Kabali is an Indian gangster film, and the star vehicle for Tamil Nadu star Rajinikanth, the second highest paid Asian actor after Jackie Chan. Rajinikanth is big, but not in the eyes of the Western world; there are several practical reasons for this, chief among them being the sad state of representation/coverage of Indian films in the American/British/English-language press. Tamil-language films fair only slightly better than Bollywood—another method of studio production, and one with a different geographical location. Tamil-language films are produced in the Southeast part of India, attracting English-language viewers. These films’ distributors know their established audience, and they don’t care to venture outside of that comfort zone. In a day’s time, Kabali broke box office records, grossing 48 crore ($7.68 million dollars) across 12,000 screens in India. English-language speakers are not this film’s primary audience.

At the same time, English-language media outlets don’t really care about Indian-language films. Or, to put it more diplomatically: big outlets simply don’t have the budget to cover films that aren’t marketed to a general audience demographic. That would require press releases to alert over-worked editors to the existence of such films, and would allow underpaid freelancers the opportunity to see, let alone write about, Tamil- or even Hindi-language films. These conditions do not exist, and may never exist, because the ideal audience for any English language-speaking publication has not heard of Rajinikanth, and will not hear of Rajinikanth until English language-centric film distributors take a chance on him, and try to sell him as the next big thing.

Kabali is currently playing at Manhattan’s Regal E-Walk 13 cinema, where a ticket to the Friday night screening cost $20.00—the standard amount for a primetime specialty engagement (i.e., any Tamil-language films, many of which are not booked by the relatively Bollywood-centric AMC theater chain). The 7:10pm show was packed anyway—and the first mention of “Super Star Rajinikanth” (his appellative being a contractual obligation) earned rowdy cheers from the audience, likewise the actor’s first onscreen appearance.

But is Kabali actually worth all this?

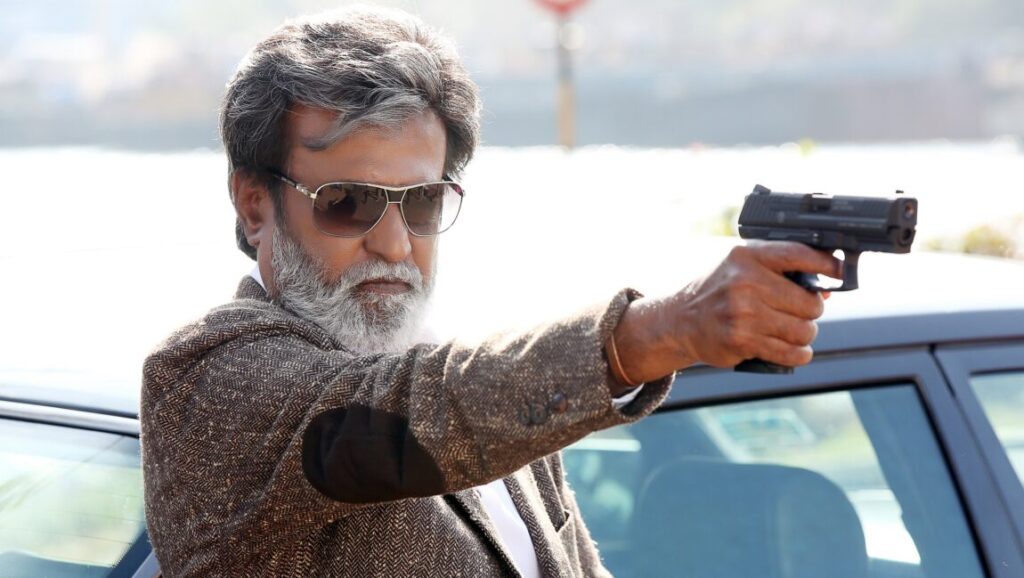

Absolutely, if you know what you’re getting into. Rajinikanth plays the title character, a gangster who bucks expectations; he fights against “gangsterism” by opening the Free Life Foundation, a high school for juvenile delinquents and other undesirables who can’t take the pressure of a normal school education. An ex-con likened to Malcolm X, Nelson Mandela, Che Guevara, Gandhi, and other rebellious political figures promoted in murals peppered throughout the Free Life Foundation, Kabali is a good guy who kills bad guys. It’s just that simple. The main difference between him and drug-dealing gang leader Tony Lee (Winston Chao, in a hilariously wooden performance) is a refusal to cross the same didactic, puritanical line as many Bollywood stars: family is sacred, children are the future, and drugs and alcohol are bad. This is, after all, a Tamil-language super-production, one where every on-screen reference to drugs, drink, and cigarettes is met with an ostentatious disclaimer about the “injurious” nature of these stimulants at the screen’s bottom-left corner.

The plot here is simple: Kabali gets out of jail after years of building up the Free Life Foundation. As soon as he returns, he gets alternatively furious and nostalgic—the two most common expressions of the Indian action film. When his wife and daughter go missing, Kabali takes his sweet time settling scores with Tony Lee and his lieutenants. This feud climaxes in a set piece that’s like the explosive finale of Brian De Palma’s Scarface—the main difference being that Kabali, seated in a plush armchair and surrounded by the bodies he and his loyal men have felled in the name of education, is justified when he guns down Tony Lee. Rajinikanth only kills bad guys, like the pipe-smoking villain he and his chauffeur run over. It would seem that there is no moral gray area here…

…Or is there?

That’s the question that Kabali‘s out-of-the-blue, cliff-hanger ending seems to ask. Or take for example the scene where good guy Jeeva (Dinesh) is assassinated by a group of indistinct thugs. These baddies chuck bottles and use improvised blades and pipes to take Jeeva down, in one of the film’s most tense and agonizingly well-choreographed action scenes. This precedes another scene in which Rajinikanth pointedly uses a broken bottle to stay an attacker’s hand. How do you make sense of that juxtaposition? In the hands of a bad guy, alcohol is a weapon. But a bottle is still glass and rough edges in the hands of a white-hat, tailor-made-suit-wearing hero like Kabali.

Kabali works as well as it does because its creators believe in what is ultimately a hypocritical distinction between good and bad guys. Actors like Rajinikanth are constantly striking poses of grief, remorse, and anger for the sake of establishing their characters’ sincerity. This can feel like artificial chest-puffing, but it’s frequently satisfying too: Rajinikanth’s range may extend from one “smug laugh,” as the film’s English-language closed captioning described it, to the next dour grimace, but the man’s magnetism proves that you don’t need to be a great actor to deliver a great performance. Rajinikanth is consistently charming throughout Kabali‘s doughy but largely entertaining two and a half-hour runtime. And if you accept the character for what he is—a symbol of “hyper-masculine camp,” as founding New York Asian Film Festival programmer Grady Hendrix aptly put it—you may just find yourself with a new favorite summer blockbuster.

Comments are closed.