When I was 22, my best friend and I lived together for a while in the apartment where I grew up. We were a twenty-minute walk from the subway’s last stop, in a neighborhood that was years away from any semblance of trendiness. My mom was traveling for months at a time, and in her absence, Rose and I did the usual things that recent college grads do: applied to jobs, drank cheap wine, went on bad dates. It was unsustainable, of course: my mom came back, Rose went back to the west coast, and I got a “real” job and moved out. Our stint as roommates was never meant to last forever, but while it endured, it was formative and precious and perfect.

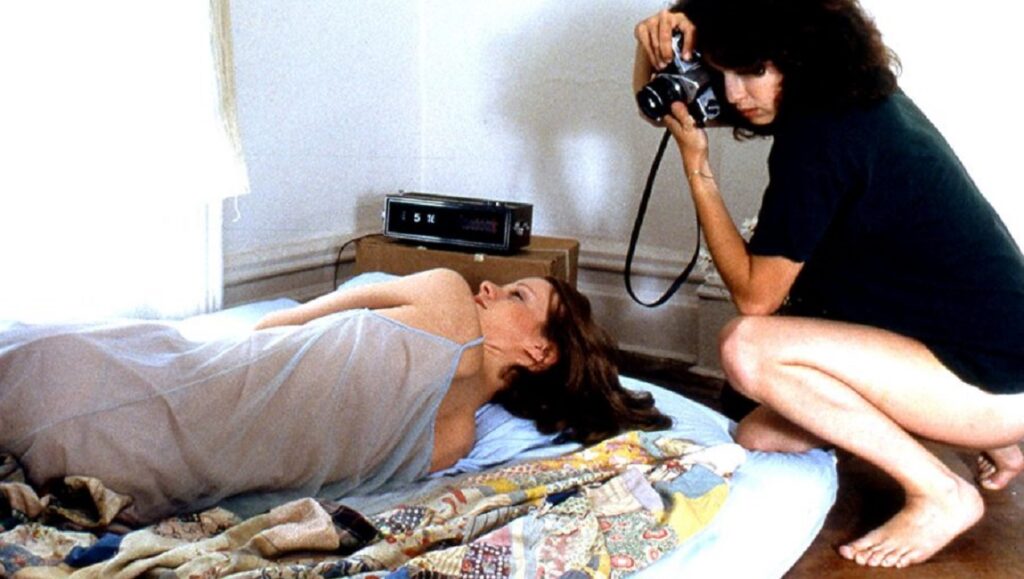

Almost everything about Girlfriends, Claudia Weill’s 1978 debut feature, reminds me of that time. Girlfriends isn’t a schmaltzy rom-com — its romantic relationships are a little too realistic — or a standard coming-of-age narrative — its characters are well into their mid-20s — even though it stars two women and takes place in New York City. Instead, it’s a gently evolving snapshot of wild-haired Susan (Melanie Mayron), a photographer, and her best friend Anne (Anita Skinner), an aspiring writer, whose lives take divergent paths when Anne gets married and moves out of their shared apartment. With wit and compassion, Weill explores the conflicting, confusing, and downright embarrassing emotions that her characters experience as they navigate this life change. The film excels in capturing the unique, universal angst of not wanting to be alone, but not being ready to let someone in. It’s not quite depression, but it’s not altogether far off either.

Weill’s background in documentary filmmaking imbues Girlfriends with that same unvarnished sensibility. Apartments are suitably grimy, banter refreshingly stilted. Anne breaks the news of her marriage in the laundromat. “How can you be sure when you’re so unsure?“ Susan asks her, stunned. “I don’t know, but I am,” she replies. Without the steadying presence of a friend and roommate, Susan finds herself adrift. She struggles to get her career off the ground; the few photos she manages to sell are cropped without her permission. It’s only when she bluffs her way into a meeting that her prospects improve. To supplement her income, she takes snapshots of weddings and bar mitzvahs, fostering a quasi-romantic relationship with the much-older Rabbi Gold (Eli Wallach). Anne, meanwhile, moves from the city to the suburbs with her pedantic husband Martin (Bob Balaban) and quickly starts a family, her writing time increasingly encroached upon by domestic concerns. For her part, Susan’s concerns throughout the film are more self-centered, but no less existential. Is her art good enough? Is she good enough?

Tempting as it is to write off Girlfriends as another entry in the “gals in the big city” genre — with Lena Dunham’s Girls and Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha as obvious 21st-century incarnations — Weill and screenwriter Vicki Polon choose the far more interesting path of lingering on false starts and not-quites. Susan and Rabbi Gold’s first date is canceled before it begins, the weight of his domestic responsibilities too heavy for either of them to spirit away. Her relationship with Eric (Christopher Guest), whom she met at a party, seems to sputter to a standstill when she refuses to move in with him — not because she doesn’t like him, but because she can’t bear to give up her apartment, and, by extension, her independence. She misses an important meeting the night before her gallery opening and is told, only half-mockingly, that she needs to grow up because she is now a professional.

As Susan and Anne drift apart, we see how the shadow of their friendship seeps into their romantic relationships. They love and miss each other, but absence has curdled affection to mutual resentment: Susan, at being left behind, and Anne, at being misunderstood. Crucial to the film’s unassuming genius is the way these women traverse this gulf and reunite. Having skipped Susan’s gallery opening, Anne reveals that she had an abortion without telling her husband because she “didn’t want to be talked out of it.” This knowledge is all the more shattering in the context of the rest of the film: the way Susan catapults herself away from a creepy cab driver, the casual misogyny of the editor who cropped her photo. So as Martin’s car pulls up to the house, the two women exchange a glance that contains the entire universe of their friendship: resilient, evolving, always growing.

Part of Kicking the Canon – The Film Canon.

Comments are closed.