In an effort to reboot our music coverage, In Review Online is launching monthly features devoted to reviewing new album releases. Last month, we launced εὐδαιμονία (or, Eudaimonia), which we’re presenting in collaboration with the upcoming quarterly journal of the same name, and which will spotlight five worthwhile contemporary music releases, plus one older one, with no genre boundaries. Issue #2 features the latest album from critically acclaimed indie-rocker Mitski; the fourth album by alt-R&B singer-songwriter/producer Blood Orange (A.K.A. Devonté Hynes); two EPs by the electronic artist Iglooghost (A.K.A. Seamus Malliagh); a new work from modern classical luminary Anna Meredith; the second album by Kansas City band Shy Boys; and a retrospective review of Bruce Springsteen’s 1982 album Nebraska.

Meanwhile, there’s Anno: Four Seasons by Anna Meredith & Antonio Vivaldi, a callback to her day job as a proper classical composer. Working with the Scottish Ensemble, the project is to musically annotate that deathless workhorse, Vivaldi’s “Four Seasons,” slotting Meredith’s pieces around straightforward renditions. There are moments here where Meredith rises and builds in familiarly excitable fashion: snip “Bloom” (Autumn) and “Low Light” (Winter), which take those familiar start-stop mash-ups and run with them for a gratifying length. Ditto “Stoop” (Spring), which ends with a very insistently rapped-out drumbeat familiar from Meredith’s shows, where she gleefully whacks the shit out of a snare, while strings breathlessly play the same rising chromatic lines over and over.

As a presumably commissioned exercise, Anno is perfectly good music to work to. There’s not much that can be done to freshen renditions of Vivaldi’s signature, though the playing is vigorous and lively as can be. Meredith’s work seems sometimes less disruptive than the equivalent of a graphic designer pulling a color from a still and using it for a page background; the effect, if listened to straight through, tends to dilute her bold voice. Cull her boldest cuts and wait for more. I have repeatedly referred to her as “the light and the truth” without feeling I’m exaggerating much, and this does nothing to diminish my anticipation of what’s to come. Vadim Rizov

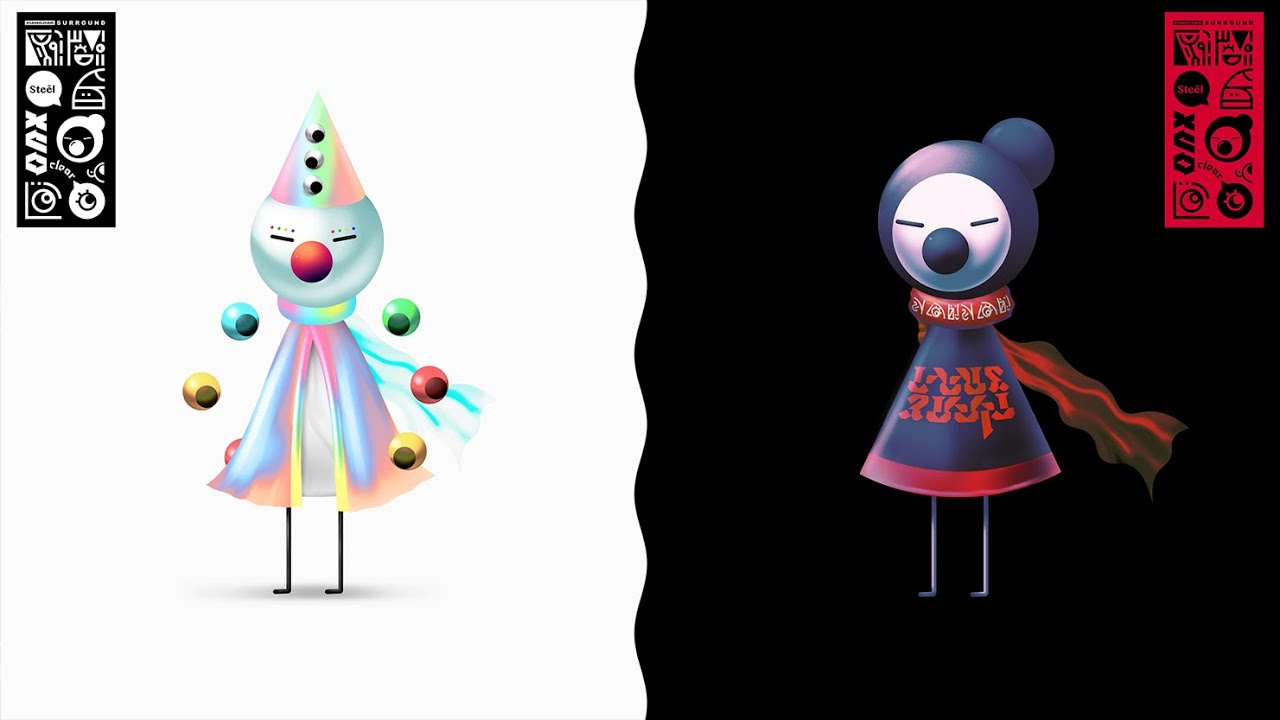

Coming off the momentum of Neō Wax Bloom, Malliagh continues to assert himself as a fascinating creative voice with two 2018 EPs, Clear Tamei and Steel Mogu. These releases see Malliagh broadening the scope of the fantastical mythos that gave definition to Neō Wax Bloom, the details of which are more interesting as extra-textual color than narrative, but nonetheless afford Malliagh a foundation to which he can anchor his idiosyncratic ideas. Clear Tamei takes its inspiration from ‘a being of light,’ and as such Malliagh allows more melodies to emerge from the ruckus. This collision of the melodic and amelodic is combined with Malliagh’s airy vocals, sung in an imagined language, and as such Clear Tamei achieves the ‘alien artifact’ vibe that Malliagh is clearly striving for.

Steel Mogu employs similar formal strategies, but acts as aesthetic counterpoint — with a harder, grimier sound. The looseness and elegance of Clear Tamei’s melodies are replaced by cranked-up drum machines with heavy syncopation. The songs still have a definite shape and design amid the seeming chaos, but these are motivated by adrenaline and drive. The way both EPs speak to one another is perhaps a bit obvious, but the variation makes a strong case for the versatility of the Iglooghost project. Malliagh is clearly an artist with a wealth of ideas — some avant garde, some contemporary, some retro, some quite silly. But the interplay between them is special. M.G. Mailloux

That isn’t to say all of Mitski’s sonic ideas are successful: the stretch from “Me and My Husband” to “A Horse Named Cold Air” comes off too sketch-like, spanning half-formed dream pop (“Come Into the Water”), mopey disco (“Nobody”), and even what sounds like a Radiohead rip (the piano melody of ‘Horse’ is strikingly similar to that of “Pyramid Song”). But after all these misfires, Be the Cowboy finds its way again with the deliberately distended ballad “Two Slow Dancers.” At four minutes, it’s the longest song on the album, and Mitski’s fragile voice floats over its plodding synths, capturing a fleeting moment: reuniting with an old flame you’ve forgotten, being once again in each others arms and trying to make that all-to-brief encounter last for an eternity. Then reality hits, with a refrain of “to think that we could stay the same” jettisoning any quixotic ideals of everlasting love — and the brutal honesty reaching its peak when a dramatic string section helps articulate a distinct melancholy. It’s the most compellingly mature song of Mitski’s career thus far, riding a bitter wave of remorse off into the sunset and finally “being the cowboy” in her own carefully constructed narrative. Paul Attard

“Feelings never had no ethics / Feelings never have been ethical” goes the refrain of “Nappy Wonder,” and it’s a perfect example of the Kierkegaardian lens Hynes uses in his narratives of black life, privilege, and self-expression. Negro Swan also manifests this through the presence of one of its featured performers — transgender rights activist Janet Mock, who narrates the album and reinforces and reframes its songs through her own perspective on issues such as familial support, self-esteem, and the pursuit of destiny. These searching thematic and narrative ambitions are paired with a gauzy jazz aesthetic, with lots of flutes and reverb-ed saxophone, and which occasionally breaks into gospel and even hip-hop forms. Hynes’s lyrics can also tend a toward the ambiguous and indistinct, leaving Mock to often vocalize the music’s ethical concerns (i.e, its most Kierkegaardian aspects), while Hynes’s own songwriting rarely deepens the engagement with these subjects. However, expectations of the impressionistic R&B style that is Blood Orange’s hallmark do help alleviate some of the tension of that which is unsaid, allowing Negro Swan to become an honest evocation of the intense anxieties and insecurities that come with expressing the full spectrum of the self. Patrick Devitt

Bell House is full of details at once quotidian and poignant: a neighbor’s neglected dog in “Take the Doggie,” which the narrator secretly feeds and longs to rescue; and the childhood home in “Champion,” whose stairs become harder and harder for his mother to climb. These small observations are set to music that is rich and ornate — and which has spurred frequent comparisons to the Beach Boys. But Shy Boys’ music goes beyond the expected choirboy vocal harmonies and transcends the instrumental and textural tropes of most would-be Brian Wilson imitators. Evincing a deeply intuitive relationship with Wilson’s writing, the band’s vocal melodies wend ever upwards in unexpected and harmonically defiant ways. Their music is suffused with a similar loneliness and yearning, and their harmonies have the same prayer-like desire for a deeper communion with the world around them. The coexistence of that prettiness (and its impression of the heavenly) within the small world of these songs is what makes Bell House such a stunning record. The songs hint at the depths of feeling within the smallness of lived experience, demonstrating our endless capacity for making sense of our surroundings. Miguel Gallego

εὐδαιμονία – Retrospective Release

Unlike Springsteen’s previous albums, there is no glamour in Nebraska. There are no bombastic rock anthems, nor romantic crowd pleasers. Here, his music is sparse — mainly acoustic guitar, harmonica, and that passionate, recognizable vocal. Through this minimalistic approach, Bruce delivers his opus: a sprawling and poetic work on the plights of farmers, factory workers, gas station attendants, cops, and criminals, all caught in a cycle of perpetual darkness. Never has Springsteen’s talent as an impressionistic lyricist been more on display. He implores us to empathize with the characters in his songs — to reflect on how they got here and what their salvation might be. Nebraska harshly critiques American culture, yet never damns it. Instead, the album seeks to find our common humanity, and in doing so, transcends its time and medium. George McCann

Comments are closed.