He Thought He Died

Before He Thought He Died (2023), a friend spoke on his misgivings about 88:88 (2016), Isaiah Medina’s hitherto best-known film, echoing sentiments that sounded familiar. He remarked that the film’s reflection on poverty was ironic, given that its reliance on academic language rendered it inaccessible to the majority of people, and thus, the majority of poor people. Striding ebulliently on stage and ending our conversation, Medina opted for a brief introduction of his latest film: “I don’t have much to say, because I don’t think cinema is a linguistic medium.”

Medina makes film as film criticism, somewhat obviating the written word, much less the festival dispatch, as a viable path into his own work. Nevertheless, a spare plot synopsis is in order to suggest the film’s shape, and introduce some thematic concerns. He Thought He Died is about two characters. The first, a painter portrayed by Medina, stages a heist of his paintings from an art museum. The second, a filmmaker portrayed by Kelley Dong, a fellow director and critic, is shooting a film in that same museum. This skeletal action is interspersed with dialogues in hotel rooms on subjects like film form, aesthetics, and morality. To judge from the timing of the film’s not insignificant amount of walkouts, it’s these dialogues that prove to be the breaking point for audiences.

Before arriving there, however, it would do well to enumerate Medina’s exhilarating formal approach. Few filmmakers have adapted Kuleshov’s doctrine to the digital age with such rigor. Phil Coldiron, Medina’s greatest interpreter, noted that Inventing the Future (2020), which is available for free download on the Quantity Cinema website, almost begs to be dropped into a digital editing suite to be fully perceived. The most salient quality of Medina’s sequences is their density: of image and meaning. They strain the bounds of what an audience can perceive in real time. He Thought He Died actually decelerates this breathless pace, to an extent. In the new film, the 24 frames per second dogma is stretched graphically, as well as temporally. Desktop screens, GUIs, camera displays, and four-quadrant canvas frames subdivide nearly all of the images in He Thought He Died. This fracturing principle is accentuated by the subject of much of the film’s visual attention: the daily work of art conservation underwent by Medina’s character’s paintings at the museum. We hear the snap of latex gloves, the masking tape, the specially fitted bits of styrofoam, and the scanning of barcodes, each essential to sealing art away.

Turning to the dialogues, there would then seem to be a contradiction between a film concerned with art’s seclusion from society, and a film that prominently features the type of heady intellectual discourse likely to reinforce the most narrow-minded conceptions of inaccessible experimental cinema. Medina cuts between Dong and a conversation partner (Myles Taylor, Alexandre Galmard, and Andilib Khan, at different points), flickering the lighting and snapping to new perspectives as the speakers bounce maxims off one another. “The good is the master where evil’s close-up is located, and even if the master is not made, it is presupposed,” Dong says at one point. At another, Medina subtracts their words in favor of a section of composer Kieran Daly’s “Two Voice Ho – Ha – Hee Heterophony For Synthesized Speech 2022,” indicating that he’s not unaware of the dialogue’s potential for opacity.

For myself, taken in whole or part, these sections don’t coalesce, nor could I venture even a preliminary reading of some sort of overarching meaning that I could extract or synthesize in words. But certain snatches provoke flights of intrigue. “I can imagine a planetless art, but an artless planet is much more frightening,” stuck with me for much of the film. Preserving art for posterity entails the jettison of much of its context. To that end, the best sequence in He Thought He Died is an interruption of the film’s overarching sterility, when Medina pivots to a montage of home video clips stretching back over a decade, from his adolescence in Winnipeg through his college years at Concordia. The warm tide of pixelated camcorder footage suddenly reveals the close interdependence of art and context.

This is all to say, the gap between Medina’s scope and his audience, as remarked upon by that aforementioned friend, is not a blind spot for the filmmaker. Though his films can be unwieldy or even impenetrable, he seems to posit that art must belong to the world. He wants to reach people, and possibly even to be understood — it’s the reason he’s made nearly all of his work available for free on YouTube.

After the screening, another audience member asked Medina how he reconciles what he called the “non-linguistic” nature of cinema with his own films’ propensity for wordiness. He responded that speaking and being understood in language is a privilege, one that he, as a Filipino raised in Canada, has been denied for Tagalog. “People just want me to cut really fast,” he went on. “I refuse that. I want to speak, I want to think, in public.” Medina’s cinema can be approached as a language to learn. “All that is left is punctuation marks, not words,” Andilib Khan repeats in the hotel room, offering a provisional Bescherelle for the work. As with any language, the rules can appear arcane, or even rife with contradiction, but acquiring fluency can open new pathways in the brain of the patient and attentive learner. — DYLAN ADAMSON

Pain Hustlers

The suburban opioid crisis, like the war on terror and the ‘08 financial collapse before it, finally gets the smug “explainer video” treatment. After faintly respectable yet dull social dramas like Ben is Back, Beautiful Boy, and the miniseries Dopesick (not to mention documentaries like All the Beauty and the Bloodshed) softened the ground, this fall Netflix is releasing both their own “Big Pharma as callous death merchants” limited series Painkiller, as well as the feature film Pain Hustlers. The tone of both could aptly be described as “can you believe what these SOBs got away with?” exasperation over drug companies getting half your family strung out on pharmaceutical-grade narcotics. Directed by dutiful steward of the J. K. Rowling cinematic universe David Yates, and loosely inspired by the Insys Therapeutics scandal of the 2010s, Pain Hustlers explores the way a pharmaceutical startup was able to hook a large segment of the country on Fentanyl through a perverse incentive structure where people with ailments ranging from broken bones to migraines were prescribed highly-addictive pain medication meant for stage-4 cancer patients. Millions died of overdoses, the walls eventually came crashing down on the scheme, and the Feds rushed in to arrest everyone, yet the film insanely positions the entire sordid affair as the saga of a brave whistleblower standing up and doing the right thing. Sure, everyone got rich off of the suffering of others, which means the film gets to dwell on all the beachfront real estate, corporate retreats, designer clothes, and luxury cars, but at least somebody tried to do the right thing just before the bottom fell out. And isn’t that what really matters?

Emily Blunt plays Liza Drake, a Florida stripper so singularly unconvincing the film can’t be bothered to go through the motions of showing her perform during a shift. Living out of her sister’s garage, driving a car that belches black smoke, beefing with her ex, and trying to raise a delinquent tween daughter with a serious medical disorder, Liza is an unimaginative writer’s construct of what a desperate person looks like — all that’s missing is having her walk around in a wooden barrel. While at work Liza chats up yammering pharmaceutical rep Peter Brenner (Chris Evans). whose shadiness is telegraphed by his perma-five o’clock shadow goatee and unaddressed Boston accent (the actual case took place in Massachusetts, so this feels like a vestigial remnant of an earlier version of the film). After what we’re meant to believe is a couple of hours spent talking with Liza at the bar — you know, behavior sleazy strip clubs are totally cool with — a drunken Peter offers her a job to come work for him at the pharmaceutical firm, Zanna, despite her possessing no actual qualifications other than the highly desired, only-in-the-movies talent of knowing how to “read” people. It probably doesn’t hurt that she can fill out a low-cut blouse.

When Liza takes him up on his offer and shows up at the Zanna offices, she finds the company seemingly weeks away from bankruptcy and presided over by eccentric millionaire and company founder Dr. Jack Neel (Andy Garcia, inexplicably doing a wavering Foghorn Leghorn impersonation). Dr. Jack’s “miracle” Fentanyl spray, Lonafin, is stagnating in the market as doctors refuse to prescribe it. Despite being exponentially more effective than the competition, Lonafin has been frozen out as larger, better-funded pharmaceutical companies have most doctors already wrapped around their fingers, pushing their drugs instead. Told she has a week to “close a whale” (which is to say convince at least one outpatient doctor in her territory to prescribe Lonafin to an actual patient) or she’ll be fired, it appears as though Liza’s professional lifeline is more of a noose. Yet through gumption, persistence, and screenwriting contrivance, Liza finally convinces a suitably unscrupulous doctor (Brian D’Arcy James) to play ball, and faster than you can say “side effects may include,” she’s off to the races.

Pain Hustlers primarily deals with the practice of “speaker programs” where doctors are paid to evangelize medication to other doctors, typically at all-expenses-paid corporate getaways, a technically legally but closely monitored, potentially unethical practice. Cutting corners to save money and avert the notice of federal regulators, Liza and Peter begin to run speaking tours around the Southeast, which, along with kickbacks and outright bribes (there’s an especially egregious Omaha Steaks product placement in the film), allows Zanna to thrive — and Liza with it. Cut to Semisonic’s “Closing Time,” and we watch as Liza elbows aside the competition, rolling up dozens of doctors, clinics, and pill shops while the numbers on her checks go up. Seemingly every day is a party of backslapping and “ain’t I a stinker” smirks. Soon, Liza’s traded in her sister’s garage for a condo overlooking the Gulf of Mexico, is pulling down a six-figure salary (and millions in stock options only months away from vesting), and even hires on her mother (Catherine O’Hara, appearing to be enjoying herself wearing mini-skirts and knee-length boots) alongside a small army of former strippers, ex-beauty pageant contestants, and high school drop-outs in push-up bras to serve as sales reps. But success only breeds discontent, and once Dr. Jack starts demanding increased profits, it’s just a matter of time before Peter suggests they start paying doctors to push Lonafin “off label” (i.e, to treat ailments for which medication hasn’t been FDA-approved) to expand their market share, inadvertently creating a nation of addicts in the process.

Yates has semi-anonymously directed some of the most financially successful blockbusters of all time, but overseeing the “Wizarding World of Harry Potter” is a poor training ground for either a dense explication of corporate greed or a morally ambiguous adult drama. The film employs a quasi-documentary framing device that allows it to dump scads of expletive-laced exposition on the viewer, as well as inelegantly inserted, direct-address victim testimonials, only to abandon the device for so long one questions whether the filmmakers have simply forgotten about it. Pain Hustlers is positively riddled with incredulous plot devices and eye-rolling contrivances — to name but one example, much is made of how the increasingly paranoid Dr. Jack refuses to send texts or emails documenting his illegal activities, to the the point the film builds a minor heist into its third act so that Liza can retrieve an incriminating, hand-marked computer printout, only to later show the ultra-careful executive responding to an email from a sexual conquest where he signs off on malfeasance seemingly “just because” — which does little to reinforce the idea that we’re getting an insider’s account. Although based on Evan Hughes’ 2018 New York Times Magazine article, the extent to which this has been thoroughly researched feels limited to the filmmakers watching The Wolf of Wall Street through their fingers, speeding through most of the truly debauched behavior (it’s a curiously sex-less film with Blunt not even given a superficial love interest) and reducing a criminal conspiracy to something that feels like “pyramid schemes for beginners.” And then there is the genuinely baffling aesthetic decision to shoot the film with anamorphic lenses yet frame every single shot so that the dominant action takes place dead center in the middle of the widescreen frame. It all adds to the sensation that the film is an antiseptic-looking, underpopulated — though set in 2011, it might as well have been shot during Covid for how empty all the office spaces look — shoebox diorama entirely devoid of humanity.

But what genuinely rankles here is the entire conception of the Blunt character, an amalgamation of a handful of individuals where the film’s dearth of imagination and maturity feels especially insulting. Freed from any kind of obligation to honor a real person, the film still equivocates, presenting the character as relentless when it comes to venial sins like bribing doctors to boost her sales commissions and keeping regulators in the dark (“going 67 in a 65” as the characters are fond of saying), while drawing a difference with distinction as it pertains to mortal transgression like prescribing Lonafin off-label. Despite possessing all the killer instincts of her more seasoned colleagues and every bit the financial incentive they do to push the envelope — in an especially manipulative touch, we learn her daughter’s life-saving surgery will cost $400k, which she can neither afford nor secure a loan to pay for in spite of being a millionaire — the film repeatedly attempts to differentiate Liza from her unscrupulous coworkers; she’s only going along with this out of fear of financial ruin and concern for her daughter. Hers is the voice of dissent, reason, and compassion; the film even gives Liza a subplot where her former neighbor overdoses, allowing Blunt to sob and beg for forgiveness as his widow shuts the door in her face. Pain Hustlers is attempting to create an actual dichotomy of heroes and villains in the world of scummy pharmaceutical reps without ever acknowledging the character’s willful blindness to the effects of pushing a highly potent narcotic on the public. It’s all very “I’m shocked to find that gambling is going on in here” without the necessary compartmentalization or self-awareness required to make the character compelling — or, to quote one of the few non-quack doctors featured in the film, upon being told Lonafin might be habit-forming, “no shit, it’s Fentanyl.” The film addresses Liza’s legal exposure and ultimate culpability while still finding reason for her to hold her head high. So while it may be unfair to Yates, it’s too tempting not to equate this sort of simplistic approach with his nearly two decades directing films for children. The director wears the script’s glibness as uncomfortably as Pain Hustlers does his unearned faith in humanity. Truly, the worst of all worlds. — ANDREW DIGNAN

Snow Leopard

The late Chinese, Tibetan minority filmmaker Pema Tseden is no stranger to the Western international film festival circuit (which is also the case for many other films of similar ethnic specificity from the Middle Kingdom). This writer has enjoyed the opportunity to cover various prior films of this type within the setting, from Pema’s own Jinpa (2019 NYAFF) to the Inner Mongolia-set Anima (2021 NYAFF), and Snow Leopard — which received its North American premiere at this year’s TIFF — sits comfortably within the genre-specific framework that has established itself over time around the Chinese minority cinema model of production.

Pema Tseden, the first filmmaker of Tibetan ethnicity to graduate from the Beijing Film Academy, is in every sense a loss to domestic cinema of China, having worked steadily to promote the language, religious orientation, and socio-cultural mores of his minority within the country’s artistic landscape. In contrast to famed Tibetan-focused, Han-majority made films such as Tian Zhuangzhuang’s The Horse Thief, wonderful as it is, the attentiveness of non-Han minds and hands crafting this world and life for screen has long been of a sadly underseen but quite necessary input; which mid-2000s policies pleasantly began to encourage and commendably came more greatly to the fore in the 2010s.

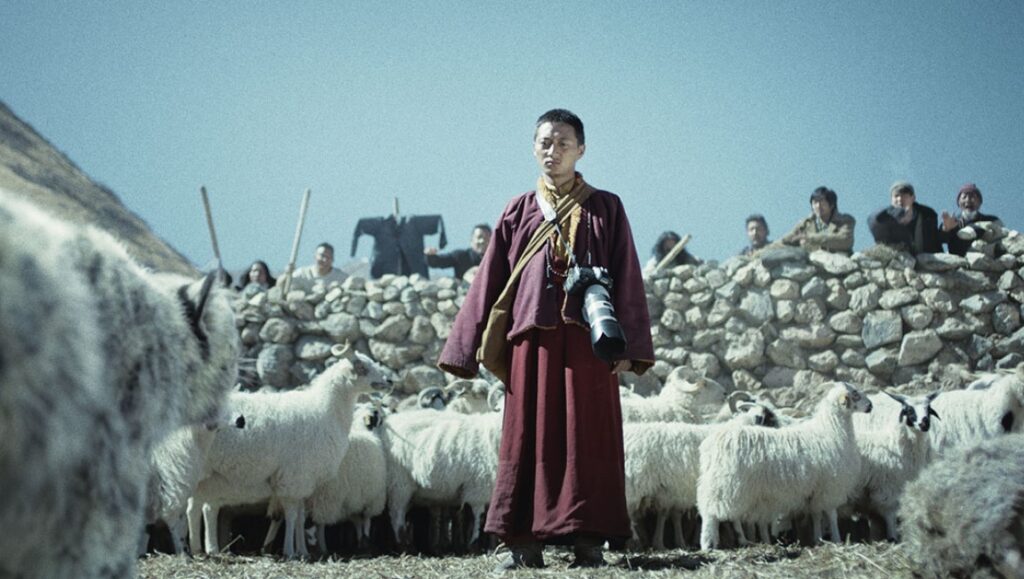

Snow Leopard, in line with Pema Tseden’s prior Balloon and Jinpa, among others, takes for its interests a commentary on Buddhist religious postures toward nature and bureaucratic and legal indifference for the fallout of animal protection policies on the lives of everyday people. The central dilemma is, unsurprisingly, centered around the titular big cat, one of which has broken into and found itself caught in a farming family’s sheep enclosure and, in a frenzy, killed nine rams. Within the family, two brothers lead the discussions over the fate of the animal. One, Jinpa (played by actor of the same name, Jinpa), insists on its death; the other, frequently referred to by his nickname the Snow Leopard Monk (Tseten Tashi), is adamant on its release. Throughout all this, a film crew is present and capturing the events in a muted, meta-textual manner, alongside a litany of local government and police officials who arrive to enforce release on the basis of law, meeting protest from Jinpa as he demands upfront compensation.

The sum all of this is somewhat ruminative and likely of curiosity for those interested in this trend of Mainland Chinese cinema, not least for the discursive approach it takes regarding environmental and legal ethoses and applications. However, in comparison to other entries within the model, and even those by the director himself, it struggles for a sense of motivated purpose beyond the notes it needs to hit — and even those fail to quite coalesce into a proper sense of identity owing to an undercooked script and the limits of location that provincializes the drama to such an extent that it risks inconsequentiality. Despite this, the film demonstrates its most powerful and unique touches in the stretches that explore the unlikely connection between the monk and the titular leopard. The effect here matches the power of Pema’s strongest moments in unlocking and presenting religious theory in visual language. However, unlike Jinpa‘s fusion of such things in a captivating genre mode, Snow Leopard is less capable of sustaining this due to the aforementioned pre-production limitations.

Nevertheless, Pema Tseden’s loss will be felt heavily within Chinese cinema going forward, yet his passing may not be yet mourned too heavily owing to, firstly, information suggesting that perhaps two other features were or are at varying stages of production still; while, secondly, the Buddhist outlook forwarded in his work underlines the samsaric cycle that may well take him and return him to the world in another life of some kind. With that said, as film viewers, there is every reason to be thankful for the works of the director that we have, and while Snow Leopard stands by no mean as a summative work, it’s in every sense an emblematic one, and every strength that need be seen is present for those who wish to offer this work attention. — MATT MCCRACKEN

100 Yards

Xu Haofeng makes movies for people who enjoy and understand the finer points of martial arts choreography. His best-known film work (he’s also a novelist) is probably the screenplay for Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster, in which Wing Chun master Ip Man navigates the various schools and styles of early 20th-century kung fu. Two of Xu’s earlier directorial efforts, The Sword Identity (2011) and Judge Archer (2012), have a strong cult following, although this writer hasn’t seen them. On the other hand, Xu’s The Final Master, which received a proper US release back in 2016, is a dour slog: the choreography is indeed unique, realistically fast and detailed, but the story of rival martial arts schools in pre-war Tianjin lacks dramatic sense, such that the action all blends into a rhythmically narcotic sameness.

Xu followed The Final Master with The Hidden Sword, which played a few festivals in 2017 and registered as a huge improvement over its predecessor — adding a satirical, comic flair that situated it closer to Jiang Wen’s films. Unfortunately, due to what are presumed to be censorship reasons, The Hidden Sword never got picked up for a proper release and appears to be, for the time being, staying completely buried. So now Xu is back with 100 Yards (co-directed with his brother, Xu Junfeng), which, like The Final Master, takes place in pre-war Tianjin (1920, to be specific). The film follows a succession struggle, with Shen An (Jacky Heung), the son of a recently deceased master, vying for control of his school against his father’s top pupil, Qi Quan (Andy On). The struggle draws in local hoodlums, the school being the guarantor of an uneasy peace — no fighting is allowed within a hundred-yard circle around it.

Heung is uniquely qualified for his role: The actor is the son of longtime producer and possible Triad associate Charles Heung, and previously starred in Johnnie To’s 2019 musical-action-comedy Chasing Dream, a performance and a film which were unjustly panned by many, regarded largely as To doing a favor for his producer. The Xu brothers’ casting of Heung as a nepo baby here, then, is actually pretty funny — but once again, the actor’s performance is good in its own right, too: Whereas in Chasing Dream, he’s all positive exuberance and wide smiles, here he internalizes everything, in keeping with the somber tone typical of a Xu Haofeng film.

Heung’s co-star, American-born Andy On, is likewise a good fit. While the actor — who was discovered by Charles Heung while working as a bartender in Rhode Island — has never really become a big star, he began his career with a one-two punch of off-beat auteur projects — Tsui Hark’s Black Mask II and Ringo Lam’s Looking for Mr. Perfect. He also starred alongside Scott Adkins in a bizarre and kind of fascinating straight-to-video John Carpenter pastiche from 2019 called Abduction. In 100 Yards, he’s terrific — relentlessly focused, with just a little bit of a flair for evil. His fight scenes with Heung are also very good; as a martial artist himself, Xu Haofeng emphasizes realism in his screen fights, the most notable thing about them being simply how fast they are. Movie choreographers usually slow down and punctuate the action, adopting techniques from various styles of Chinese opera in order to highlight the movements and skills of the actors. The Xu brothers, however, are content to show us action in wide shots, at something like normal speed, meaning it’s often too fast for the eye to follow.

Thankfully, unlike in The Final Master, the fights in 100 Yards are varied and well-motivated, and not just in terms of plotting — these guys need to have this fight because of this reason, all the terms, motivations, and goals set out clearly beforehand — but in their choreography, as well. The final half of the film is essentially one long fight extended through multiple locations, as Heung’s Shen faces off against a variety of opponents armed with a variety of different weapons. The fight hinges on Shen being forced to use weapons he’s unfamiliar with: a pair of short swords (or long knives, like the ones central to The Final Master). Over the course of the fight, we see Shen learn how to use the weapons and adapt them to different enemies and environments. The sequence is well-paced, with moments of rest and discussion interspersed here and there, such that it doesn’t feel as exhausting as one long fight would be. The Xu brothers give us, and Shen, time to reflect on strategy, and as a result, the filmmakers’ obvious knowledge and commitment to putting the martial arts on screen reaches a kind of pedagogical clarity last seen in the work of Lau Kar-leung.

Additionally, Xu retains some of that Jiang Wen tone he brought to The Hidden Sword. The overcast streets of his Tianjin, where everyone wears either earth tones or shades of gray, are brightened up by moments of absurdity and sly humor, often provided by Taiwanese actress Bea Hayden Kuo — best known for starring in the Tiny Times series and who is Heung’s real-life wife — as Shen’s love interest, Xia. Whether draping herself fashionably around Shen at a society ball or riding proudly on her bicycle as a newly appointed post officer in the French colonial city, Kuo’s Xia lends a cock-eyed whimsicality to what would otherwise have been a grim story of two men’s petty rivalries.

Kuo’s performance grounds what could have been an abstract film about theories of martial arts in a tangible historical reality, connecting Xia’s position as the illegitimate daughter of a European banker with the school’s precarious position in Republican-era China, lurching between colonial interests, local warlords and criminal gangs, and factional dissolution. It’s not quite as effective as Zhang Ziyi’s role as a synecdoche for the decline of traditional Chinese culture in the 20th century in The Grandmaster, but then the Xu brothers are not as romantic as Wong Kar-wai. Xu Haofeng has proven to be a realist, interested less in sweeping emotional generalizations than in mining the smallest details of (martial arts) performance and ritual to learn what such minutiae might say about the wider processes of history and the relationships between people. 100 Yards strikes the perfect balance between choreography and plot, intrigue and satire, and it’s one of the best Chinese-language films of the year. — SEAN GILMAN

Poolman

In light of the ongoing SAG strikes, this year’s TIFF featured a bevy of actor-directors, (generationally) ranging from Michael Keaton to Finn Wolfhard — allowing both festival and filmmakers to dodge scab accusations or an ethics breach. One such director was Chris Pine, who skipped this year’s festival altogether, despite debuting his first directorial feature, Poolman. Filled to the brim with a plastic slacker charm and the referentiality of a high-school script with a first-time reading of Pynchon plastered all over it, Poolman boasts only one definitive claim to success: garnering the most walkouts. Co-starring Annette Bening (reading Karl Ove Knausgård), Danny Devito, and Jennifer Jason Leigh, the film follows a scatterbrained poolman named Darren Barrenman (Pine), who is trying to save Los Angeles from becoming one long bulldozed parking lot. He repeatedly goes to his psychoanalyst neighbor Diane (Bening) for life advice, while filming a documentary about his advocacy work with her husband, Jack (Devito), a talented but steadfastly unemployed filmmaker. Meanwhile, Darren immediately finds himself at odds with city councilman Stephen Tobolowsky (played by… Tobolowsky) and is embroiled in a water scandal that is comprehensible only insofar as Chinatown is repeatedly referenced to explain why a lack of water would be a problem at all.

So little time is spent on the actual context — in fact, members at the press screening were initially confused as to whether the film takes place in the 1970s or in the present day — that it isn’t even made clear that there is a drought at all, and especially not to any degree that would generate the dramatic tension necessary to guide the film forward. No, despite the geographic specificity of Poolman, the only thing distinctive about it is the pronounced slacker-comedy register adopted by Pine and his co-writer Ian Gotler, which generally revolves around a shallow, quick-pitched style of dialogue that has the dramatic and comedic nutritional value of a pack of mini-marshmallows. Superficially, it recalls something like The Nice Guys, but in place of Ryan Gosling’s effortless, quick-witted charm, the audience is left with a performance more reminiscent of Owen Wilson’s persistent whining in Midnight in Paris; there’s nothing here to effectively pull viewers into the drainpipe vortex of the film’s plot.

The nonsensical and inert mystery of Poolman is less akin to the noir charm of Chinatown (which some critics have somehow likened it to) than it is to Under the Silver Lake in its pothead-philosophy-bro’s bewildering sensibility to suggest intrigue without exploring anything with any depth. But then, even David Robert Mitchell’s work had more to offer; in that film’s moments of absolute incomprehensibility, there was at least a visual uncanniness and Pynchonian freedom of spirit that differentiated the movie from the benign forgettability of Poolman. Still, for all its shortcomings, Pine’s debut does provide a warm snapshot of Los Angeles, as he succeeds in imbuing the film with an appealing natural nostalgia, aided by his decision to shoot on film — so sad is the current state of filmmaking and its desert of originality that this decision alone is worth crediting. But ultimately, whether it’s the sun, chlorine, or weed, Pine seems entirely oblivious to just how shallow and superficially affected his first feature ends up being. — CONOR TRUAX

Working Class Goes to Hell

Set in a small Balkan town still reeling from a tragic factory fire several years earlier, Mladen Djordjevic’s Working Class Goes to Hell finds a local community combating ruthless capitalism with a decidedly creative solution: Satanic worship. Labor organizer and de facto den mother to a cadre of sour-faced ex-coworkers, Ceca (Tamara Krcunović) coordinates protests and petitions the courts on behalf of the dozen factory employees — including her late husband — who died in what was essentially a preventable industrial accident, but she’s failed to generate justice or anything close to compensatory damages. Adding insult to injury, the renovated and soon to reopen factory was promptly privatized, freezing out the existing workforce and thus decimating the local economy — the only two employers in town are narrowed to a sad tavern and a new brothel being run by a small-time gangster who happens to be tight with the mayor. Once new recruit Mija (Leon Lučev) starts attending the union meetings, discussions of legal strategies and public pressure campaigns begin to fall by the wayside, replaced by incantations, seances, and rumors that he converses with the dead. If Mija is truly able to channel the dark arts to connect with the great beyond, so the thinking goes, perhaps then he can conjure something that will serve as a vessel for the union’s vengeance.

With a title like Working Class Goes to Hell, there’s quite a bit to live up to, even by gonzo Midnight Madness standards, and it would seem that the film is paying homage to Elio Petri’s 1972 Cannes winner, The Working Class Goes to Heaven. However, what the former most resembles, curiously enough, is the long-running comedy series It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia (one can easily imagine the title in that show’s instantly recognizable white font-over-black background), not least because of how much both works hinge upon wilful misunderstandings, harebrained schemes, and reckless leaps to conclusions. After Mija begins to promote the all-encompassing powers of a vaguely defined yet emphatically not-God figure — the sort that allegedly responds to blood sacrifices, pagan symbols, and pentagrams drawn on the floor — the townsfolk begin to attribute all manner of signs and wonders to this dark entity — which appears to have taken the physical form of a golem-like mute who may have risen from the dead. Or perhaps he’s simply an alcoholic vagabond easily provoked to commit violence on their behalf. Either way, why look a gift horse in the mouth?

Djordjevic’s film presents its characters as proud ex-communists hardened by a difficult life (everyone in the film looks about twenty years older than their actual age) yet fundamentally unserious. They’re all consumed with the petty grievances and delusions of a better life while half their labor meetings are spent gathered around watching trashy reality TV. The union members abandon their understandable skepticism of the supernatural based on the most specious of logics, treating coincidences as an excuse to double down on their Satanic worship; it’s the sort of film where you can track everyone’s level of devotion by how willing they are to get completely naked for their prayer circles. It also becomes apparent to the audience rather quickly, if not to the other characters, that Mija is at best a shameless opportunist and more likely than not completely full of shit. Using his newfound stature to seduce Ceca, Mija then convinces her to prostitute herself (allegedly to appease their favorite deity), only to turn around and borrow money from her for “essential ceremonial expenses.” The film has no love for the heartless industrialists, the ineffectual courts, the callous gangsters (who recruit sex workers from the local population and force young women to act as nude food platters requiring regular “refrigeration”), or the corrupt politicians, but it arguably saves its most withering scorn for the proletariat who are seen to be almost child-like in their behavior and squabbling; the invocation of the spiritual world serves as the flimsiest of pretexts to act upon their most base and homicidal instincts.

For all its intriguing ingredients, Working Class Goes to Hell is ultimately a bit of a flavorless stew of unfocused resentment and glancing social commentary; its cardinal sin, however, is that it meanders toward an all but preordained violent conclusion. Djordjevic is juggling a handful of discordant tones — including social realism, pitch-black satire, melodrama, and supernatural horror — but they don’t inform one another so much as exist as self-contained modules: jump scares standing alongside pratfalls alongside the capricious death of innocents alongside relitigating the Yugoslav Wars, and so on. In addition to this whiplash, there’s little sense of escalation to the horror or buildup to the film’s pitiless final punchline. If Working Class Goes to Hell posits that desperation and hopelessness breed gullibility, it remains unclear whether it’s even attempting to equate Satanism with all manners of organized religion, and, if so, it doesn’t put the actual legwork in. The film’s rage is as undeniable as it is universal, but it remains inchoate and scattershot. — ANDREW DIGNAN

Yellow Bus

Sometimes people die for no reason, and that a tragedy can be so banal makes it all the more incomprehensible. This is what the immigrant family in Yellow Bus have to deal with, when one of their daughters is accidentally left trapped on an aging school bus in the brutal desert heat of the United Arab Emirates. First-time feature director Wendy Bednarz is also unable to reckon with this tragedy, in her own way, as she here grabs any shorthand for grief she can and holds it as close as Ananda (Tannishtha Chatterjee) holds the ashes of her daughter Anju, which she literally carries with her wherever she goes. In Yellow Bus, this complicated, unimaginable experience is flattened into tropes, into crying in the shower and seeing visions, as if stitched entirely from other movies, or, at best, based on assumptions of what it might be like to go through something like this. If it comes from Bednarz’s experiences, or the experiences of someone she knows, then it’s only more tragic to see them warped into something entirely abstracted from reality, and fit into such a basic template of festival-friendly realism. Unsurprisingly, much of Yellow Bus is shot in handheld close-ups with a shallow depth of field, a tired and entirely reified style desperate to convey the impression of truth. Meanwhile, the characters spend the film’s opening scenes mechanically establishing themselves, performing rather than living their relationships. It’s almost like Bednarz is in a rush to get to, and then past, the tragedy she chooses not to show (although she doesn’t quite resist portending it heavily). But that leaves the film, only fifteen minutes in, without anywhere to go. All it can do is shuffle these tropes of trauma.

Yellow Bus only starts to find its direction when Ananda chances upon some hint of foul play, when she’s given a chance to believe that Anju’s death might not have been so random and pointless. This might seem like a betrayal of the film’s central question, dissolving it into a more conventional mystery with a clear answer, and to some extent it is, but it does speak to the way many parents cope with the death of their child by directing their pain into a fight for justice. It’s obviously a deeply understandable and often noble thing to do, but it’s hard not to wonder if keeping a trauma so fresh for so long can ever end in personal resolution. Ananda, however, pretty straightforwardly pushes people away and deepens her family’s wounds. She’s much more driven by simple revenge than justice, because she never sees much beyond her daughter. This too is understandable, but it reaches such melodramatic heights in Yellow Bus that when she’s shoddily wrapping a package, you could almost believe it was a pipe bomb to send to Anju’s headteacher. The film pushes her right up to the edges of likability, especially when she tries to make love to her blandly kind husband (Amit Sial) after finding out that Anju might still have been breathing when she was found. The psychological portrait hardly rings true in this register of intensity, and it creates an uncomfortable friction with the film’s realist style, but it’s at least more challenging than the formal and thematic ambivalence surrounding it.

But that peters out soon enough, as anything interesting Bednarz hits upon comes only part and parcel with a blind flurry of other half-ideas. She can’t decide, either in script or direction, if Ananda’s investigation was justified; our heroine finds some genuine wrongdoing, but then suddenly forgives the person she thinks is responsible. Or if she went too far with her family, she almost seems vindicated when, in quick succession, her daughter and husband apologize to her. This kind of trauma, and the complications that arise from and entangle with it, are messy, but the film is not. All of its ambiguities and contradictions are flattened into a neat and comforting ending — where the family, quite literally, sees the light at the end of the tunnel — revealing them as another part of the sloppiness that defines the production, all the way down to the often choppy and amateur editing. Yellow Bus isn’t over-determined in the way many first features are because its intent is too fuzzy and unsure. These are not ideas that are as yet unformed, but rather ones that seem to lack a vision altogether. — ESMÉ HOLDEN

Comments are closed.