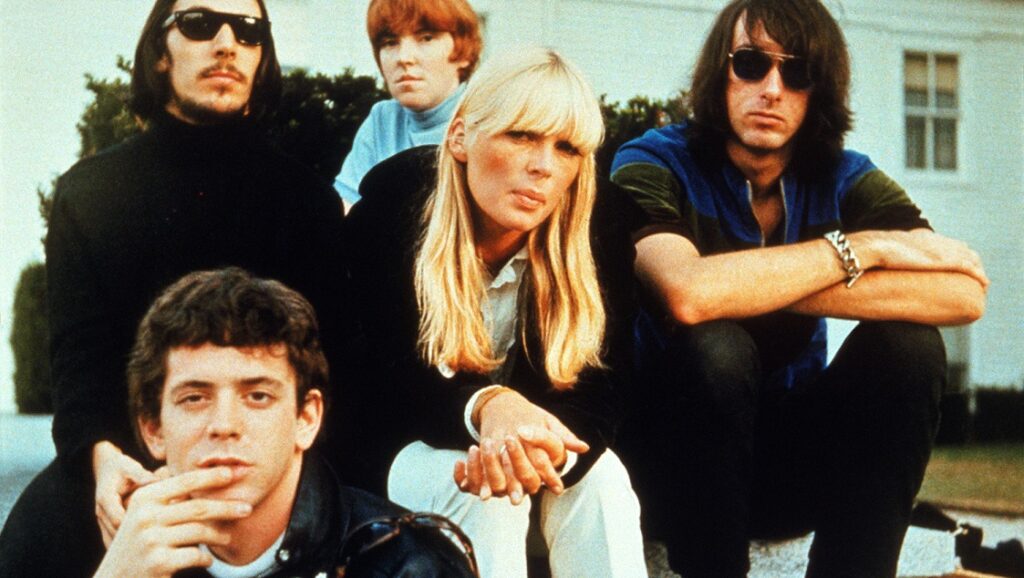

The origins of The Velvet Underground as a group are about as haphazard as they come. The ostensible writer of the outfit, college-educated Lou Reed, seemed as entranced by the literary realism of his creative writing professor (esteemed poet and novelist Delmore Schwartz) as he was enamored with the three-chord rock ditty. While working as a hired gun for Pickwick Records, Reed fortuitously met a visiting John Cale, acolyte of John Cage’s loops and La Monte Young’s drones. Reed also connected with Sterling Morrison, a fellow Syracuse alum and native Long Islander who liked Reed’s and Cale’s idea of a rock composition built around one sustained tone — an idea that had already been brought to the avant-garde by Young (e.g. “#7” from Compositions 1960, which includes the instruction, “To be held for a long time”). Finally, the band recruited Maureen “Moe” Tucker, the sister of one of Morrison’s friends and — more importantly, after the sudden departure of original drummer Angus MacLise — the owner of a much-needed drum set on the eve of an all-important high school gig. Thus, the classic lineup came together; but shortly after that, the Velvets were ‘discovered’ by Andy Warhol’s posse, and the mercurial artist became their manager and mentor. Warhol also insisted that the band make one of his “stars” its frontwoman, although Nico — actress, model, chanteuse — wasn’t even his first choice! Nevertheless, Nico and every other member of the Velvets represent one part of what made late-’60s rock an indelible, mind-expanding phenomena; each comes from a different strain of music and culture, and each democratically brought their take on quintessentially 1960s music — before said music became immortalized, arguably corporatized, and moreover, mythologized. Before there was a “purpose” for rock — for better or worse — the Velvets defined that purpose, laying the groundwork for both the punks, and the new wave.

“Run, Run, Run” starts as a would-be Chuck Berry groove, or a mockery of the Beach Boys (with hilariously awful harmonies), before it snaps into some variation of surf rock for a ripping guitar solo.

On the surface, The Velvet Underground & Nico seems to flow from Reed’s Pickwick recordings, furthering his desire to “elevate the rock song” by embedding within it a sense of realism. “I’m waiting for my man / Twenty-six dollars in my hand” is a lyric that renders a hilarious scene of a hurried smack purchase, one set to a driving, boogie-woogie instrumental. But that song noticeably clashes with the sentimentality of the previous track and album opener, “Sunday Morning,” with its gentle bass and arpeggiated celesta. These two competing impulses occasionally meet each other halfway: Nico’s first appearance on the album, “Femme Fatale,” finds the singer both saccharine and barbed, and that combination — paired with Reed’s terse lyricism — helps the song’s lovey-dovey pop arrangement also sell itself as a prostitute’s teasing leer. Generally, though, the tracks here — and the order in which they’re arranged — are deliberately discursive: “Run, Run, Run” starts as a would-be Chuck Berry groove, or a mockery of the Beach Boys (with hilariously awful harmonies), before it snaps into some variation of surf rock for a ripping guitar solo; “Black Angel’s Death Song” is a pioneering piece for the noise genre, and one that got the Velvets axed as Cafe Bizarre’s house band; “I’ll Be Your Mirror” is a delicate — if also slightly puzzling — ode to Warhol and his insistence on an art that’s “all surface.” Only on “Venus in Furs” do Reed’s erudite literary interests and Cale’s avant-garde firebrand musicianship achieve the closest thing to a coalescence. Moe Tucker’s primal bass-bass-tambourine beat seems to move in slow motion as Reed’s off-tuning and Cale’s electric viola shrieks recall some strain of Indian raga — all conjuring a vision of sadomasochism, not from the streets but the song’s namesake, a novella by Austrian humanist Leopold Von Sacher-Masoch. “Venus in Furs” is the decadent, multicultural plurality of voices with which rock music was about to become capable of speaking. But the “text” of rock music wouldn’t be what it is today without another major song here: “Heroin,” which is less an ode to addiction than a third-person exorcism, written by Reed; it becomes experiential, with Moe’s bass drum-as-beating heart voicing the user, Reed’s nonsensical-cum-orgiastic lyricism, and the controlled chaos of the band’s ebb and flow into atonal discordance. Like the rest of this album, it’s all frightening and deeply affecting — and it brashly redefined what rock music could be.

Part of Kicking the Canon – The Album Canon.

Comments are closed.