Mandibles

Perhaps the most unbefitting title to arrive in the middle of a global pandemic, Quentin Dupieux’s Mandibles defies the current for two reasons. That its titular appendage serves a wholly positive function — of cheerful and robust consumption — rather than reflecting the fearful aversion towards its fluid-spewing, germ-spreading orifice that is virtually ubiquitous today might go over most heads. What does stand out, in contrast with the doom and gloom of Amy Seimetz’s She Dies Tomorrow or the stultifying landscapes of Ben Sharrock’s Limbo (as it were, both are considered unique, though by mere coincidence, to our hopelessly catastrophic climate), is the film’s rollicking disdain for pessimism and constraint. One will be hard-pressed to find anything from this year to top its whimsical chaos and flippant absurdity — traits admittedly suited to the increasingly surreal crises and developments of the world, but which are deployed with an opposite goal in mind.

That goal is success, which in the case of the film’s two dim-witted protagonists, translates to money. Portending untold riches and unending feasts, the prospect of just five hundred dollars spurs best friends Manu and Jean-Gab out of perennial drifting and on to a mission: delivering a mysterious suitcase to a friend’s boss. The contract specifies a car as the mode of transport, so the car-less duo steals a rusty Mercedes which they discover already occupied, by a giant fly in the trunk. Most would balk and run, and only the most ruthless of entrepreneurs would entertain the thought of exploiting the fly for commercial gain; unfortunately, Manu and Jean-Gab fit neither description. They choose the latter option anyway, deferring the inevitable question of profit to concentrate on more immediate concerns — food, lodging, a training regimen for newly christened “Dominique,” and setting fire to their newfound home.

Comic irreverence, a staple of Dupieux’s, works best unrestrained; Mandibles forgoes the rational subtexts of lesser comedies and shoots for what Peter Farrelly’s Dumb and Dumber, also unrestrained but with an unwanted addition of the borderline psychotic, missed. It has its own staples: mistaken identities, unlikely coincidences, dead pets, arguably offensive characterizations (Adèle Exarchopoulos; not a lesbian). But it is another thing altogether to springboard from one to another with the impulsive exuberance reserved for clowns. It’s something Mandibles pulls off tremendously well in an economical 77 minutes — the fly barely flies, and yet the viewer’s jaw already aches from sagging too long at the seeming impossibility of witnessing both the audaciously moronic and masterful. Morris Yang

The Doorman

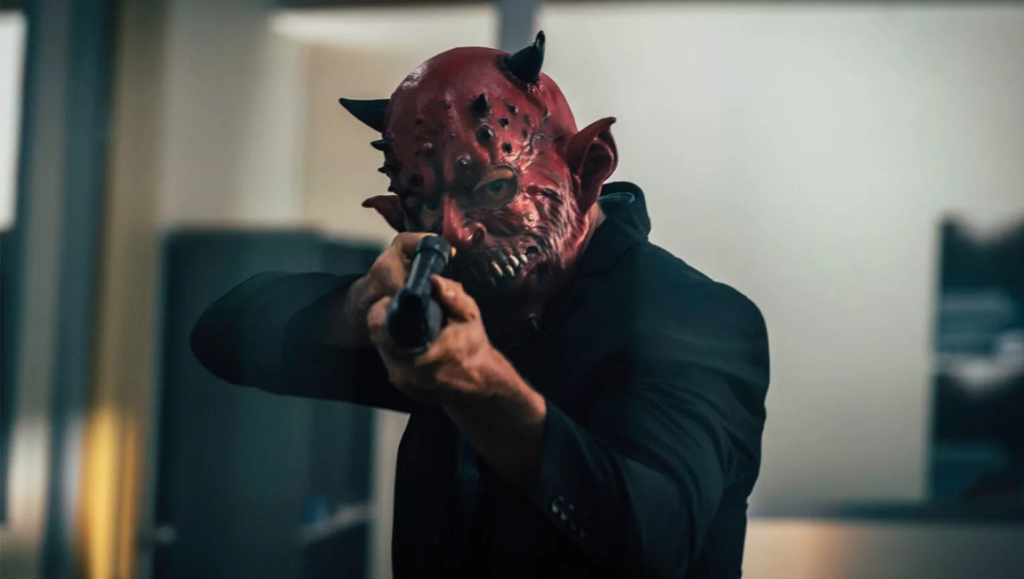

With direct-to-video/streaming action films now a bonafide cottage industry with their own tropes, star filmmakers and performers, and aesthetic trappings, the real mediocrities are becoming more and more prominent and are seemingly attracting a classier pedigree of talent. Hence, The Doorman. It stars Australian model Ruby Rose — late of the Batgirl TV series and featured prominently in the final Resident Evil and memorably in John Wick Chapter 2 — and is helmed by former Japanese Extreme bad boy Ryûhei Kitamura (who helped kickstart that boom with his novel but not-very-good DIY debut Versus).

Rose plays Ali, a former Marine now retired after a mission-gone-wrong, who settles in New York with a job, uh-huh, working the door at a ritzy apartment building where she’s surprised to discover that her late sister’s widower and their kids are tenants. She also befriends an elderly couple that is essential to the plot, which kicks off when her boss turns out to be in cahoots with a bunch of thieves — lead by Jean Reno, really slumming it here — who take over the building in search of some stolen art. Honestly, there’s not even an attempt to disguise the Die Hard knockoff aspirations here, which would be fine if the action were in any way inventive or exciting. Kitamura has sacrificed much of his typical exuberance behind the camera in favor of a lot of generic coverage and janky edits that conceal most of the best action beats, and the hand-to-hand fighting is never much more than merely competent — that sense of lethargy informs the entire film, leaving little to outright praise or decry. Rose acquits herself just fine, doing the usual steely-but-vulnerable thing you’d expect from this material, but The Doorman is just far too bland an endeavor on which to waste her talents. Matt Lynch

It Cuts Deep

There is a kernel of a good idea buried somewhere within the shitstorm that is the new horror-comedy It Cuts Deep. Unfortunately, writer-director Nicholas Santos, making his feature-film debut, has no idea how to extract it, resulting in an insulting and reductive film that paints men as commitment-phobe monsters and women as marriage-starved shrews. Sam (Charles Gould) and Ashley (Quinn Jackson) are a couple cut from the sitcom cloth: he is an overweight, bearded lay-about; she is thin, attractive, and likes to go on morning jogs. She desperately hopes he pops the question on their Christmas trip to his parent’s house, while he just wants to try “butt-stuff.” (Just to be very clear about the kind of film that It Cuts Deep is, “butt-stuff” is said roughly a dozen times within the film’s first 15 minutes.) They drink wine and eat some of the most unappealing food to ever feature onscreen. And once in a while, just to remind that this is indeed a horror film, a loud chord of music lights up the soundtrack. Oh, and the film opens with a brutal murder at the hands of what appears to be Michael Myers from the waist down, and Santos flashes back to this image whenever the film is in need of a jolt. Next, Sam’s childhood friend Nolan shows up — he is played by John Anderson, who performs as if retroactively auditioning for the titular role in The Cable Guy. Sam is threatened by him even though he is a bonafide whackjob, and his reasons for hating Nolan are never properly explained. Meanwhile, Ashley keeps forgiving his disgusting transgressions because no one in this film reacts like an actual human being. It’s almost impressive how a film that runs only 77 minutes can be so unfocused and constructed of such filler, especially when its true purpose is finally revealed: the threat of commitment and a family can drive some men insane — literally. Setting aside the absolutely abhorrent gender politics, It Cuts Deep doesn’t even have anything new to contribute to the regressive subject matter, thinking that a few bits of gore will somehow distract the viewer from its utter emptiness. The horror aspects are never scary, the comedic bits fail to inspire even a single laugh, the acting is inconsistent across the board, and the directing is tolerable at best. It cuts deep? This doesn’t even leave a mark. Steven Warner

Bloody Hell

As film festivals have gone largely virtual in the face of our new pandemic reality, many critics have lamented the now-absent communal aspect of these events; gone are the post-screening conversations and interviews, the mingling in long lines, and the thrill of watching a movie wash over a rapt audience. Particularly hard hit are “midnight madness” style screenings; horror, like comedy, frequently works better with a crowd. One imagines watching Bloody Hell with such a crowd, settled in late at night after a long day of more reputable fare, probably a few drinks deep, ready to cut loose and get rowdy. Alas, any energy that might have infused Bloody Hell with an extra-textual quality is lost when viewed at home, alone, and the film’s issues become more difficult to paper over. Directed by Alister Grierson and written by Robert Benjamin, Bloody Hell is a horror-comedy that forgets to be scary and gets bogged down by an obnoxious sense of humor. Ben O’Toole stars as Rex, an improbable blend of Ash from the iconic Evil Dead films and Mac from Its Always Sunny in Philadelphia. After a whiplash-inducing prologue, where he thwarts a bank robbery and gets sent to prison for his efforts, Rex gets released only to find that he’s become a social media star. Deciding he needs a vacation, and hoping to avoid his adoring public, Rex hops a plane to Finland. As luck would have it, he’s immediately kidnapped and strung up in the basement by what appears to be the Finnish version of the Texas Chainsaw Massacre clan.

Grierson and Benjamin (who also edited the film) burn through plot at a ludicrous pace, keeping things lively with ostentatious fast cutting and lots of flashy camera moves. Once Rex is relegated to the basement holding pen, the film’s biggest misstep is thrown into sharp relief. Here, the filmmakers have literalized Rex’s interior monologue, personified on screen as a second Rex that only he can see. This move casts O’Toole in a dual role that mostly requires he talk to himself, although the film makes clear that no one else can see this psychic projection. Less clear is whether or not Rex is supposed to be schizophrenic, as his visualized id becomes pushier and more caustic. Whatever the case, the gimmick wears thin quickly, particularly once we meet Alia (Meg Fraser), the one family member who doesn’t enjoy the practice of kidnapping and murdering tourists for food. At this point, the film sort of turns into a weird rom-com; it pumps the brakes on mocking Rex’s alpha male shtick and instead begins indulging it. Throw in some Family Guy-style cutaway gags and Bloody Hell starts getting stale, fast. Still, this is a strong cast and there’s a sharp sense of humor buried somewhere under all of the faux-ironic posturing and annoyingly flashy style. O’Toole is at least a legitimate find, and Grierson and Benjamin certainly have talent; if they can get some of these belabored tics out of their system, they could actually make something pretty special. Fingers crossed. Daniel Gorman

Hunted

Vincent Paronnaud’s new horror-thriller Hunted opens with a campfire tale brought to life using a gorgeous animation style that combines black, blocky cut-outs and a background of ethereal gold. The message is bluntly stated: “The company of wolves is better than that of man.” Paronnaud then spends the remaining 86 minutes proving that point, but unfortunately forgets to add anything in the way of depth or insight, leaving the viewer to wonder what is to be gained from enduring his rather heinous take on Little Red Riding Hood. A businesswoman in a bright red coat, Eve (Lucie Debay), ends up drunkenly going home with the wrong man (Arieh Worthalter), and is forced to fight for her life in the woods after escaping his clutches. What follows is a monotonous foot chase in which Eve endures repeated close calls with her big bad wolf, but always escapes just in the nick of time. This ultimately leads to a showdown in a suburban model home that could be a commentary on deforestation and urban sprawl, but honestly, who knows.

As the co-director of both Persepolis and Chicken with Plums, it seems fair to at least expect Paronnaud to deliver visually, but aside from that aforementioned opening and a moment involving a car, a kiss, and a wild boar — it’s as bonkers as it sounds — memorable imagery is sparse. Even as a tale of female empowerment, Hunted fails miserably, as Paronnaud is far more interested in spending time with his big baddie than the woman at its center, who is instead reduced to a series of grunts and wails. The film also keeps hinting that the woods will ultimately fight back in the young woman’s defense, Long Weekend-style, but aside from a couple of camping survivalists and an angry bird, nothing ever comes of it. There’s really only one expectation that Paronnaud successfully upends: he constructs his film in the familiar horror shape of a rape-revenge tale even as rape doesn’t feature, which is both a welcome bit of restraint and a nifty genre modification, but it simply isn’t enough — and no, a paintball game that suddenly turns Eve into a warpaint-clad William Wallace will not suffice. Perhaps more would be forgiven if Paronnaud had delivered on the terror front, but aside from a few moments of body horror, there isn’t much here to sustain the average genre fan. Hunted is watchable, but not much else. The victim at the heart of its story deserves to be treated as more than a lazy prop. Steven Warner

Comments are closed.