Prisoners of the Ghostland is neither Sono nor Cage’s finest work, but it’s a good enough fix for those in need of either’s madman energy.

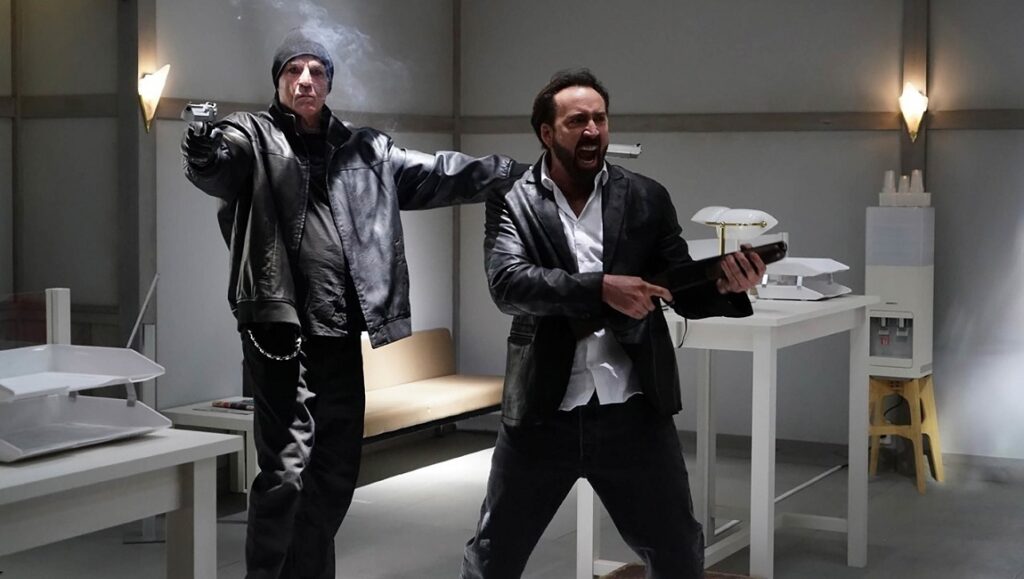

If there’s any director working today that understands what Nicolas Cage means when he describes his style as “nouveau shamanic,” it’s Sion Sono. Cage and Sono work through similar means, a highly-stylized and often wildly over-the-top expressivity, getting at the emotional truths that make their work so compelling. After all, Sono’s masterpiece, Love Exposure, is at its core a melodrama, albeit one replete with severed dicks, Female Prisoner Scorpion cosplay, and up-skirt photography performed like ninjutsu. Sono’s actors routinely perform like Cage, going well beyond the range of actorly realism to arrive at something more affecting and memorable. Prisoners of the Ghostland, the collaboration that had to happen, is sometimes lacking in the emotional rawness that characterizes each man’s best work, but it largely makes up for it with imaginative production design, memorable action spectacle, and gorgeous cinematography.

Originally conceived to shoot in America, Ghostland was delayed when Sono suffered a heart attack and, to save the film, production moved to Japan. To that end, the film’s style is that of East meets West writ large, with much of the film taking place in Samurai Town, an old western-styled town that sports as many cowboys, including Bill Moseley’s Governor, as it does samurai. The set for Samurai Town most clearly recalls Tokyo Tribe’s fantastical locations, and, like that film, most of what’s depicted on screen would seem more at home in an anime, where expressivity is valued over grounded verisimilitude. Sono casts Cage not as the tiresome meme, but as a symbol of American masculinity. If the mission that the Governor gives Cage’s hero sounds an awful lot like Escape from New York, well, Cage is Sono’s Kurt Russell, as well as a part of John Wayne’s macho lineage. Our hero must go to a place called the Ghostland to rescue the Governor’s granddaughter (Sofia Boutella, who doesn’t have a lot to do) from the clutches of radioactive mutant ghosts. Any false move and the suit Cage has been zipped into will trigger highly localized explosions. Act with violence towards a woman? Lose an arm. Feel even a little bit horny? Bust a nut.

When he arrives at Ghostland, Cage finds a city made of wooden platforms in the shadow of a nuclear power plant where time stands still. Some people here have been turned into mannequins — again, a detail here with a clear counterpart in Tokyo Tribe — and the look of them, and many of the village’s other eccentrics, is both unnerving and delightfully novel. Sure, this town beset by radioactive monsters clearly recalls The Road Warrior, but the feeling of the Ghostland is a distinctly Sono pop confection. Yet again, the director finds himself contending with the momentous event of his latter-day career: the 2011 earthquakes and subsequent nuclear disaster at Fukushima Daiichi. Films like Himizu, Tokyo Tribe, Love & Peace, and The Whispering Star are all preoccupied with the fallout of those events, and Ghostland is too. The plague besetting Ghostland is a nuclear one, and the ghosts themselves are a result of this terrible accident. In other words, even a film this superficially silly, in Sono’s hands, can’t help but be informed by the social anxieties and nuclear terrors that have so moved him in the past decade.

But as the film settles into its rhythms in the Ghostland, it also starts to drag with too little going on beyond a tour through production design. Sure, the unnamed hero has a few dreams that propel him forward — both narratively and toward his own redemption — and yes, this is all gearing up for a big finale, but an additional action sequence or two could have enlivened things in this middle going. Whatever else one might say of Sono’s films, they are rarely sedate, and so it’s surprising to watch one go this long without some bit of gonzo or kinetic excitement. When Prisoners of the Ghostland reaches its finale, however, it takes the form of a very worthwhile cowboys and samurai brawl that, while not among the best Sono action sequences, bears the director’s trademark energy and even has a few surprises up its sleeves. This is not either man’s best work, but it’s a good fix for those in need of one.

Originally published as part of Sundance Film Festival 2021 — Dispatch 3.

Comments are closed.