Tseden’s latest is a clever indictment of the ways that both religion and government seek to deny women their due agency.

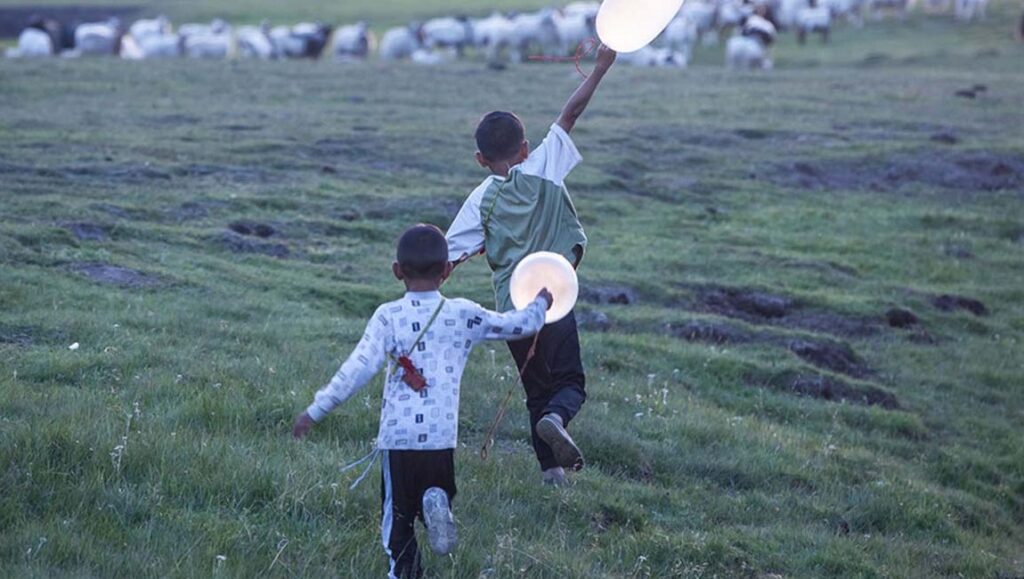

Tibetan director Pema Tseden’s artistic intention, in both his films and short stories, has been to realistically depict the daily lives of Tibetans, without the exoticizing lens employed by others who’ve made films about them — especially those made by non-Tibetans. Balloon continues this mission, with a potent yet subtle streak of surrealism and mysticism. The film is set in the early 1980s, shortly after China imposed its one-child policy (which was slightly relaxed for ethnic minorities, such as Tibetans), including stiff fines for violators of the policy. This is the historical backdrop through which we view the lives of a rural Tibetan family of farmers. Dargye (Jinpa) and his wife Drolkar (Sonam Wangmo) live with Dargye’s father and their two rambunctious young sons, whose playful acts of mischief play a large role in driving this narrative. Initial scenes often play as a subtly droll sex comedy, as the kids play with “balloons” (which turn out to be actually blown-up condoms given to their parents by the local clinic for family planning).

Dargye has a very pronounced sex drive — he’s jokingly compared to the rams he herds for a living — which causes potential financial danger for the family, as he must be careful not to get his wife pregnant again, lest he incur a fine. His boys, who continually find hidden condoms, cause all sorts of trouble for the family, who live in a very conservative and easily scandalized rural Tibetan community. (Much humor is mined from the fact that the farm animals have far more sexual freedom than the humans who raise them.) A more serious subplot concerning Drolkar’s sister (Yangshik Tso), now a Buddhist nun, serves as counterpoint. She runs into her old lover (Kunde), whose perceived mistreatment drove her to the monastery, and he gives her a novel that he wrote, which was inspired by their relationship, hoping to clear up, in his words, a “misunderstanding” about what happened between them. Tseden relates this beautifully told tale through intimate, expressive camerawork, vivid depictions of the dreams and visions of its characters, and vibrant performances by actors who exhibit the authenticity of non-professionals — even though they mostly aren’t. The Tibetan Buddhist belief in reincarnation figures largely in this story, and Tseden cleverly connects this with China’s state-imposed family planning to deliver an unstated, but unmistakable, indictment of the ways religious beliefs and authoritarian governments collude to deny women control of their own bodies and destinies.

Published as part of February 2020’s Before We Vanish.

Comments are closed.