Peninsula is admittedly better than most recent zombie fare, but is reflective of an overall cinematic failure to innovate the genre.

The zombie film is, at this point, a cinematic staple. Given the sheer number of zombie narratives over the past decade, any qualitative assessment is sure to vary from person to person, the obvious highs and lows of the genre becoming less distinct amid the saturation. For film enthusiasts, it’s frequently difficult to find even one such film worth seeing in a given year, while elsewhere video gamers have been blessed with a wonderful streak of Resident Evil entries. Zombie fatigue is very real across all visual mediums, and it’s something that has been written about frequently, but the sentiment bears repeating: too many TV shows, too many movies, not many of them good. All the more reason, then, to celebrate the exceptions, and 2016’s Train to Busan, directed by Yeon Sang-ho, was among the most exciting and visceral horror-action spectacles of the year. It didn’t necessarily revolutionize anything; rather, it relied on an elegant handling of story and character, as well as a palpable sense of urgency, that had been missing from other recent forays into zombie fare. It arrived at a time when the Resident Evil series, under the guidance of director Paul W.S. Anderson, was completing its evolution from horror-facing franchise into something altogether more stylized and surfacely artful — a popular pivot among many cinephiles, but also an about-face from the genre tradition of its inception, leaving plenty of viewers less satisfied.

And so, given Train to Busan‘s international success, a sequel was expected. Instead, what came first was an animated prequel of sorts, Seoul Station, also directed by Yeon Sang-ho and released only a month after the original (the director had been previously known exclusively as an animation director prior to Train to Busan). Seoul Station was a far grimmer affair and with few pleasures to be found, as it was too bogged down in the narrative origins of the zombie outbreak that would take over South Korea. Four years later and that sequel has arrived. Peninsula opens with a few sequences that look to re-establish its particular brand of zombie films: one that, while still possessing the requisite genre thrills, chooses to ground itself foremost in the moral quandaries (and resultant thematic and moral weight) that define such an apocalyptic scenario. Notions of camaraderie, piety, treason, and altruism permeate the film, and the plot kicks off Jung-seok, a South Korean marine, who, with his sister and nephew, seeks refuge from the undead scourge aboard a ship. Obviously, everything goes wrong, the ship is quickly overrun with zombies, and Jung-seok watches his family die; he then befriends another lonely outcast, and the pair spend the next few years as outcasts in Hong Kong.

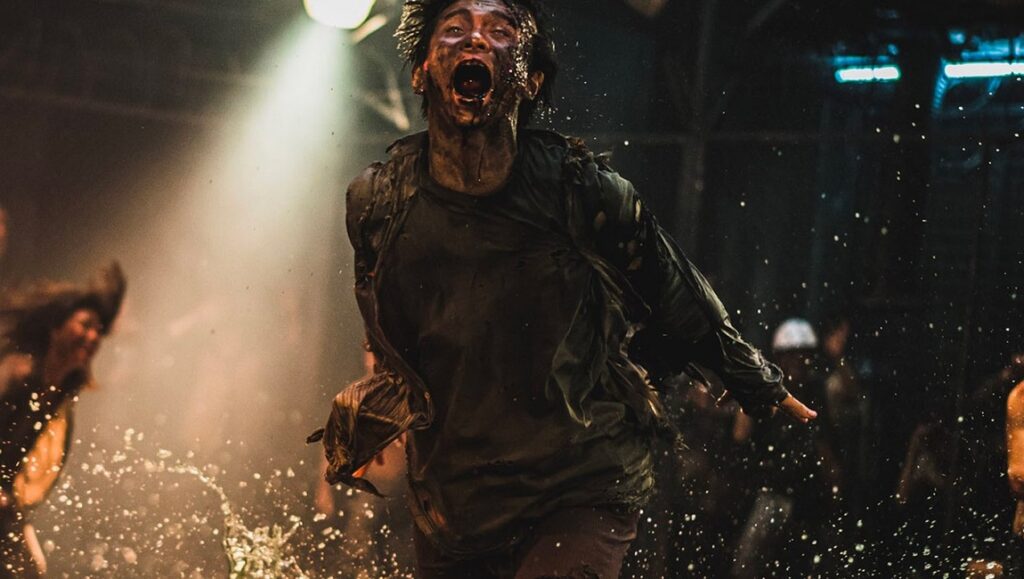

There’s fascinating allegorical potential in the idea of “zombie refugees” in Hong Kong, and it seems as if the film may follow this thread as the local population treats these individuals as if they were infected simply because they speak Korean. Unfortunately, it’s a suggestion that isn’t more than cursorily explored. Instead, Peninsula pivots to include a Chinese mob boss who contacts Jung-seok to form a team that will pillage Incheon, a coastal city which has been quarantined for the past four years. The group soon discovers that zombies “live” in the city, but so does an underground society of sorts that has flourished in the middle of the crumbling streets and buildings. What this means for Peninsula, then, is that it begins to heavily borrow from other post-apocalyptic films — notably the Mad Max series, and particularly Fury Road — and that sense of familiarity dampens much of the film’s potential thrills. The film’s digital imagery further complicates matters: there’s a commitment to compositions shrouded in darkness that, while recalling the particular flavor of Yeon’s animation origins, start to become repetitive across the film’s runtime. Indeed, it remains the human moments — ethical deliberations and acts of heroism — rather than the film’s technical craft or set pieces that evince its most exciting elements, with the exception of a series of car/foot chases that close out the film and inject some stakes into an otherwise commonplace zombie film. If Peninsula doesn’t measure up to its predecessor, it remains a more impressive effort than most other recent depictions in the flagging genre. But in the realm of living dead art, recent video game Resident Evil 3 is superior in storytelling, character, and visual artistry. It’s an unfortunate reality that a medium so essential in the development of zombie craft is falling so far behind other modes when it comes to innovation.

Comments are closed.