Richard Kelly’s new film is based on Richard Matheson’s short fiction “Button, Button,” in which a man gives a struggling couple a wooden box with a single button, promising them that if they press it, they’ll receive a large sum of money, while simultaneously causing the death of someone they do not know. The release of this film adaptation has led to a new paperback edition of Matheson’s story, but in truth, Kelly’s The Box is less an adaptation of “Button, Button” than a ponderous spectacle loosely inspired by it. In fact, the film adapts the 1986 Twilight Zone TV version of “Button, Button” more so than it does Matheson’s original, in that it wisely incorporates that episode’s ending (lest you think that’s giving anything away, this ending is only a beginning in Kelly’s film) rather than the original story’s. Kelly moves away from Matheson’s classically minimal conception of the Prisoner’s Dilemma into a complex scenario of alien manipulation and conspiracy mysteriously linked to the 1976 NASA Viking landing on Mars.

The ambitious, sprawling structure of Kelly’s previous film, Southland Tales, is echoed here, but this time it feels less like the cinematic equivalent of a Pynchon novel, and more like the final season of The X-Files. The implacable uncertainty of the Matheson story is played up by the first part of the film, but as the looming alien plot arc continues to advance, it becomes ever more unwieldy, undermining rather than foregrounding the human drama of Arthur, Norma, and the other inhabitants of Kelly’s fictionalized ’70s-era Virginia. Kelly has spoken in interviews of his desire in this film to re-create “the Glory Days” of his hometown of Langley, VA, and The Box is set in 1976, notably the year after Kelly — whose father worked on NASA’s Mars Viking Lander Program — was born. The historically detailed setting — including gaudy ’70s clothing and interiors — is charming. But the awkward superstructure of the alien plot, replete with its spasms of liquidly luminescent visual effects, only keeps the film from returning to its stronger material, which explores the minimalist drama of “Button, Button” and the palpable tension of Arthur and Norma’s uncertain financial future.

The film employs many of the stylistic elements that are becoming Kelly signatures, including: rapid shots of diegetic text too tantalizingly brief for the viewer to read; thematically centered, and sometimes heavy-handed, literary allusions (Sartre’s play No Exit and, naturally, Matheson’s source material structure this film, much like Graham Green’s “The Destructors” and Richard Adams’ Watership Down did Donnie Darko); and, of course, instantaneous spatio-temporal travel, inevitably linked to colorful visual effects a little too reminiscent of Darko‘s iridescent wormholes. Kelly’s fascination with self-sacrifice and Christian allegory in his debut is likewise central to The Box, but where such an element came off as refreshingly earnest and even revelatory in that earlier film, here the implication seems hackneyed, due in part to Cameron Diaz’s wooden, melodramatic performance as Norma.

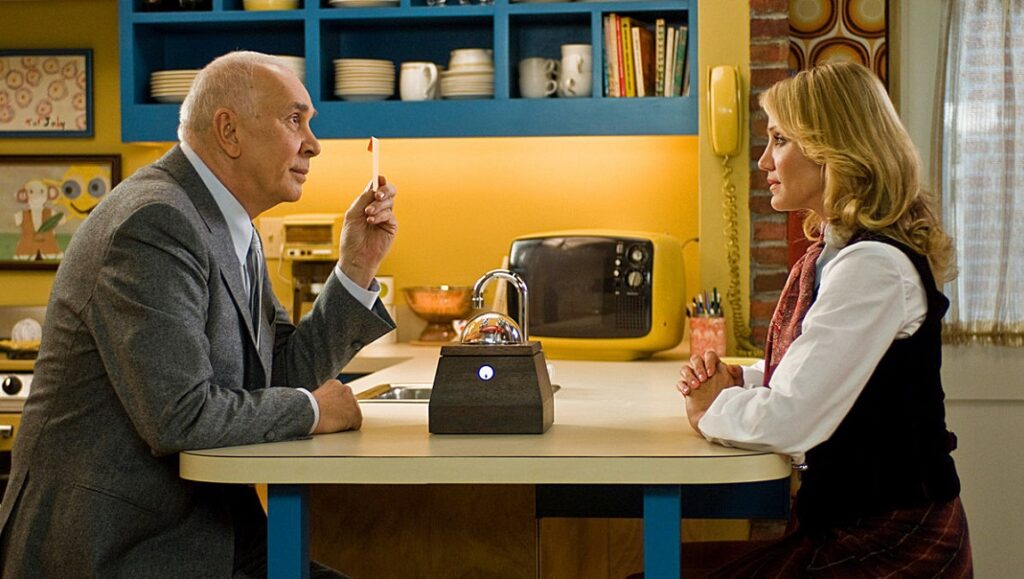

Elsewhere, Kelly’s version of the story’s mysterious Mr. Steward, here spectacularly disfigured (NASA experiment: lightning), is skillfully realized by the magisterial Frank Langella, whose suavely menacing performance is, along with the historical setting, one of the best things about the film. Nevertheless, his character might as well be named Klaatu, so close is Kelly’s conception at points to The Day the Earth Stood Still. Steward’s character in Matheson’s story is chilling precisely because of the lack of exposition concerning his origins and ultimate purpose (in an interview, Langella described his character as “a man who is there to do a job”), but the film’s elaboration on his posthumous involvement in an intergalactic ethical experiment effectively spoils this stark indeterminacy. In Langella’s words, Kelly is to be admired as a director because he “thinks out of the box,” and is a fair assessment where Donnie Darko and Southland Tales are concerned. But with The Box, it seems Kelly has begun to think his way back into a box of his own construction; one which, for all its eccentricity and shiny CGI wormholes, renders his film both predictable and constricted.

Comments are closed.