s singular application makes it all the more devastating. By an incremental difference, Reygadas’ approach seems more successful than Larraín’s, if only because the emotional distance Reygadas instigates in Battle is more excusable, since focus is always on the craft, and since his hand is deliberately noticeable throughout. In contrast, Larraín’s decision to hew closely to realism is slightly undermined by his disallowing any measurable emotional response from his character — especially during Raul’s more violent episodes. It’s perhaps too extreme to suggest that a man can commit such heinous acts without any visible remorse, and Larraín toes that line a bit too often. Raul may be numb to his world, but he’s not comfortably numb, and yet there’s never any discernible sign of his unrest. This could have stifled Castro’s performance, but the actor is so good that he often transcends the stoical nature of his character and communicates far more than what’s on the page. In any case, Larraín should be praised for conducting a political critique in so bold and provocative a way. Tony Manero is challenging, if not exactly redeeming, and it illuminates through provocation, functioning on a variety of levels: as a character study; as an examination of a society’s relationship with celebrity; and as confident, assured cinema.

Comments are closed.