Both politically and aesthetically, New Order is an ironic and troubling proclamation of solidarity with the old, regressive guard.

The refinement of taste, an ongoing exploration of one’s personal experience, while all well and good, always runs the risk of becoming solipsistic, of neglecting the areas of exploration that fall outside of one’s interests. This is at least one way of justifying an encounter with the Cannes-anointed output of Michel Franco, whose warm reception on the festival circuit has, over the years, become something more like a red flag. His latest, New Order, which arrives hot off its Grand Prix win at the Venice Film Festival, seems about as good a place to start as any other. Though having now seen the film, I should add: as good a place to end, as well.

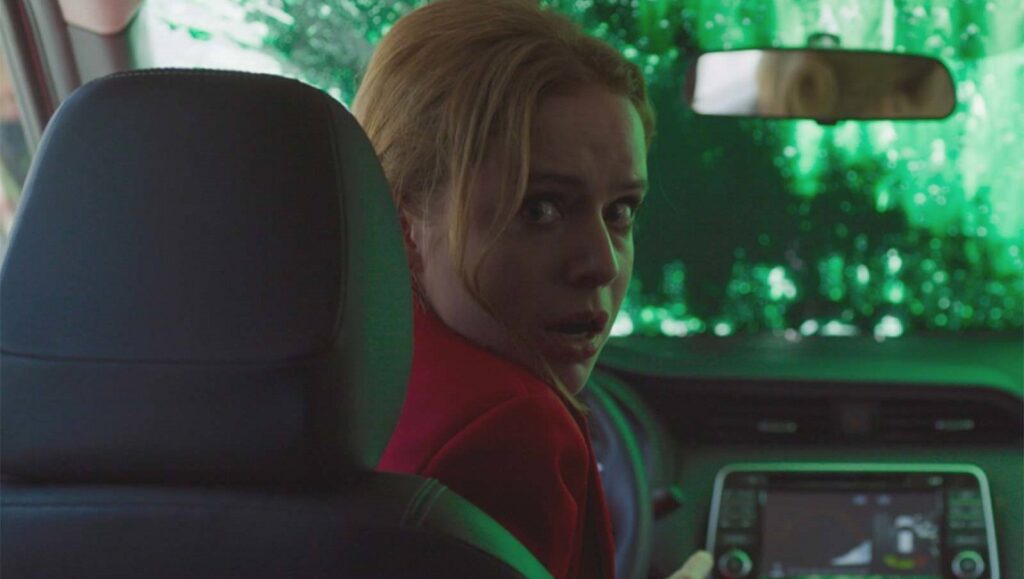

What immediately stands out in New Order — especially to a viewer whose only previous exposure to Franco’s work is the hilariously glib ending of Chronic — is not the director’s retrograde politics, which equates working-class revolution with the machinations of the neoliberal police state; or his hackneyed dramatic instincts, which pile one hot-button topic upon another (health care, class resentment, surveillance, to name only a few); but rather, his unimpeachably competent art-house stylings. For better or worse, the man can serviceably direct chaos. And New Order — which follows a wealthy, sealed-off family, who have gathered for a wedding as a populist uprising brews outside of their door, eventually spilling over — offers myriad examples of this dubious mastery. A crane shot fluidly follows the patterns of elegantly arranged corpses; sudden, loud gunshots disrupt distended periods of bourgeois bliss; and panoramas of ominous, vacant urban spaces suggest the pangs of a populace under siege. In all such moments, Franco seizes upon the one thing the liberal commentariat never fails to see as profound: ambiguity, that one-size-fits-all sentiment, capable of stoking the sympathies of the Blue Lives Matter crowd even as it solicits pathos for the dispossessed. That Franco clearly sees his title as ironic tells us everything we need to know about what side he’s actually on. In politics, aesthetics, and the intersection between them, New Order stands with the old guard.

Originally published as part of TIFF 2020 — Dispatch 2.

Comments are closed.