Billie offers a look at one complex woman through the lens of another, each with a distinct story that director James Erskine manages to weave into an impressive if unambitious narrative.

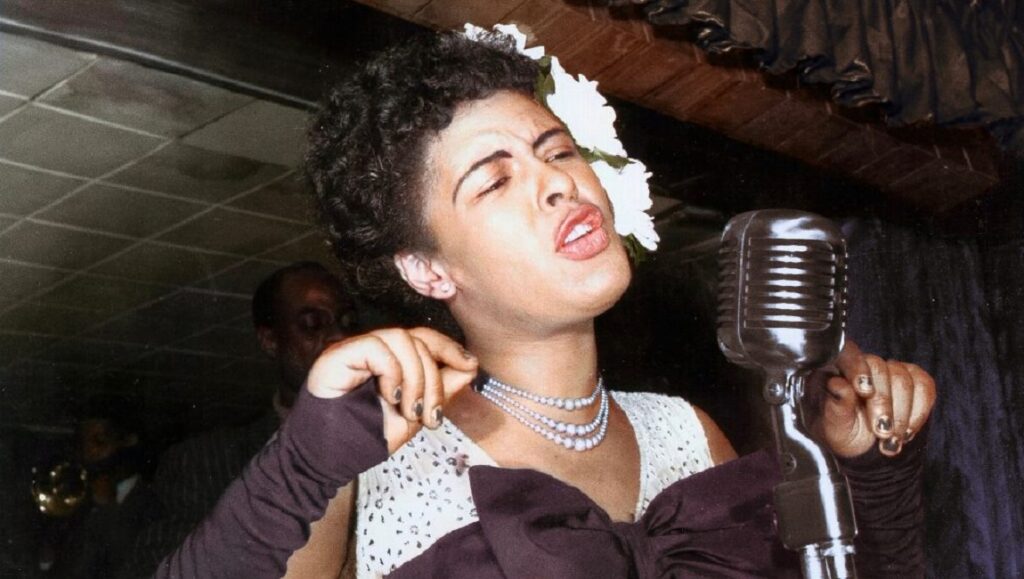

In February 1978, young arts writer and journalist Linda Lipnack Kuehl was found dead under mysterious circumstances, thrown out of a window in Washington, D.C. For roughly a decade, Kuehl had dedicated herself to uncovering the true story of the legendary jazz artist, Billie Holiday. Despite recording hundreds of hours of interviews with many of Holiday’s collaborators and friends, the 38-year-old biographer never found the opportunity to publish her book, and the content of her tapes was left unheard. Fortunately, Kuehl’s decade-long research and immense audio archive can finally see the light of day, as it provides the considerable groundwork for British filmmaker James Erskine’s Billie. Indeed, this genesis sets Erskine’s biography apart from most other portrait-docs as it primarily relies on these recorded interviews rather than the typical talking-head interviews audiences have been conditioned to expect from the format — an on-camera conversation with Linda’s sister, Myra Luftman, proves the only exception here. It’s not only a novel approach but a strategically sound one, as Billie is not only a documentation of one of the greatest voices in the history of music, but also a platform for Erskine to evoke unheard voices from the past, affording them space to narrate their own history as the director carefully compliments and enhances through stock footage and archival images. A similarly successful example of Erskine’s delicate method can be seen in how he connects different crucial incidents of Holiday’s life with songs from her discography; as Holiday states in an interview, “The things that I sing have to have something to do with me and my life.” “God Bless the Child” accompanies details of her birth in Baltimore, “Saddest Tale” plays alongside talk of her work as a prostitute in her teenage years, and the singer’s famous and famously controversial “Strange Fruit” plays after Erskine recounts Holiday’s split with her all-white Artie Shaw band.

Indeed, in Billie, Erskine is very consciously up to something more complex than the usual; he doesn’t intend to merely recount the fabled difficulties of Holiday’s life, including destructive romances, her path from smoking “reefer” to struggling with cocaine and heroin addiction, and the subsequent and harassing narcotics investigations. For the director, what is far more fascinating are the ways an icon like Holiday can maintain relevance, even still featuring in present discourse, after over half of a century. Erskine guides his film toward issues of racial bigotry, sexual domination, and discrimination, underscoring (although with admitted imbalance) how the tragic fates of Holiday and Kuehl, two women from wholly different backgrounds, so profoundly resonate in each other’s story. Even if Billie retains a linear and relatively conventional structure, and probably isn’t as ambitious as it could be, one might still qualify its efforts as strangely fruitful thanks to Erskine’s audacious confrontation of the material. Indeed, the vision feels quite in tune with a sentiment conveyed partway through the film: “It was Billie’s interpretation […] not the song itself.”

Published as part of Before We Vanish | December 2020 — Part 2.

Comments are closed.