2017—so far at least—hasn’t been spectacular. In between the deaths of beloved auteurs like Jonathan Demme and Seijun Suzuki, you had 25 beating Lemonade at the Grammy’s, Tom Brady smugly winning another Super Bowl, and Donald Trump being sworn into office (this one might be a little worse than those other two). But as Lil Yachty once told Kyle, “Come on, man, you got so much more to appreciate.” So here at InRO, we’re taking the Boat’s words to heart, and have tried our best to remember some of the worthwhile things from the past few months. So here are the films from the first quarter we’ve deemed noteworthy for the better, or for much-the-much, much worse.

With Personal Shopper, Olivier Assayas returns to the techy, angsty modernity of Irma Vep and Boarding Gate with another hybrid thriller, a sort-of-but-maybe-not ghost story about a possibly clairvoyant young woman, Maureen (Kristen Stewart), trapped between worlds, both literally and figuratively. Her job as the, uh, personal shopper for a famous actress demands that she play act as someone else (whom we rarely see) and separate herself from her own modes of expression (both economic and stylistic). Meanwhile, Maureen’s busy trying to commune with the spirit of her recently deceased brother. This stacking of identities and representations (as well as simultaneously sinister, playful, and deliberately oblique scenes featuring supernatural interference) bring to mind the layering of worlds so prominent in Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s films, collapsing multiple times and spaces into one moment. And the centerpiece here, an extended, hilarious, and excruciatingly suspenseful sequence wherein Maureen texts frantically with what may or may not be a ghost, recalls the quotidian detail of Rivette’s thrillers (specifically Secret Defense). Through it all, Stewart proves herself to be maybe the most volatile modern American actress, someone who vibrates on her own frequency, here a tightly wound ball that radiates outward, firing little electrons of fear and doubt that pick at the bonds of everything around her. This one’s gonna be tough to beat this year. Matt Lynch

With Personal Shopper, Olivier Assayas returns to the techy, angsty modernity of Irma Vep and Boarding Gate with another hybrid thriller, a sort-of-but-maybe-not ghost story about a possibly clairvoyant young woman, Maureen (Kristen Stewart), trapped between worlds, both literally and figuratively. Her job as the, uh, personal shopper for a famous actress demands that she play act as someone else (whom we rarely see) and separate herself from her own modes of expression (both economic and stylistic). Meanwhile, Maureen’s busy trying to commune with the spirit of her recently deceased brother. This stacking of identities and representations (as well as simultaneously sinister, playful, and deliberately oblique scenes featuring supernatural interference) bring to mind the layering of worlds so prominent in Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s films, collapsing multiple times and spaces into one moment. And the centerpiece here, an extended, hilarious, and excruciatingly suspenseful sequence wherein Maureen texts frantically with what may or may not be a ghost, recalls the quotidian detail of Rivette’s thrillers (specifically Secret Defense). Through it all, Stewart proves herself to be maybe the most volatile modern American actress, someone who vibrates on her own frequency, here a tightly wound ball that radiates outward, firing little electrons of fear and doubt that pick at the bonds of everything around her. This one’s gonna be tough to beat this year. Matt Lynch

If there’s one thing that singles out the average modern day superhero film, it’s how indistinct most feel. The cinematic (if you even can call it that) universes of Marvel and DC keep going back to the same insipid well: shot-reverse-shot grammar, drained color palettes highlighted by silver and gray. With the bar set that low, it’s a genuine surprise that Logan not only defies expectations of its genre, but manages a well-crafted character study too. The plot is a familiar one: A hero—Wolverine a.k.a. James “Logan” Howlett ( Hugh Jackman)—must protect a mysterious adolescent (Dafne Keen) from scheming evildoers. But thanks to some great performances—especially Jackman and Patrick Stewart (as the aging Professor X), who dig in to explore the darkest impulses of characters they’ve played going back 17 years now—and director James Mangold’s keen eye for capturing the humanist dimensions in the struggle of his “mutants,” the premise feels fleshed out enough to warrant audience investment beyond just our protagonists being “the good guys.” And though Logan is a gangbusters genre film, the best moments tend more to involve its small scale drama. The highlight of the whole thing may be an extended interlude at a farm house, which details the intricacies of regret and anxiety that have built-up in these characters, and is most exciting before the action even starts. Paul Attard

João Pedro Rodrigues calls The Ornithologist a “western,” which fits in the sense that the director appropriates his culture’s iconography and myth for his own revisionist narrative. Ornithologist is also essentially an adventurer’s film—one filtered through trippy, Pasolini-esque religious imagery. But these juxtapositions may just be blasphemy for blasphemy’s sake: Having a gay St. Anthony fuck a deaf and mute Jesus, get almost castrated by Chinese missionaries, and be hunted by topless centaurian women is sure to make conservatives in Portugal blush or gasp, but it never signifies a particularly coherent transformation (unlike, say, the metaphorically loaded trials endured by the transgender woman in To Die Like a Man). Rodrigues seems almost on to something when he starts inserting himself in his lead actor’s place throughout the second half of Ornithologist—suggesting that the erratic confrontations in his film are a way of working through some very personal anxieties (and certain episodic segments here do faintly call back to his earlier shorts, China China and Mahjong)—but the full meaning of that strategy never really comes across. It doesn’t help that this is Rodrigues’s most diffuse film narratively, prone to long, wandering breaks between the action. Thankfully, Ornithologist is a lot more formally playful than Rodrigues’s previous film, The Last Time I Saw Macau. But if the director is going to keep making films in this register, moving farther afield from the pop-art gravitas of his brilliant Two Drifters, he’ll need to tap into the core emotional vulnerabilities that made his early films feel so passionate. Sam C. Mac

João Pedro Rodrigues calls The Ornithologist a “western,” which fits in the sense that the director appropriates his culture’s iconography and myth for his own revisionist narrative. Ornithologist is also essentially an adventurer’s film—one filtered through trippy, Pasolini-esque religious imagery. But these juxtapositions may just be blasphemy for blasphemy’s sake: Having a gay St. Anthony fuck a deaf and mute Jesus, get almost castrated by Chinese missionaries, and be hunted by topless centaurian women is sure to make conservatives in Portugal blush or gasp, but it never signifies a particularly coherent transformation (unlike, say, the metaphorically loaded trials endured by the transgender woman in To Die Like a Man). Rodrigues seems almost on to something when he starts inserting himself in his lead actor’s place throughout the second half of Ornithologist—suggesting that the erratic confrontations in his film are a way of working through some very personal anxieties (and certain episodic segments here do faintly call back to his earlier shorts, China China and Mahjong)—but the full meaning of that strategy never really comes across. It doesn’t help that this is Rodrigues’s most diffuse film narratively, prone to long, wandering breaks between the action. Thankfully, Ornithologist is a lot more formally playful than Rodrigues’s previous film, The Last Time I Saw Macau. But if the director is going to keep making films in this register, moving farther afield from the pop-art gravitas of his brilliant Two Drifters, he’ll need to tap into the core emotional vulnerabilities that made his early films feel so passionate. Sam C. Mac

As the son of Anthony Perkins, who famously portrayed Norman Bates in the seminal Alfred Hitchcock thriller Psycho, director Oz Perkins was sure to catch the horror bug. The Blackcoat’s Daughter, which toured the 2015 festival circuit under the less catchy but more lyrical title of February, is his first film, though it was released after what was meant to be his follow-up, the Netflix original I Am the Pretty Thing that Lives in the House. Even if it had been released first, however, the film in no way feels like a debut. Perkins arrives as a confident and intelligent stylist in an age when horror cinema — the most cyclical of American film genres — is back in “reinvention mode.” The film shies away from the nihilistic banalities of torture porn and bad Blumhouse movies, focusing instead on humanistic horror and emotional turmoil. Perkins said the narrative, which tracks a pair of parallel storylines—featuring an escaped mental patient (Emma Roberts) and a pair of snow-bound students (Kiernan Shipka and Lucy Boyton) stranded at their all-girl boarding school, respectively—was partially informed by the sudden death of his parents. In a film that touches on the demonic and the supernatural, it’s grief that emerges as the most malevolent presence, an invisible wound more painful and lasting than even the most vicious slash of the knife. Drew Hunt

As the son of Anthony Perkins, who famously portrayed Norman Bates in the seminal Alfred Hitchcock thriller Psycho, director Oz Perkins was sure to catch the horror bug. The Blackcoat’s Daughter, which toured the 2015 festival circuit under the less catchy but more lyrical title of February, is his first film, though it was released after what was meant to be his follow-up, the Netflix original I Am the Pretty Thing that Lives in the House. Even if it had been released first, however, the film in no way feels like a debut. Perkins arrives as a confident and intelligent stylist in an age when horror cinema — the most cyclical of American film genres — is back in “reinvention mode.” The film shies away from the nihilistic banalities of torture porn and bad Blumhouse movies, focusing instead on humanistic horror and emotional turmoil. Perkins said the narrative, which tracks a pair of parallel storylines—featuring an escaped mental patient (Emma Roberts) and a pair of snow-bound students (Kiernan Shipka and Lucy Boyton) stranded at their all-girl boarding school, respectively—was partially informed by the sudden death of his parents. In a film that touches on the demonic and the supernatural, it’s grief that emerges as the most malevolent presence, an invisible wound more painful and lasting than even the most vicious slash of the knife. Drew Hunt

Who’s John Wick? He’s the world’s greatest assassin, played with stoic intensity by Keanu Reeves. Ok, that’s the basic stuff, but who is he really—like, as an actual character, beyond his job description. Director Chad Stahelski doesn’t seem to know the answer or frankly doesn’t care; he sees Wick as a vessel for explosive set-pieces, goosing audience amusement, which is why John Wick: Chapter 2 feels so empty. Wick has a bounty on his head from bad guy Santino D’Antonio (Riccardo Scamarcio), which gives him his latest excuse to basically just kill a bunch of people in “cool” ways. There are some memorable moments involving his kills, including three people done-in by pencils, and… well, that’s basically it. The film rarely feels jolted by any real sense of excitement, or imagination, opting instead for a relentless parade of fatalities. Lacking the grace someone like Johnny To would bring to an action set-piece, things here more often than not are built around blunt force. Seldom does a moment go by that doesn’t feel exhausting, and with a runtime of two hours, the extent of that exhaustion is felt. For many victims that cross Wick’s path, the end is the only mercy, and the same goes for us. PA

Who’s John Wick? He’s the world’s greatest assassin, played with stoic intensity by Keanu Reeves. Ok, that’s the basic stuff, but who is he really—like, as an actual character, beyond his job description. Director Chad Stahelski doesn’t seem to know the answer or frankly doesn’t care; he sees Wick as a vessel for explosive set-pieces, goosing audience amusement, which is why John Wick: Chapter 2 feels so empty. Wick has a bounty on his head from bad guy Santino D’Antonio (Riccardo Scamarcio), which gives him his latest excuse to basically just kill a bunch of people in “cool” ways. There are some memorable moments involving his kills, including three people done-in by pencils, and… well, that’s basically it. The film rarely feels jolted by any real sense of excitement, or imagination, opting instead for a relentless parade of fatalities. Lacking the grace someone like Johnny To would bring to an action set-piece, things here more often than not are built around blunt force. Seldom does a moment go by that doesn’t feel exhausting, and with a runtime of two hours, the extent of that exhaustion is felt. For many victims that cross Wick’s path, the end is the only mercy, and the same goes for us. PA

Words like “raw” and “fearless” come up awfully short as descriptors for Joanna Arnow’s autobiographical nonfiction work i hate myself : ), a document of the filmmaker’s relationship with a crass, heavy-drinking amateur stand-up comedian/anarchist that acts as a means of answering her own question: “Is it a good idea to be dating James?” The self-interrogating extends to the construction of the film itself, as Arnow includes conversations with her editor (who appears each time fully nude, a witty quid-pro-quo to her own physical/psychological/

Words like “raw” and “fearless” come up awfully short as descriptors for Joanna Arnow’s autobiographical nonfiction work i hate myself : ), a document of the filmmaker’s relationship with a crass, heavy-drinking amateur stand-up comedian/anarchist that acts as a means of answering her own question: “Is it a good idea to be dating James?” The self-interrogating extends to the construction of the film itself, as Arnow includes conversations with her editor (who appears each time fully nude, a witty quid-pro-quo to her own physical/psychological/

Although it was a late addition to last year’s (especially strong) Cannes Competition slate, Asghar Farhadi’s The Salesman eventually took home both the festival’s actor and screenplay prizes (not to mention the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar earlier this year). Given Farhadi’s reputation as a world-class dramatist, the screenplay win wasn’t exactly unexpected. Less predictable was precisely how Farhadi would incorporate Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman—from which the film’s title is taken—into his trademark moral quagmires, which are largely set in contemporary Iran. (His last film, The Past, was set in Paris.) The answer, it turns out, would be by centering the story around married couple Emad and Rana (Shahab Hosseini and Taraneh Alidoosti), who star in a local production of Miller’s classic play. That’s fitting given that the film so fluidly negotiates between its opposing poles: claustrophobic interiors and stark exteriors (physical and emotional); the public and private spheres of Iranian life; the appearance or reputation of something and its base reality. From the opening scene alone, in which we see the couple evacuate a crumbling building, Farhadi forces one assumption only to turn it on its head moments later. (A presumed earthquake turns out to be the side effect of a nearby construction site.) An inciting act of violence—Rana’s assault by a stranger in the couple’s new apartment—creates fissures that spread as the film goes along, building in pressure until the extended climax: a harrowing negotiation between personal injury and public shame. It’s riveting, if a touch schematic by Farhadi’s high standards, but lent a distinct force by his increasingly fluid (and under-appreciated) mise-en-scène. (Even a throwaway shot of a mirror being carried up an apartment building staircase is casually striking.) The film’s conclusion may ultimately be pyrrhic, but The Salesman itself is a triumph. Lawrence Garcia

Although it was a late addition to last year’s (especially strong) Cannes Competition slate, Asghar Farhadi’s The Salesman eventually took home both the festival’s actor and screenplay prizes (not to mention the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar earlier this year). Given Farhadi’s reputation as a world-class dramatist, the screenplay win wasn’t exactly unexpected. Less predictable was precisely how Farhadi would incorporate Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman—from which the film’s title is taken—into his trademark moral quagmires, which are largely set in contemporary Iran. (His last film, The Past, was set in Paris.) The answer, it turns out, would be by centering the story around married couple Emad and Rana (Shahab Hosseini and Taraneh Alidoosti), who star in a local production of Miller’s classic play. That’s fitting given that the film so fluidly negotiates between its opposing poles: claustrophobic interiors and stark exteriors (physical and emotional); the public and private spheres of Iranian life; the appearance or reputation of something and its base reality. From the opening scene alone, in which we see the couple evacuate a crumbling building, Farhadi forces one assumption only to turn it on its head moments later. (A presumed earthquake turns out to be the side effect of a nearby construction site.) An inciting act of violence—Rana’s assault by a stranger in the couple’s new apartment—creates fissures that spread as the film goes along, building in pressure until the extended climax: a harrowing negotiation between personal injury and public shame. It’s riveting, if a touch schematic by Farhadi’s high standards, but lent a distinct force by his increasingly fluid (and under-appreciated) mise-en-scène. (Even a throwaway shot of a mirror being carried up an apartment building staircase is casually striking.) The film’s conclusion may ultimately be pyrrhic, but The Salesman itself is a triumph. Lawrence Garcia

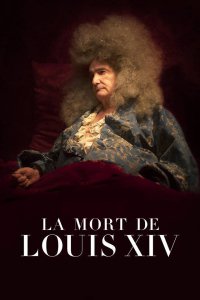

The works comprising Catalan provocateur Albert Serra’s oeuvre have demonstrated his penchant for humanizing (sometimes forcibly) historical figures of some renown. With The Death of Louis XIV, Serra sticks to this m.o. but calibrates his approach so as to craft something altogether more mature and compelling. Where Story of My Death reveled in the grotesquerie of humankind as a means to subvert mythic notions of Casanova, here Serra avoids the temptation of lingering on the titular king’s (Jean-Pierre Léaud) increasingly gangrenous leg and instead focuses on the absurdity of courtly traditions and the fragility of the fading monarch at the center of this spectacle. Brilliantly, all of Serra’s film, save its opening scene, occupies a single set—the king in his royal bed—and the visual aesthetic remains constant even as its emotional and narrative heft lessen with each passing scene. This delicate touch from Serra is a welcome surprise and a remarkable feat of craft—nothing before our eyes changes much, but by the end things feel far grimmer, our judgments far softer, and the man in the frame far more human. Luke Gorham

The works comprising Catalan provocateur Albert Serra’s oeuvre have demonstrated his penchant for humanizing (sometimes forcibly) historical figures of some renown. With The Death of Louis XIV, Serra sticks to this m.o. but calibrates his approach so as to craft something altogether more mature and compelling. Where Story of My Death reveled in the grotesquerie of humankind as a means to subvert mythic notions of Casanova, here Serra avoids the temptation of lingering on the titular king’s (Jean-Pierre Léaud) increasingly gangrenous leg and instead focuses on the absurdity of courtly traditions and the fragility of the fading monarch at the center of this spectacle. Brilliantly, all of Serra’s film, save its opening scene, occupies a single set—the king in his royal bed—and the visual aesthetic remains constant even as its emotional and narrative heft lessen with each passing scene. This delicate touch from Serra is a welcome surprise and a remarkable feat of craft—nothing before our eyes changes much, but by the end things feel far grimmer, our judgments far softer, and the man in the frame far more human. Luke Gorham

Mehrdad Oskouei’s great documentary Starless Dreams relies largely on that most common of doc techniques: the interview. Inside one of Tehran’s juvenile corrections facilities, a group of teenage girls tell their stories to the camera with a remarkable candor and heartbreaking self-awareness of the various injustices they’ve suffered. Oskouei understands that the most vital role he could play in their narratives is a minimal one, and so his voice is heard only off-camera, gently prompting broader considerations on the nature of happiness, forgiveness, and faith. Likewise, his filmmaking offers subtle expansions on the thoughts and ideas expressed by his subjects. When one girl describes the corrections facility as a place where “pain drips from the walls,” Oskouei punctuates the lament with an image of thawing snow on a windowpane. This image not only suggests the sadness of the girl’s reality, but also evokes the hope for change that Oskouei invests in her—one which pays off in the improving circumstances of at least some of the inmates by the end of Starless Dreams. These gestures from the director deepen his 75-minute feature’s sense of artistry, but its emotional capacity is reached through more humanist ambitions. Much like Edet Belzberg’s magnificent Children Underground, the true act of transcendence here is in giving a platform to otherwise voiceless souls of such a boundless strength and character. SCM

Mehrdad Oskouei’s great documentary Starless Dreams relies largely on that most common of doc techniques: the interview. Inside one of Tehran’s juvenile corrections facilities, a group of teenage girls tell their stories to the camera with a remarkable candor and heartbreaking self-awareness of the various injustices they’ve suffered. Oskouei understands that the most vital role he could play in their narratives is a minimal one, and so his voice is heard only off-camera, gently prompting broader considerations on the nature of happiness, forgiveness, and faith. Likewise, his filmmaking offers subtle expansions on the thoughts and ideas expressed by his subjects. When one girl describes the corrections facility as a place where “pain drips from the walls,” Oskouei punctuates the lament with an image of thawing snow on a windowpane. This image not only suggests the sadness of the girl’s reality, but also evokes the hope for change that Oskouei invests in her—one which pays off in the improving circumstances of at least some of the inmates by the end of Starless Dreams. These gestures from the director deepen his 75-minute feature’s sense of artistry, but its emotional capacity is reached through more humanist ambitions. Much like Edet Belzberg’s magnificent Children Underground, the true act of transcendence here is in giving a platform to otherwise voiceless souls of such a boundless strength and character. SCM

It’s hard to imagine a director having more fun on set than Paul W.S. Anderson, from his swashbuckling adaptation of The Three Musketeers—which featured two giant steampunk-esque airships fighting each other—to his Resident Evil franchise, an apocalyptic tale that’s breadth somehow spans a genetic research facility and the Nevada desert. In 2012, Anderson gave us Resident Evil: Retribution, a gonzo action masterpiece that threw every character, concept, and set-piece the series had amassed at the screen, and found a way to blend it all into a work that penetrated the very idea of escapism. Unfortunately, he may have used up all of his great ideas on that one, because Resident Evil: The Final Chapter feels considerably less inspired. The editing fires off more rapidly and sloppily than in the series’ other films, emphasizing a weird montage-like effect that’s uncharacteristically amateurish. And the plot sticks Alice (Milla Jovovich) with poorly-acted randos for most of the run-time. Even the basic set-up this time (Alice has to infiltrate the setting of the first film) makes this feel more like a tacked-on epilogue than a proper “Final Chapter.” But Anderson does let loose his crazy sometimes—including one set-piece involving an army of flaming zombies—and there’s just enough closure offered here for Alice’s character to make things worthwhile. “We’ve played a long game, you and I, but now it’s over,” Dr. Alexander Isaacs (Iain Glen) tells Alice, and the line’s as much directed to her as it is to Anderson’s audience: This director has toyed with expectations for some time now, turning a braindead video game franchise into some of the smartest action films around. The Final Chapter disappoints because Anderson has no surprises left. PA

What a difference a few wispy voiceovers make: 2011’s The Tree of Life, which marked the formerly reclusive filmmaker Terence Malick‘s return to theaters, was heralded by many as a major triumph and an impressive comeback, but today, after four films in the same approximate vein, Malick has become a punchline. Who saw that coming? Song to Song, his latest in what has been an uncharacteristic burst of creativity, has much in common with The Tree of Life, including its profound recognition of the sublime in everyday moments (represented, once again, by Emmanuel Lubezki’s beatific, gliding camerawork) and soul-searching characters. Perhaps it’s this sense of familiarity, or the fact that Malick’s settings are becoming a bit more superficial — Song to Song follows a bunch of pretty people (Rooney Mara, Ryan Gosling, Michale Fassbender) involved in the trendy Austin music scene; his last film, Knight of Cups, took place in Hollywood — in comparison to his ethereal, spiritualistic approach. And yet, it’s the approach that’s most important. Malick’s movies challenge stylistic assumptions and create unique expressions out of elemental forces: light, sound, movement. These might be boring or unfashionable concepts in 2017, but Malick’s art, which uses human experience to consider the very notion of art itself, has never felt more vital. DH

What a difference a few wispy voiceovers make: 2011’s The Tree of Life, which marked the formerly reclusive filmmaker Terence Malick‘s return to theaters, was heralded by many as a major triumph and an impressive comeback, but today, after four films in the same approximate vein, Malick has become a punchline. Who saw that coming? Song to Song, his latest in what has been an uncharacteristic burst of creativity, has much in common with The Tree of Life, including its profound recognition of the sublime in everyday moments (represented, once again, by Emmanuel Lubezki’s beatific, gliding camerawork) and soul-searching characters. Perhaps it’s this sense of familiarity, or the fact that Malick’s settings are becoming a bit more superficial — Song to Song follows a bunch of pretty people (Rooney Mara, Ryan Gosling, Michale Fassbender) involved in the trendy Austin music scene; his last film, Knight of Cups, took place in Hollywood — in comparison to his ethereal, spiritualistic approach. And yet, it’s the approach that’s most important. Malick’s movies challenge stylistic assumptions and create unique expressions out of elemental forces: light, sound, movement. These might be boring or unfashionable concepts in 2017, but Malick’s art, which uses human experience to consider the very notion of art itself, has never felt more vital. DH

If socially conscious criticism is now the norm, then from a distance, it’s difficult to not be skeptical of the critical and commercial success of Get Out, Jordan Peele’s horror-comedy about Chris, a young black man (Daniel Kaluuya) who goes on a weekend trip to the family estate of his white girlfriend (Allison Williams). To be sure, Peele capitalizes on the current social climate—what satire doesn’t?—but that shouldn’t take away from what will stand as one of the sharpest and most assured directorial debuts of the year. Remarkably intelligent and wickedly hilarious, Get Out elegantly weaves together sociopolitical commentary and horror, particularly in its airtight first half, which ably milks the premise for all it’s worth. Look no further than the improbably effective hypnotism scene for Kaluuya’s impressive lead performance and Peele’s sharp directorial instincts. Other pleasures abound, too: Betty Gabriel as a sinister, hilariously disturbed housekeeper; a horror-movie chamber that’s basically a fraternity-house room; the overall off-kilter mode and unnerving vibe. (Less appealing is the comic relief provided by Lil Rel Howley, which, apart from some obviousness, squanders some potentially incisive moments.) The horror-movie finale may strike some as muddled in its real-world resonance—and there are details one could nitpick—but it’s so viscerally effective that its abstract ideas gain potency. Is it any surprise, then, that the flash of a camera is used as a wake-up call? Lawrence G

If socially conscious criticism is now the norm, then from a distance, it’s difficult to not be skeptical of the critical and commercial success of Get Out, Jordan Peele’s horror-comedy about Chris, a young black man (Daniel Kaluuya) who goes on a weekend trip to the family estate of his white girlfriend (Allison Williams). To be sure, Peele capitalizes on the current social climate—what satire doesn’t?—but that shouldn’t take away from what will stand as one of the sharpest and most assured directorial debuts of the year. Remarkably intelligent and wickedly hilarious, Get Out elegantly weaves together sociopolitical commentary and horror, particularly in its airtight first half, which ably milks the premise for all it’s worth. Look no further than the improbably effective hypnotism scene for Kaluuya’s impressive lead performance and Peele’s sharp directorial instincts. Other pleasures abound, too: Betty Gabriel as a sinister, hilariously disturbed housekeeper; a horror-movie chamber that’s basically a fraternity-house room; the overall off-kilter mode and unnerving vibe. (Less appealing is the comic relief provided by Lil Rel Howley, which, apart from some obviousness, squanders some potentially incisive moments.) The horror-movie finale may strike some as muddled in its real-world resonance—and there are details one could nitpick—but it’s so viscerally effective that its abstract ideas gain potency. Is it any surprise, then, that the flash of a camera is used as a wake-up call? Lawrence G

Mamoru Oshii’s original film adaptation of Masamune Shirow’s Ghost in the Shell manga is absolutely a watershed of Japanese anime, but that’s kind of like saying the 1982 Tron is a watershed of Western science-fiction. Oshii’s film had a tremendous influence on the style and content of anime as a medium going forward, but its greatest achievement has to be the conception and realization of its technologically advanced world, and the visionary futurism it represents. The director’s years-later sequel, Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence, built from a foundation of abstract character sketches and vague philosophies a truly complex meditation on Eastern spiritualism as it relates to the moral and aesthetic implications of man’s relationship with, and reliance on, machines. American filmmaker Rupert Sanders’s Ghost in the Shell falls short of Oshii’s more cerebral ambitions in Innocence, and it never quite realizes its dystopian cityscape in as immersive and captivating a way as the original GitS, but it’s nonetheless a satisfying gloss, one with maybe the most coherent and engaging narrative of any effort in this franchise, and a real reverence for said franchise’s core ideas and principles. The film’s critics cite the “problematic” racial politics of its casting, but it’s hard to fault Sanders for putting a white actress in the role of a cyborg who’s never had a clear racial identity to begin with—and even more so when considering the history of anime’s relationship with Western animation, and its own cultural white-washing. Ghost in the Shell has always been about erasing borders between the synthetic and organic, about the fluidity of identity. Sanders’s thoughtful, briskly paced pop entertainment ingratiates itself into that vision. SCM

Mamoru Oshii’s original film adaptation of Masamune Shirow’s Ghost in the Shell manga is absolutely a watershed of Japanese anime, but that’s kind of like saying the 1982 Tron is a watershed of Western science-fiction. Oshii’s film had a tremendous influence on the style and content of anime as a medium going forward, but its greatest achievement has to be the conception and realization of its technologically advanced world, and the visionary futurism it represents. The director’s years-later sequel, Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence, built from a foundation of abstract character sketches and vague philosophies a truly complex meditation on Eastern spiritualism as it relates to the moral and aesthetic implications of man’s relationship with, and reliance on, machines. American filmmaker Rupert Sanders’s Ghost in the Shell falls short of Oshii’s more cerebral ambitions in Innocence, and it never quite realizes its dystopian cityscape in as immersive and captivating a way as the original GitS, but it’s nonetheless a satisfying gloss, one with maybe the most coherent and engaging narrative of any effort in this franchise, and a real reverence for said franchise’s core ideas and principles. The film’s critics cite the “problematic” racial politics of its casting, but it’s hard to fault Sanders for putting a white actress in the role of a cyborg who’s never had a clear racial identity to begin with—and even more so when considering the history of anime’s relationship with Western animation, and its own cultural white-washing. Ghost in the Shell has always been about erasing borders between the synthetic and organic, about the fluidity of identity. Sanders’s thoughtful, briskly paced pop entertainment ingratiates itself into that vision. SCM

“In utero fetus goads expectant mother into a killing spree using little more than muddled logic and horrifying giggles” would be a fair one-line synopsis for Alice Lowe’s (Sightseers) directorial debut, Prevenge, an outré description that proves both apt and misleading for a film that possesses such surprising subtlety. Prevenge establishes its precise rhythms early: Ruth (Lowe) encounters a couple loathsome misogynists (with the DJ Dan sequence proving to be the film’s high point) and dispenses a bit of kick-ass gestational justice, or so the audience is encouraged to feel. After reflecting on the necessity of her slayings, Ruth meets with her midwife (Joe Hartley), a by-all-accounts decent and caring woman who Ruth treats with contempt and showers with misanthropic confessionals. This pattern—murder, muse, midwife—continues throughout Prevenge’s runtime, but with some significant alterations: one victim escapes, others show themselves to be less deserving or even completely undeserving of the demise they meet, and Ruth’s motivational underpinnings begin to come into focus. Horror fans checking in for the gore won’t find it lacking, but despite the sheer amount of blood spilled on screen, Lowe smartly frames the carnage through a relatively minimalist lens, never lingering too long or showing too much (outside an early gross-out gag) in anticipation of the more thought-provoking moments to come. Yet while these late-film developments prove surprisingly affecting for a genre effort like this, Prevenge is still, by its own design, a bit formulaic. Luke G

“In utero fetus goads expectant mother into a killing spree using little more than muddled logic and horrifying giggles” would be a fair one-line synopsis for Alice Lowe’s (Sightseers) directorial debut, Prevenge, an outré description that proves both apt and misleading for a film that possesses such surprising subtlety. Prevenge establishes its precise rhythms early: Ruth (Lowe) encounters a couple loathsome misogynists (with the DJ Dan sequence proving to be the film’s high point) and dispenses a bit of kick-ass gestational justice, or so the audience is encouraged to feel. After reflecting on the necessity of her slayings, Ruth meets with her midwife (Joe Hartley), a by-all-accounts decent and caring woman who Ruth treats with contempt and showers with misanthropic confessionals. This pattern—murder, muse, midwife—continues throughout Prevenge’s runtime, but with some significant alterations: one victim escapes, others show themselves to be less deserving or even completely undeserving of the demise they meet, and Ruth’s motivational underpinnings begin to come into focus. Horror fans checking in for the gore won’t find it lacking, but despite the sheer amount of blood spilled on screen, Lowe smartly frames the carnage through a relatively minimalist lens, never lingering too long or showing too much (outside an early gross-out gag) in anticipation of the more thought-provoking moments to come. Yet while these late-film developments prove surprisingly affecting for a genre effort like this, Prevenge is still, by its own design, a bit formulaic. Luke G

Every once and awhile, an art-film pops up branding itself as exceptionally “disgusting” or “nauseating”—some of these include Ichi the Killer, Antichrist, Martyrs, and now Julia Ducournau’s Raw clearly wishes to be added to the list. French veterinary school student Justine (newcomer Garance Marillier) must overcome anxiety, constant bullying, and… a growing need to eat human flesh. With its blatantly obvious metaphor for a “voracious” desire to fit in, Ducournau reveals her film’s nastiness at every turn; one prolonged sequence features Justine accidentally cutting off her older sister’s finger and then eating it in front of her. Unfortunately, the film doesn’t develop Justine beyond her cannibalism. She’s so stoic in her every confrontation with older peers that it’s hard to invest in her character beyond caring to see who she eats next. That the ending of Raw is stolen straight out of Goosebumps doesn’t help its cause either. PA

Comments are closed.