Haruhara San’s Recorder

The winner of FIDMarseille International Competition, as well as the recipient of its Best Actress award in that category, Haruhara San’s Recorder proves an appropriate choice for the festival’s (basically) top prize, speaking to this year’s apparent curatorial themes and adhering to a pace not dissimilar to that of jury president Lav Diaz. The fourth feature from Japanese director Kyoshi Sugita, whose work has yet to gain traction or distribution in North America, Haruhara San’s Recorder tracks as the work of a filmmaker with a developed sensibility of their own, a mix of rigorous, mostly stationary camerawork with an unpunctuated structure, scenes flowing in and out of one another without ever pausing for exposition or context.

This choice in narrative stylization is at least in part inspired by the nature of the source material Sugita has adapted for this film (his previous features do appear to be constructed similarly), a tanka of the same title. Poems of this traditionally Japanese genre (when not translated/Romanized) are written out as a single uninterrupted line of 31 syllables, something Haruhara San’s Recorder is consciously trying to approximate through the gentle flow of its screenplay and the unassuming nature of each cut. Setting the tone and rhythm of what’s to come, the film introduces Chika Araki as a young woman moving into a new apartment, Haruhara San’s Recorder picking up right as she is receiving the keys from the previous tenant who has no interest in leaving a forwarding address or being contacted following this transaction. Peculiar, but never threatening necessarily, Sugita’s script leaves that and many other such moments to hang, implying conflict and development that won’t manifest, never quite providing us with enough information to make out a sensible continuity without shifting over into the surreal or fantastical. Shot digitally in very bright, 1:33 compositions, Haruhara San’s Recorder does bear some resemblance to home video footage, which combined with the refusal of conventional plotting, often colors the proceedings as candid; moments that we are quietly allowed to peek in on. We catch glimpses of screwball-esque domestic dispute, brief jaunts to the café, instances of performance and painting and filming (while the film’s title most immediately refers to the instrument, Sugita inevitably has some fun with double meanings); the only signal that time is passing being Araki’s eventual change of hair color. Its possible none of these scenes would be particularly cinematic were they played out in full, but Sugita has culled the poetic from day-to-day life (again, a theme that populates much of the FIDMarseille lineup this year), stitching them back into something that escapes mundane logic for something more emotional and lyrical. A curious film deserving of this jury’s praises, Haruhara San’s Recorder stands out as an intelligent reimagining of cinematic storytelling, one with a radical idea of how to move past the usual rigidity of narrative and out into something more fluid and evocative.

Writer: M.G. Mailloux

The Invisible Mountain

A continuation of the Trypps cinematic approach he’s established, but merged with material adapted from René Daumal’s surrealist fantasy novel Mount Analogue, Ben Russell’s latest, The Invisible Mountain, is challenging to define outside the terms set by the experimental director over the last two decades of his career. A documentary by the director’s own account, The Invisible Mountain is largely comprised of concert footage and candid discussion between cast and crew (one and the same, really) that would qualify as nonfiction, but informed and structured around the plot of Daumal’s unfinished 1959 text. In part an inspiration for Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Holy Mountain, Mount Analogue’s story of an expedition team setting out to climb a mountain on an invisible continent doesn’t make immediate sense as the inspiration for a documentary, but Russell takes a surprising and effective approach to adaptation not dissimilar to that of Straub/Huillet, using the actual words of the source material to bring the author’s world into ours.

Like the aforementioned Trypps films, The Invisible Mountain is something in between landscape and psychedelia, the quest depicted in Mount Analogue paralleled here by an extensive hike across North Eastern Europe that takes Russell and his primary subject, Tuomo Touvinen, from Finland down through Belarus. Shadowed by a Sonic Youth-sounding noise band whose live performances punctuate the long, durational stretches of walking footage, Russell captures this footage himself, serving as his own camera operator (he subscribes to the Rouchian idea of ciné-trance), and so the journey of his protagonist becomes both literally and metaphorically his own. Aware of this dynamic, The Invisible Mountain ultimately moves toward conflict between artist and subject, bringing Russell on screen to stoke doubts about the sustainability of the project, raising questions about its authorship and invoking the untimely passing of Daumal as an ill omen. It’s here that Russell once more complicates our understanding of his film, blowing away the distinction between fiction and reality so it becomes challenging to determine where dramatization begins and ends. The Invisible Mountain poses an idiosyncratic vision for literary adaptation that estimates the original poetically while demonstrating its contemporary relevance. Brought to life with an avant-garde sound design and green screen reappropriation, the world that Russell conjures here is appealing in its accessibility, organic yet totally, convincingly fantastical.

Writer: M.G. Mailloux

Saturn and Beyond

Irish filmmaker Declan Clarke, who specializes in a political cinema focused on the great socialist philosophers of Europe’s last couple centuries (Engels and Luxemburg, for instance), has (unsurprisingly) yet to find much attention in the U.S. film scene, nor at the bigger international festivals. Working in narrative and nonfiction modes, and interweaving elements of noir and espionage fiction throughout both (many of his films including an “Agent” character played by the director), Clarke’s vision is surely an intriguing one, though the sort that’s rarely celebrated outside festivals of a certain size and scope.

Perhaps that could shift for Clarke with his latest nonfiction piece, Saturn and Beyond, which had its world premiere at FIDMarseille and was ultimately awarded the Georges De Beauregard International Prize. A partially autobiographical essay film, Saturn and Beyond’s big universal themes (that also happen to literally concern the universe) and relatable existential ruminations put Clarke in proximity of his broadest audience yet, though this shouldn’t be taken as suggestive of an unchallenging experience. Intertwining a brief summary of the development of electronic communication technologies (i.e., telegraphs, phones) with an overview of the Cassini-Huygens Saturn research mission and personal anecdote concerning the director’s father’s post-Alzheimer’s decline and eventual death. Linking these three tangents (kind of) are Clarke’s remembrances of his father’s establishment of the now-defunct Irish Museum of Broadcasting, a shuttered space that Saturn and Beyond brings the filmmaker back to, capturing its abandoned archive of communication ephemera in substantial 35mm photography. Otherwise mostly shot on 16mm (the director’s film medium of choice) and largely told in silence through title cards (reminiscent of a similar device employed by Su Friedrich in I Cannot Tell You How I Feel), Saturn and Beyond attempts to navigate between blunt fatalism and existential wonder, addressing the inevitability of universal decay directly while reaching at meaning never quite grasped within the 60-minute runtime. Honestly expressed and certainly ambitious, Saturn and Beyond does a nice job of holding space for Clarke’s raw emotional display, inviting the audience to participate in a mutually meditative experience. Yet, Saturn and Beyond is also overwhelmed by the combined unwieldiness of the leaps made in its script and the grimness of Clarke’s more emotionally confrontational moments. More effective in its immediate expression of grief than as the cohesive essay it set out to be perhaps, it’s still a document of something impressive, albeit rendered messily.

Writer: M.G. Mailloux

Taxidermize Me

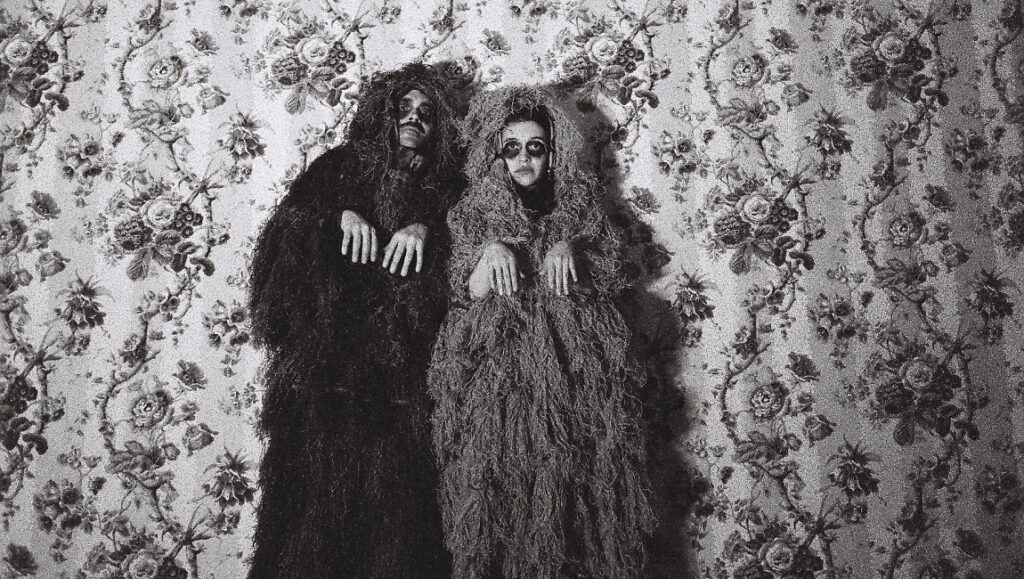

Most widely known for directing The Ballad of Genesis and Lady Jaye, the nonfiction chronicle of Throbbing Gristle founder Genesis P-Orridge’s body mod-heavy Pandrogyny project, the bulk of Marie Losier’s filmography tends to inhabit more esoteric formal territories. For almost two decades now, Losier has specialized in a particular type of experimental narrative short fiction, whimsical and reverent of the cinematic, her work brings to mind that of the Kuchar Brothers and Guy Maddin, with much of her work spent dreaming up avant-garde portraiture of these very same artists (Tony Conrad and Alan Vega have also received this treatment), placing them in front of the camera in surrealist scenarios emblematic of their spirit. Her latest short, Taxidermize Me, does the same, but for the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, Paris’s hunting and nature museum, who commissioned Losier to film this in their space while it was closed off to the public earlier in the pandemic. The museum’s collection of taxidermied wildlife provides Losier with a colorful and expressive “cast” to work with, commemorated in zippy 16mm cinematography, contrasted with a collection of human actors in heavy makeup and ghillie suits. A loose narrative emerges as a hunter pursues the museum-bound humans, his gunshots rendering them into taxidermied creatures. The metaphor here isn’t so hard to decipher, but Losier’s nimble pacing (10-minute runtime) and general sense of playfulness keep Taxidermize Me away from anything patronizing, achieving instead a more unique tone resting somewhere between manic and meditative.

Writer: M.G. Mailloux

Comments are closed.