For Orson Welles aficionados, the director’s incomplete films have long been viewed as a kind of elusive dream — a parallel body of work to his official releases, which themselves have been distorted by various forces. Within this phantom oeuvre, Welles’s The Other Side of the Wind is the most tantalizing prospect. This is largely because Jonathan Rosenbaum and Peter Bogdanovich and Gary Graver and Joseph McBride have been talking about the film for so long that it’s come to feel as if it’s always right on the precipice of a full-fledged existence. And now, thanks to Netflix’s financial backing, The Other Side of the Wind has completed that passage, entering into Welles’s official canon of releases. What a strange, unexpected gift for 2018 to bring: A ‘new’ Welles film, some thirty years after his death, bearing all of its tortured history for us to grapple with.

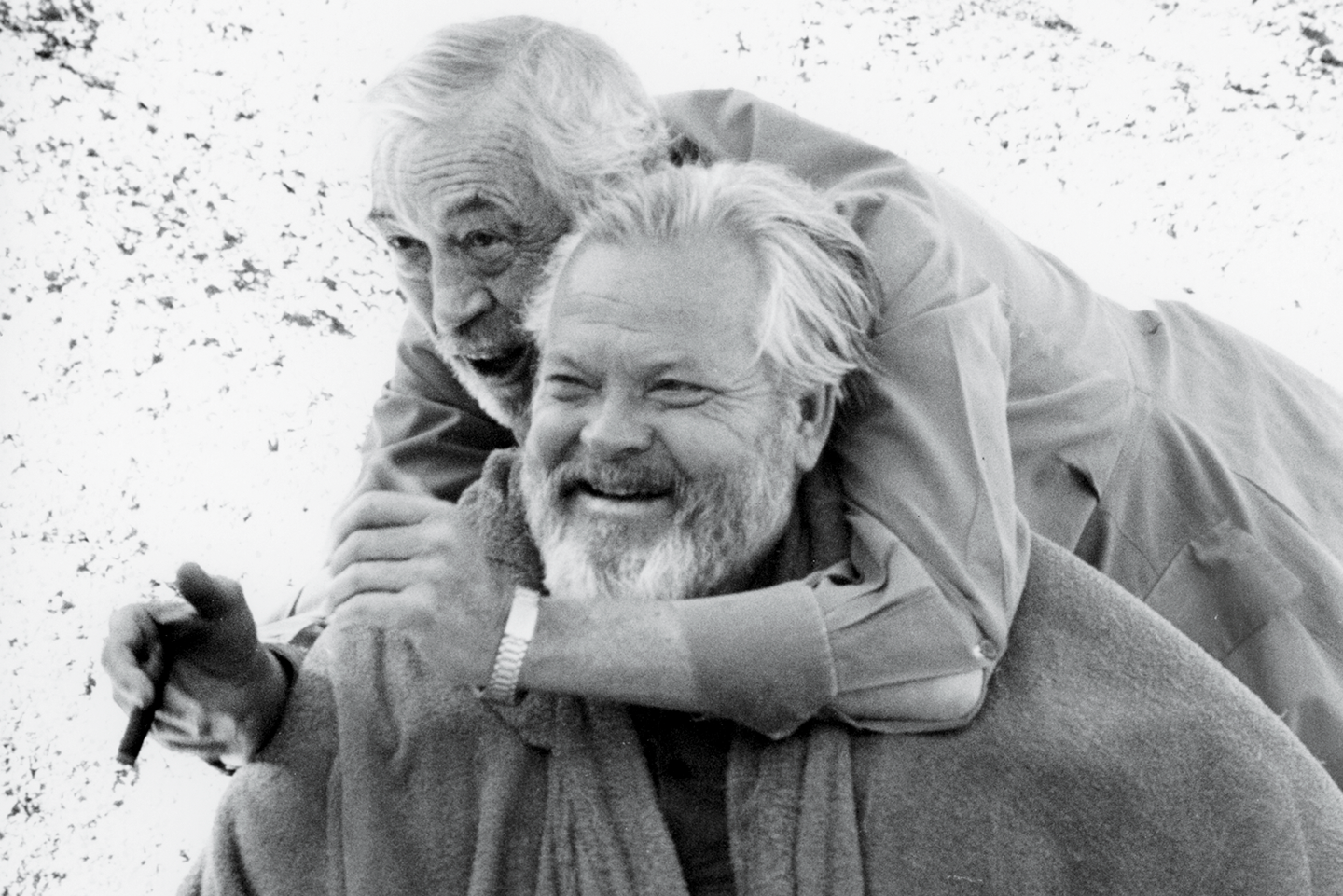

Whatever experimental and discursive elements employed here, though — and there are many — The Other Side of the Wind does have a proper narrative. Legendary fictional director Jake Hannaford (John Huston) is putting on a party, inviting anyone and everyone to a bacchanal and screening of his latest picture, also called The Other Side of the Wind — a European art-film pastiche that he hopes will put him back on top. But Hannaford has run out of money, he has no support from the studio producing his film, and he has seemingly lost his leading man, John Dale (played by the perfectly named Robert Random). Protégé and rising star Brooks Otterlake (Peter Bogdonavich) is also along for the ride, and the young upstart constantly reminds Hannaford of his increasing age and decreasing directorial prowess. Of course, in a fractured fun-house mirror kind of way, the relationship between Hannaford and Otterlake almost perfectly matches that between Welles and Bogdanovich in real life: During the prolonged production of Welles’s The Other Side of the Wind, Bogdanovich would direct The Last Picture Show, graduating from adoring Welles fan to a commercial force in his own right (and certainly an artist of more commercial success than Welles ever knew).

The film is just crammed to the breaking point with stuff, a wholly unique work in Welles oeuvre, yet one that also, somehow, fits snuggly next to Citizen Kane (it begins with a death) and the Shakespeare films (Huston’s Hannaford is ultimately as pathetic as Welles’ own interpretation of Falstaff), and even Mr. Arkadin.

At Hannaford’s party, multiple cameras document the director and his entourage, freely mixing color, black and white, 16mm, and 35mm film stock. Meanwhile, the film-within-a-film that Hannaford screens, in pieces, is shown to be shot in full color and in widescreen. It’s a fascinating contrast: Welles’s film is violently kinetic and aggressively verbose, while Hannaford’s generally exudes a surface calm, moves at an elliptical, leisurely pace, and is blatantly, unashamedly sexual (a departure from every other film that Welles ever made). The whole enterprise is, of course, meta as hell, a movie experience seemingly held together with scotch tape, the stability of the image holding on by a thread. Welles’s The Other Side of the Wind is an agitated (and agitating) film, its barrage of edits leaving images to slam into each other precariously, as if the projector might explode at any moment. Every line of dialogue is a bon mot, an innuendo, men of power playing games and having dick measuring contests. Welles is trying to encapsulate 50 years of Hollywood history and misery and his own excommunication into the overlapping dialogue, a kind of last will and testament on the state of Hollywood as he knew it.

Welles’s editing (or maybe more accurately Bob Murawski’s approximation of it) cuts mercilessly between seemingly dozens of cameras, covering the same short scene from every possible angle, cutting on dialogue, cutting to observers and through all kinds of visual bric-a-brac. It’s also a series of amateur roman a clefs, with thinly veiled caricatures of Pauline Kael, Robert Evans, and even Bogdanovich’s then-real life girlfriend, Cybill Shepard. There are weird psychosexual power struggles, and at one point there are midgets running around setting off fireworks. The film is just crammed to the breaking point with stuff, a wholly unique work in Welles oeuvre, yet one that also, somehow, fits snuggly next to Citizen Kane (it begins with a death) and the Shakespeare films (Huston’s Hannaford is ultimately as pathetic as Welles’ own interpretation of Falstaff), and even Mr. Arkadin. The Other Side of the Wind is obsessed with power and death, it reveals secret histories and labyrinthine pasts, and it freely mixes fact and fiction. Welles was the ultimate bullshitter, hence his love of magic and sleight of hand. He made an entire film about tricking audiences, conning them, and it’s perhaps the most playful, joyous thing he ever made. In a sense, The Other Side of the Wind is the dark side of F for Fake. It’s an absolutely impossible film, so frustrating and, of course, so fascinating.

To accompany the event-release of Welles’s The Other Side of the Wind, Netflix commissioned a couple of supplementary features. The most prominent of these is Morgan Neville’s feature-length documentary, They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead, which attempts to detail the production history of The Other Side of the Wind, while also delving into Welles’s personal life. It’s a mixed bag, offering a useful primer for anyone not already intimately familiar with Welles, but also regurgitating some of the worst preconceived notions about his career. Just for starters, Neville perpetuates the myth that it was all downhill after Citizen Kane and that Welles would never live up to that promise again. As Jonathan Rosenbaum has written about extensively, this is a lazy shorthand for refusing to deal with Welles’s work; in the essays “Orson Welles as Ideological Challenge” and “The Battle Over Orson Welles,” he writes that many regarded Welles as “an unsuccessful studio employee throughout his career rather than as an independent filmmaker,” which goes hand-in-hand with the “reading of Citizen Kane as a Hollywood picture, rather than the first feature of an independent filmmaker that happens to use certain Hollywood resources.” Neville also can’t help but comment on Welles’s weight in his later years, perpetuating an offensive parallel between obesity and some kind of slovenliness and/or laziness. They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead also presents a dubious timeline of Welles’s later career, giving the impression that The Other Side of the Wind was in constant production instead of the reality of a stop-start continuity. While the documentary does introduce some of Welles’s late projects, it doesn’t do enough to show how these were in production simultaneously with The Other Side of the Wind — and juggling multiple projects was always Welles’s preferred working method. Lastly, Neville seems to buy into the the myth that Welles ‘abandoned’ The Magnificent Ambersons to go begin shooting It’s All True in Brazil, whereas both Rosenbaum’s essay “Truth and Consequence” and Bill Krohn’s work on the documentary It’s All True: Based on an Unfinished Film by Orson Welles put that theory to rest years ago with ample evidence that the stories RKO Pictures concocted were both politically and racially motivated. (Welles was spending too much time celebrating the poor working class and filming jangadeiros.) Ultimately, They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead seems stuck between venerating Welles as a genius and setting him up as a figure to be cheaply psychoanalyzed and mocked. Nonetheless, there is some modest value to the film: in particular its back-story and wealth of never-before-seen footage. We get a lengthier scenes of Dennis Hopper, and a longer glimpses of Claude Chabrol, Curtis Harrington, Henry Jaglom, and Paul Mazursky, all of whom have blink-and-you’ll-miss-them cameo appearances in The Other Side of the Wind. They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead also properly respects Oja Kodar as an artistic collaborator to Welles, not just an actress/girlfriend, and devotes some time to Gary Graver, the cameraman who shot almost all of Welles’s work for the last fifteen years of his life.

Neville’s film seems to buy into the the myth that Welles ‘abandoned’ The Magnificent Ambersons to go begin shooting It’s All True in Brazil, while both Rosenbaum’s essay “Truth and Consequence” and Bill Krohn’s work on the documentary It’s All True: Based on an Unfinished Film by Orson Welles put that theory to rest years ago.

The other Netflix commissioned supplementary work is, strangely, only listed as a trailer for The Other Side of the Wind — and also doesn’t appear to be a separate, searchable item on the service. But the Ryan Suffern-directed A Final Cut for Orson: 40 Years in the Making is, in fact, a full 40 minutes, and it’s worth digging around to find, even if it’s a little dry. The film gives a much more detailed account of the actual process of acquiring the original materials for The Other Side of the Wind and what kind of work was required to put all these materials into a shape that could be edited into a proper feature. The mountains of film stock that were shipped from France to California boggle the mind, as do the accounts of matching the work print elements to the stored original footage and sound recordings (which comprise their own mountain of reels). Contrary to the lame pontificating of They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead, and its assertion that Welles wouldn’t finish films, A Final Cut for Orson suggests that it might very well have been literally impossible for Welles to finish The Other Side of the Wind without the benefits of modern technology. In one fascinating section, a technician uses a proprietary A.I. program to compare 2 trillion frames between a work print and the original negative. A Final Cut for Orson also shows Michel Legrand composing the score for the finished film, as well as some digital effects created by ILM to finish several scenes that Welles never shot. There’s also footage of Danny Huston in a recording booth doing ADR for his father John’s role as Hannaford, which is a bizarre bit of Borges-ian mindfuckery. A Final Cut for Orson is a joyful document that follows talented technicians who exude a genuine excitement over having been given the opportunity to work with this footage, and who do their level best to honor Welles’s wishes wherever possible.

You can stream Orson Welles’s The Other Side of the Wind, Morgan Neville’s They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead & Ryan Suffern’s A Final Cut for Orson: 40 Years in the Making (“Trailers and More”) on Netflix.

Comments are closed.