In Hong Kong’s tropical humidity, where sweltering bodies cram around mahjong tables or hunch over noodle stands, how can two people in a forbidden romance possibly cope? For Shanghainese émigrés and next-door neighbors Chow Mo-wan (Tony Leung, in a role that won him Best Actor at Cannes) and Su Li-zhen (an exquisite Maggie Cheung), the answer is simply to endure. Released in 2000 and set throughout the 1960s, Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love is an opulent, highly evocative melodrama of romance and repression. Chow, a journalist, has a penchant for kung fu novels and a wife who pretends to work late. Su, an assistant at a shipping company, is often left alone while her husband is away on business. They suspect their spouses are conducting affairs, only to realize they are — with each other. Following this revelation, their interactions blossom into a friendship that soon evolves into something deeper, but a combination of moral compunction and social expectation prevents them from ever acting on their desires. They may act like lovers, going so far as to regularly rent a hotel room, but once there, all they do is listen to records and write kung fu novels. As years pass, Chow leaves Hong Kong for Singapore and then Cambodia, each trip punctuated by a near-miss or aborted reunion.

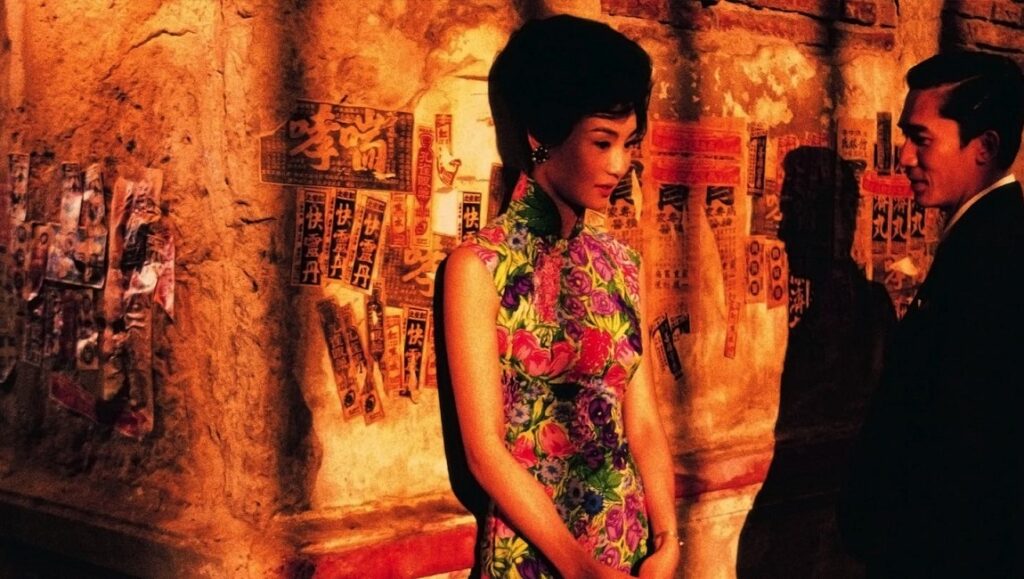

Outside of their snatched hours together, Su and Chow are engulfed in an all-consuming and inescapable solitude. She fills her nights with solo trips to the cinema and outings to the noodle stand, not bothering to change out of her pristine cheongsam dresses. There is no remedy for the intensity of their loneliness, not even a love affair; the only way out is through. Almost every aspect of the film highlights this principle, from the recurring strains of the valse triste that represents their futile longing — they are literally dancing around each other — to the slow-motion cinematography that stretches and warps their moments apart. The time they happen to share around the apartment block is spent in dimly-lit halls or narrow doorways, in which they are forced into physical proximity while struggling to maintain an emotional distance. This superficial intimacy offers respite but not redemption: neither wants to be the one to initiate an affair, just as neither can believe that their spouse made the first move.

With its impenetrable social structures, highly choreographed movements, and carefully couched declarations, In the Mood for Love is as much Victorian novel as classic art house cinema, down to the secondary cast of busybody neighbors. Personal happiness doesn’t seem to matter and dialogue is dense with layers. Consider the scene when Su confronts Chow about having an affair: it’s only halfway through the conversation that we realize he’s standing in as her husband, and they’re merely acting out a confrontation in preparation for the real thing. Read differently, they are also role-playing a different marriage — theirs. If they’re cheating on each other, that must mean they’re together. Only in such moments can they pretend to be a married couple having a typical married-couple argument. Similarly, since decorum prevents them from sharing a meal at the local noodle stand, they take cabs to a Western-style restaurant for dinner. In order to escape their domestic constraints, they must shed not only their neighborhood, but their entire culture.

It’s appropriate that a film so concerned with atmosphere is absolutely stunning in its production design and costuming. Both aspects were handled by William Chang, who also edited, leading to a sumptuous, deeply cohesive visual language that relies heavily on color, texture, and the interplay of light and shadow. Maggie Cheung’s wardrobe of 25 or so cheongsams (also known as qipaos) is rightfully celebrated as one of the most memorable aspects of the entire film. These deeply saturated, form-fitting dresses, with their sensuous silhouettes and high collars, are the perfect way to convey the film’s historically accurate aesthetic of reserved but undeniable femininity. They also limited Cheung’s freedom of movement, lending her already measured gestures a slight stiffness that further embodies the restrictive social mores of the era. Spectacular as they are, Su doesn’t have an endless supply but re-wears several throughout the film, in keeping with her more modest socio-economic class. This applies to the rest of the production design, down to the apartments’ colorful but faded wallpaper and slightly shabby furniture.

It’s equally fitting that Su and Chow learn of their partners’ affair through their clothes. Chow’s wife carries a handbag just like Su’s, purchased by her husband on a business trip. Both men have the same tie, bought by Chow’s wife. Their affair is deduced through a subtly shared wardrobe instead of anything as trite as overheard conversations or caught-in-the-act bedroom scenes. Finally, it’s worth noting that Su also shops for her boss’s mistress, at one point buying her a scarf with green checked wrapping paper that mirrors one of her own dresses. She’s already complicit in one affair and unwilling to cross the final moral boundary of instigating another.

As the film jumps forward in time, with Chow traveling to Singapore and then Cambodia, their uncomfortable physical proximity is replaced by excruciating near misses. She is too late to meet him at their hotel room, and only the red curtains in the hallway have witnessed his departure. In Singapore, she calls him but never speaks, leaving a lipstick-stained cigarette butt to signal her presence. When Chow visits their old apartment building, the new landlady tells him that everyone has left — except for a woman next door who lives there with a young child. He doesn’t stay long enough to discover that it’s Su. Wong deploys another lingering shot of an empty hallway to let this sink in, though by then Chow has already left for Cambodia.

Amidst the monumental ruins of Angkor Wat, he leans against a crumbling wall and whispers something into a hole before covering it with dirt. This is how you get rid of a secret, he had told his friend Ping. A mournful cello score recalls the violins of the valse triste, but the luxury of slow motion, like the languorous romantic possibility that marked the film’s earlier years, is long gone. He is alone except for an anonymous monk who observes him from a dispassionate distance, a reversal of the nosy neighbors who plagued their time in Hong Kong. The doorways of their old apartments are replaced by timeless temple gates, but their holiness is no less restrictive. Loneliness and regret follow no matter how big the sky, how old the stone. They can go anywhere in the world except back in time.

Part of Kicking the Canon – The Film Canon.

Comments are closed.