Scary notion: what if YouTube, with its streaming transmissions of home-movie inanity and fleeting flashes of sign o’ the times import, was our first and only source of pure, uncut, unfiltered reality? What if those little snippets of amateur verité — the camera confessions, the clowning around, the sudden tragedies and horrific accidents caught on tape and looped for eternity — now offered a more honest, probing glimpse into human nature than what we can glean with our raw peepers, each and every day, in our homes and on the streets? Is digital video the ultimate lie detector, a multimedia prism through which the real world reveals itself? Does truth run 30 fields per second? Answer to all of the above: thankfully, blessedly, a resounding “probably not.” YouTube is no more a purveyor of Absolute Truth — no less a garish corruption of it either — than the reality TV rubbish filling primo network timeslots every season. Still, to an impressionable young mind, one sick on the spirit-corrosive artifice of our culture at large, that mere illusion of truth can be plenty attractive.

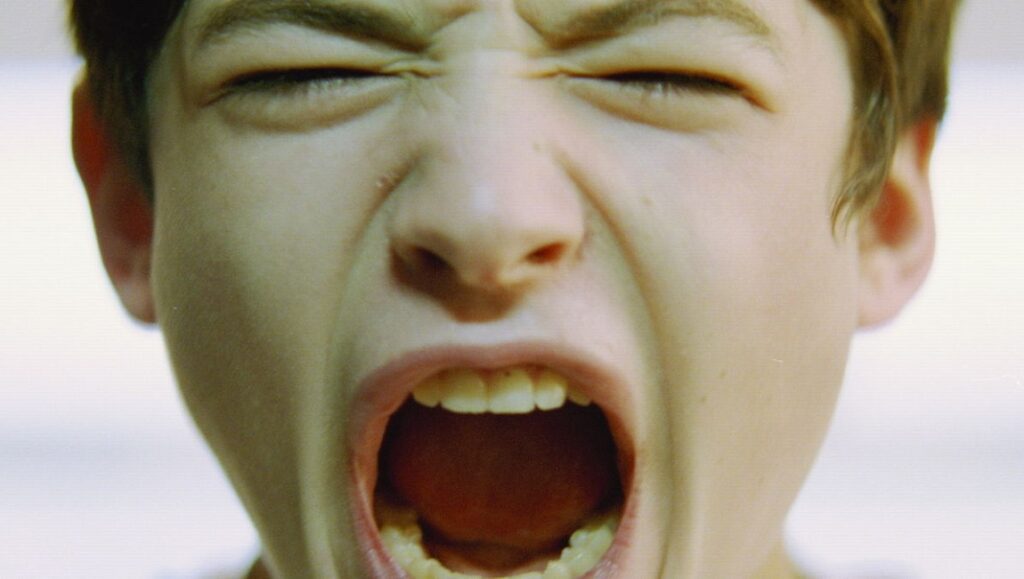

In Antonio Campos’s Afterschool, sixteen-year-old Robert (Ezra Miller), pale and painfully shy, locked in his own private prison of awkward adolescence, skulks the halls of his posh prep school like a ghost. He doesn’t fit in here. Hell, he barely speaks the social language. His popular peers, preoccupied as they are with blossoming hormones and mind-altering highs, regard him with an ever-shifting mixture of scorn, pity and indifference. So lonely and detached is this teenage pariah that his only solace comes from scouring the Internet, getting lost in video vignettes, and in the regular doses of humor and horror that lie at his very fingertips. A glum and bombastic dissertation on our 21st-century, viral-video-obsessed age, Afterschool begins with one of Robert’s ADD-influenced web sessions, a montage that toggles between innocuous curiosities (giggling infants, a kitten playing piano) and more troubling bursts of sex and violence (the Sadam execution, a particularly aggressive and puerile porno site).

Then, in the first of several jarring shifts in perspective, we’re yanked out of this commercial-grade digital first-person into a coldly panoramic, 16mm third-person. The film flops frequently between these two mediums — perfectly unvarnished, windowboxed video and patiently, meticulously composed celluloid — and the striking discrepancy between them plays a vital role in its belated inciting incident, wherein a stunned Robert silently films a life-or-death emergency, neither intervening nor calling for help. The line between spectatorship and experience blurs. Tragic and traumatic consequences ensue. For a novice, Campos possesses an uncanny mastery of film grammar, and a refreshing commitment to lost cine-virtues like stillness and quiet. There’s no denying the confidence and control of his craft, yet to what end, this fashionably sterile gaze? The man has already been accused, with a critical unanimity that suggests kids copying each other’s homework, of cribbing from the Gus Van Sant and Michael Haneke schools of Chilly, Long-Take Formal Elegance. The comparisons are not without grounding, as the first-time filmmaker’s purposefully off-kilter master shots evoke the same brand of shuddery unease as the ones employed by those love-em-or-hate-em iconoclasts. Yet unlike Elephant, Afterschool doesn’t immerse us in pure milieu, in the spatial and environmental details of its prep school locale — this is a fairly linear narrative, not one of Van Sant’s plotless funereal marches. And excepting the last shot, a voyeuristic, fourth-wall-shattering Gotcha! moment, Campos doesn’t seem particularly interested in blaming all of us for his impeccably filmed nightmare of modern disassociation. This is not, in other words, a Haneke-style guilt-fest.

It might be worse than that, actually. No, Campos’ post-Bella Tarr visual wonders ultimately serve a much less complicated (and far more conventional) function: they’re token signifiers of Robert’s mixed-up headspace. How do we know the kid feels alienated? Cause he shares the screen with lots of empty space, and stares off into smeary, out-of-focus backgrounds. He fares better than some of his co-stars. Campos’ “artfully” askew frames slice off a limb here, a top of a head there. The young ladies are often reduced to mere objects of Robert’s sexual desire/frustration, endless and disembodied legs descending a staircase, tits and ass without a face. This is prodigious aesthetic prowess put to the most dehumanizing of tasks: transforming flesh-and-blood subjects into allegorical pawns, mere cogs in an immaculately constructed Big Message machine. If the framing and staging choices don’t cast the director’s empathy under suspicion, his notions about what teen spirit smells like in the Internet Era certainly do. Lurching about like stoned somnambulists, or like the blank-faced, suicide-victim apparitions of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse, Campos’ young cast of American Apparel models further obscures any insight into modern, media-steeped adolescence. These aren’t human beings so much as mannequin representations, Campos’ mythical “YouTube Generation” incarnate. Van Sant may have romanticized disaffected youth in his stellar Paranoid Park, and even fetishized their impending slaughter in the gorgeous but deeply troublesome Elephant, but at least the dazed and confused youngsters in both those films talked like actual kids. In Afterschool, even the lewd sex banter sounds schematically designed: when one boy taunts another about screwing his sister, his robotic cadence suggests not the callow immaturity of wretched youth, but the repetition of some rigid gospel.

As Tina Fey recently reminded us, high school still runs on bullshit hierarchies, but are said social patterns really this ritualistic, this machine-like? Like all “Suburbia Sucks” bitch-fests, Afterschool swirls its misanthropic shitstorm around the ennui of a fragile and angsty loner. Obsessed with finding and connecting to something “authentic,” of cutting through the perceived artificiality of his insular environment, Robert wields his handheld video camera like a weapon of truth. When his AV-club partner and prospective girlfriend Amy (Addison Timlin) strikes a fashion-model pose during their maiden sexual encounter, he makes like the cameraman in his favorite porno, choking the girl to elicit a genuine, unaffected response. Later, the boy is entrusted with the task of creating a video tribute to a pair of deceased classmates. What he comes up with is miles away from what is expected of him: an amateurishly edited but wholly honest evocation of grief, all “off moments” of pensive reflection, awkward confessions, and less-than-comforting sentiments. No plastic-bag-in-the-wind nonsense here. Just a disquietingly close look at the mourning process. Naturally, it doesn’t go over so hot with the powers that be. Placed in context, Robert’s film-within-a-film provides Afterschool with its single moment of piercing, disarming profundity. Unfortunately, it’s also the movie’s ironic centerpiece, an ode to truth in a work that feels fundamentally false at its very core. Unless we are to here put into effect the Redacted defense — mainly, that all of this is brazenly artificial on purpose, as some sort of meta reflection of our culture’s inherent commitment to poses and postures and performances — the bracing but shallow Afterschool reveals itself as just another Modern Lie, obscuring truth with art-cinema pretension. If this is the alternative, we should take the relative honesty of YouTube videos any day of the week. Those teen farces at least have the benefit of brevity, and the sheer absence of precisely rendered distancing devices. As for the still-promising Campos: a blowhard polemicist hoisted by his own petard? How aptly, exquisitely 2009.

Comments are closed.