Part of the appeal of a film like Taste of Cherry—Kiarostami’s minimalist masterpiece, all white-canvas stretches of silence and inaction—lies in its openness to interpretation, in how it invites us to invest meaning in it rather than simply extract the meaning imposed upon it. Minimalism is about encouraging reflection, on form and content both, but Taste of Cherry in particular betrays a deeper understanding of self-reflexivity: its languid pace and elliptical narrative function not only to underscore the passing of time and the finite nature of mortality, a quality common to many minimalist experiments, but also as a kind of meta-commentary on the act of filmmaking itself, a theme Kiarostami has returned to again and again.

Kiarostami’s detractors, of course, dismiss all this conspicuous silence and obscurity as proof of the film’s shallowness. When the film made its way to the U.S. in 1998 (after having won the Palme d’Or at Cannes the year prior), quite a few prominent mainstream critics lambasted Taste of Cherry slamming it as boring and its supporters as pretentious. Roger Ebert rather infamously called Kiarostami “an emperor without any clothes,” whose arthouse sensibilities are “an affectation,” and the sentiment was shared by many others. Ebert believed that Taste of Cherry did not benefit from its own obliqueness, and that the “tired distancing strategies” of its meta-fictional closing sequence—a jarring non-narrative epilogue shot on poor-quality video in which Kiarostami and his crew are shown working on the film—served no real purpose at all. (This final sequence, in fact, strikes me as an inviting and strangely life-affirming celebration of the filmmaking process itself, one that is a crucial aspect of the film’s greatness—but one which is also divisive even among Taste of Cherry‘s supporters, and excised by Kiarostami himself for theatrical presentations in certain national markets; it is mercifully retained on the widely available North American DVD.)

The mystery of Badii’s intentions is not some arbitrary barrier to entry designed to frustrate or distance us from him as an audience, but a meaningful gesture of respect for the complexity of his pain; to know his suffering in detail is to risk an attempt to explain it all away

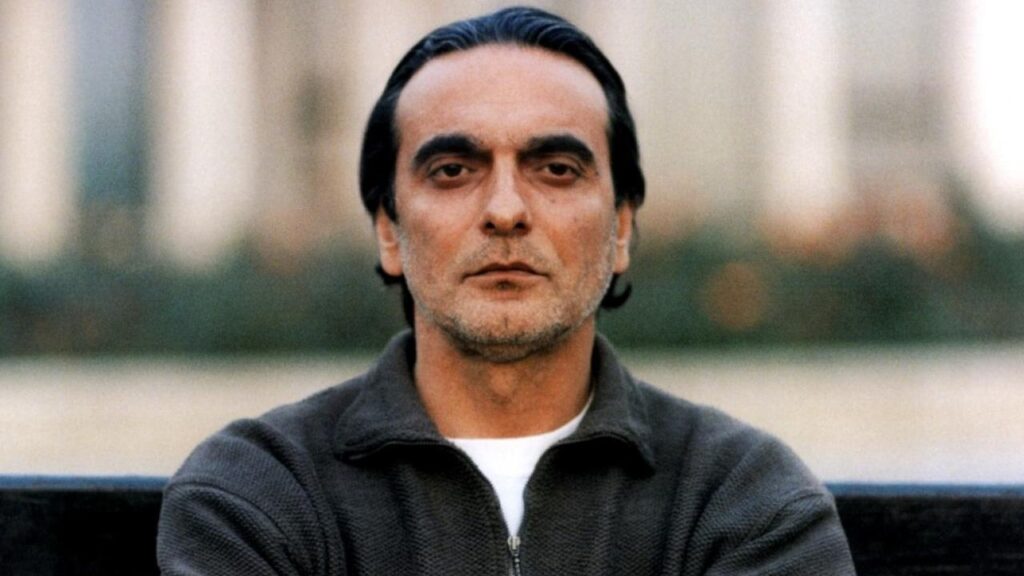

What these objections highlight more than any failings in the film are the very rigid convictions Western audiences hold about how movie narratives should unfold. It’s true that very little conventional action occurs across Taste of Cherry’s 95-minute running time. It’s true that Kiarostami provides us with very little information about Badii, the film’s protagonist, whose journey to find a willing candidate to assist him with his burial after he commits suicide is not fleshed out with the requisite Hollywood backstory. And it’s true, too, that we know next to nothing about this character’s reasons for wanting to end his life, which for some is a completely incomprehensible creative decision: “If we’re to empathize with Badii,” Ebert asks indignantly, “wouldn’t it help to know more about him?” But the idea that we require a character’s thoughts and feelings to be comprehensively explicated in order to empathize with them effectively is based on a whole lot of dubious assumptions, most of which have been instilled in us by a lifetime of rote Hollywood programming. The mystery of Badii’s intentions is not some arbitrary barrier to entry designed to frustrate or distance us from him as an audience, but a meaningful gesture of respect for the complexity of his pain; to know his suffering in detail is to risk an attempt to explain it all away. Specificity trivializes pain, and so by remaining silent Kiarostami speaks universally.

That silence also invites our own participation, which means we have to be willing to do some of the heavy lifting ourselves. In the same way that the war-torn landscapes and wandering characters of Italian neorealism privileged reflection over action, Taste of Cherry drifts and meanders because it values looking more than acting. We’re encouraged to identify less with these characters and this situation than we are with the act of filmmaking itself, and in doing so we become more active participants in Kiarostami’s creation. Which isn’t to say that the film wants simply to “remind” us that we’re watching a movie—we’re not talking about hip po-mo posturing—so much as it wants us to remain conscious of the reality behind what’s unfolding. This is actually a lot closer to what Brecht’s “distancing strategies” were intended to do than the confused ways they’ve been adopted by other contemporary filmmakers: the point was never to coldly isolate an audience from the influence of drama, but to influence an audience with drama in a way that makes them aware of its effects. That’s why the “reality” of the final sequence doesn’t undercut the dramatic impact of the fictional suicide which precedes it—it augments its effect, contrasting the inevitable finality of death with the life-affirming joy of the creative act. Kiarostami wants us to remember that we’re all headed for death, but that our time here is literally what we make of it.

Comments are closed.