OK, so things don’t really vanish anymore: even the most limited film release will (most likely, eventually) find its way onto some streaming service or into some DVD bargain bin assuming that those still exist by the time this sentence finishes. In other words, while the title of In Review Online’s monthly feature devoted to current domestic and international arthouse releases in theaters will hopefully bring attention to a deeply underrated (even by us) Kiyoshi Kurosawa film, it isn’t a perfect title. Nevertheless, it’s always a good idea to catch-up with films before some… other things happen.

The Velvet Queen

One can forgive most nature documentaries for their straightforward methodologies; given the high production costs involved in sending film crews around the world and patiently waiting for organisms to do something that catches the eye, it’s understandable that most films opt for mass-audience appeal. While there are moments in, say, David Attenborough’s documentaries when explanations of on-screen visuals feel excessive, it’s a safer bet to over-explain than to leave viewers with contextless images. This industry standard makes Marie Amiguet‘s The Velvet Queen a modern marvel: it’s the rare nature documentary that’s both unconventional and largely benefits from ample talking. The film’s poetic title reveals itself to be more apt than the original French one, which translates literally to The Snow Leopard. Across an hour and a half, we follow wildlife photographer Vincent Munier and world traveler Sylvain Tesson as they hike the Tibetan Plateau, in search of the elusive titular animal. Much of the film, though, is about the process, and one that’s notably less physical or technical than mental.

The Velvet Queen’s most astonishing feat is how it recalibrates the viewer’s mind. There are constant reminders of our place in the world as we witness barren landscapes and feel the ostensible futility of Munier and Tesson’s journey. There’s a sense of smallness, yes, but more moving is an acceptance that the snow leopard may never be seen. “So not everything was created for the human eye,” we hear. It’s in this pondering that one considers the psychological aspects of filmmaking, how what’s present on screen is constantly in service of the viewer, that what’s present is what we presume should be seen. The Velvet Queen is instructive, then, in having viewers embrace the beauty of a mode of thinking where humans don’t have supremacy over the rest of the world.

There’s no better way to shake up one’s relationship between self and others than a real-deal trek into nature. The powerful solitude concomitant to such travels is lovingly captured across The Velvet Queen’s extremely quiet passages, in both illustrious wide shots of the terrain and close-ups of Munier and Tesson amid riprap. More surprising is how the score, provided by Warren Ellis and Nick Cave, is straightforward in its intention to evoke grandiosity, but nevertheless feels affecting — its presence acts as encouragement to embrace unknowability. All this philosophizing would have been enough to make The Velvet Queen a worthwhile experience, but it transforms from end-game to build-up when Munier and Tesson finally witness the snow leopard. The film and its final shots are profoundly moving because there’s so much gratitude we feel as viewers — a testament to The Velvet Queen’s ability to teach that the world around us, and any images of it, are legitimate gifts.

Writer: Joshua Minsoo Kim

The Death of a Telemarketer

Actor Lamorne Morris has made a career out of playing characters whose charm paradoxically lies in their disingenuousness. Nothing that comes out of the man’s mouth seems the least bit sincere, yet his delivery is so smooth, and his wordplay so dexterous, that one can’t help but be seduced even as all logic cries foul. Writer-director Khaled Ridgeway’s Death of a Telemarketer takes full advantage of that poisonous charisma, casting Morris as Kasey Miller, a God-level telemarketer whose gift for gab has made him a legend in the offices of Telewin, where he peddles phone, Internet, and cable TV packages to susceptible stooges across the country. The man is entirely unable to turn off the bullshit, whether he is conversing with envious coworkers, his harridan of a boss (Gwen Gottlieb), or the girlfriend (Alisha Wainwright) with one foot out the door. A contest at work will guarantee him a bonus of $3,000, which is conveniently the same amount of money he needs to pay back a loan company by the end of the day. Yet as fate would have it, Kasey is off his game for the first time in his life, resulting in a loss that drives him to desperate measures, namely acquiring the infamous Do Not Call list and attempting to make one final sale. Naturally, Kasey contacts the wrong person, an older gentleman by the name of Asa Ellenbogen (Jackie Earle Haley) who has no patience for Kasey’s lies, and who returns the favor by showing up at the Telewin offices and holding him hostage. Asa demands only one thing of Kasey: if he can convince a single person on the Do Not Call list to accept his apology on behalf of telemarketers everywhere, then his life will be spared. If not, he gets a bullet between the eyes.

There’s a kernel of a good idea here in that Kasey’s fate ultimately hinges on him performing a task that requires the utmost sincerity, but one that can only be accomplished through channeling a persona that traffics in deception. As is made painstakingly clear in the film’s opening minutes, Kasey cares little for the individuals to which he is selling, making one pathetic promise after another to people who largely cannot afford the services he is providing. And so, according to this profound relatability, Death of a Telemarketer plays a little like wish fulfillment, as anyone with a phone can relate to Asa’s frustration at these seemingly indestructible individuals who call at all hours of the day and care only for the potential dollar signs on the other end of the line. Unfortunately, Asa’s character is written so broadly that any sort of potential sympathy is dispensed with immediately. Instead, the film ultimately becomes a morality play, a tale of personal redemption for a protagonist who is forced to find his humanity in the most dire of circumstances.

If you think that sounds suitably dull, you’d be correct, and the majority of the film’s back-half is a two-hander between Morris and Haley, neither of whom are capable of selling the melodramatics the script requires of them, an irony seemingly lost on the filmmakers. Ridgeway’s direction is fairly straightforward, although he does occasionally use a disorienting wide-angle lens, which serves no purpose other than to draw attention to itself. An overreliance on utilizing shots of sped-up L.A. traffic to link together disparate scenes comes across as rather amateurish, as does the overly generic score. Morris is the best thing the film has going for it, his improv skills put to the test in nearly every scene, scoring laughs a not insignificant amount of the time, and certainly higher than the median that most performers can muster. But despite his successful batting average in this regard, he’s given precious little else to do for the majority of the film’s runtime, which seems to be spinning its wheels for long sections until its foregone conclusion. Death of a Telemarketer is ultimately all talk, little substance. It’s safe to say that Arthur Miller does not appreciate the shout-out.

Writer: Steven Warner

The End of Us

Those nostalgic for the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic will find much to like about The End of Us, Steven Kanter and Henry Loevner’s relationship dramedy that chronicles one recently-separated couple’s attempts to cohabitate after March 2020’s stay-at-home order. Everything that marked the beginning of quarantine is on full display: Tiger King, bread-making, copious amounts of wine, sudden unemployment, debilitating anxiety caused by fear-mongering news channels and social media feeds. It was a simpler time, one which not a single person alive would care to relive, especially as most of the globe is still desperately trying to regain a sense of normalcy in the face of continued catastrophe. It was inevitable that the re-emerging cinematic landscape would be inundated with movies tackling the pandemic in some shape or form, and it’s no surprise that those first out of the gate wield its specifics as novelty, a new wrinkle to tried-and-true formulas. Accordingly, The End of Us is a standard-issue rom-com with COVID proving the ultimate monkey wrench, as struggling actor Nick (Ben Coleman) and corporate executive Leah (Ali Vingiano) are forced to continue living under the same roof after a nasty break-up that coincides with the Corona-shit hitting the fan. Events follow a predictable path: petty squabbling leading to renewed feelings resulting from a night of binge drinking, which in turn of course leads to personal growth of both parties. Strike that, Nick attempts to improve himself, while Leah does stupid shit and regresses, but Kanter and Loevner don’t seem to recognize this, and so her arc feels muddled and incomplete, unless buying a dog signals maturity on her part — that detail is left unclear.

The filmmakers certainly stack the deck against Nick in the early going, painting him as some sort of immature man-child unable to properly communicate his feelings. But by film’s end, it’s the portrayal of Leah that seems borderline cruel, a bizarre choice that has the unfortunate hint of misogyny, no matter how unintentional it may in fact be. For their parts, Coleman and Vingiano actually exude a fair amount of chemistry, invaluable to a film of this nature, but their flaws, while realistic, also make them rather obnoxious company to keep for large stretches of the movie’s runtime. The question one has to ask when it comes to a movie like this — take note, more are surely in the offing — is: if you remove COVID from the equation, is this as effective? The fact that The End of Us is problematic even outside the specter of its pandemic trappings signals a flawed venture from the start. It’s the kind of film that will undoubtedly prove more interesting the further removed we become from March 2020, a snapshot of the minutiae that consumed and textured our isolated lives. But as a rom-com-styled portrait of a failed relationship, there isn’t a vaccine around that can save The End of Us. [Originally published as part of SXSW Film Festival 2021 — Dispatch 2.]

Writer: Steven Warner

The Gardener

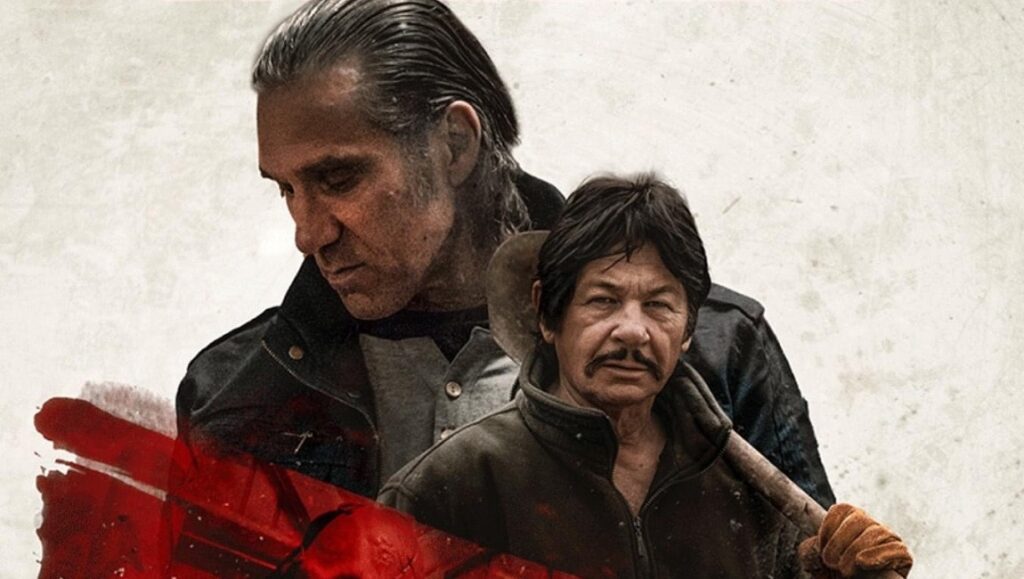

We’re in a veritable golden age of high-octane, low-budget DTV action flicks right now, with talented craftsmen like John Hyams, Isaac Florentine, and Jesse V. Johnson plying their trade here in the US, and guys like Julien Leclercq and Guillaume Pierre in France, amongst many others. Alas, there’s also always been a market for bottom-of-the-barrel garbage in the DTV scene, as aging stars cash easy paychecks and mysterious financial backers look for tax havens. All of which is to say that The Gardener, a new excremental flick that is soon to disappear into the furthest reaches of a streaming service near you, is less a feature film than a 90-minute money laundering scheme — one that somehow took three people to direct it (Scott Jeffrey, Rebecca Matthews, Michael Hoad).

If The Gardener has a reason to exist beyond the financial needs of shady Eastern European businessmen, it’s to showcase the (negligible) talents of Charles Bronson look-alike Robert Bronzi, a 63-year-old Hungarian cowboy who was “discovered” by a Spanish filmmaker who saw his face on a flier advertising a rodeo show. Whatever Bronzi’s real-life abilities might entail, acting is not one of them. Here, he is the titular gardener, maintaining the vacation home of a put-upon middle-aged couple and their teenaged children. he first half of the movie spends an interminable amount of time watching these people bicker, while Bronzi putters around in the background, occasionally muttering pearls of wisdom about the horrors of war and the joys of gardening (cultivating plants is cultivating life, you see). Unbeknownst to this extremely unlikable family, their deadbeat dad has placed the family business in a deep financial hole, and some mercenaries take the family hostage in the middle of the night to squeeze info out of him. Thank goodness The Gardener is here to clumsily take out each bad guy one by one, in a series of fight sequences not so much choreographed as embarrassingly glimpsed. Various stuntmen and women take turns wailing on Bronzi, who mostly stands there trying to pretend to look dazed before half-heartedly delivering a tepid punch or kick that sends his opponent flying to the ground. No-budget genre legend Gary Daniels shows up as the head honcho bad guy, who walks around showing off his sculpted physique and eventually goes mano a mano with Bronzi in a ludicrous final battle that finds both men moving so slowly you would be forgiven for thinking they were either underwater or trapped in molasses. Avoid at all costs.

Writer: Daniel Gorman

The Hating Game

The Hating Game was best-selling author Sally Thorne’s debut novel back in 2016, and if the Internet is to be believed, it has a wildly rabid fanbase, many of whom have been foaming at the mouth for a film adaptation for years. Curious, then, that the movie was independently produced and picked up for distribution by a studio that balances its streaming ventures with theatrical distribution. Perhaps they sensed that the target audience would rather grab a glass of wine and watch it on the couch than venture out to the theater in the middle of a pandemic. It’s more likely that they winced their way through an initial screening and thought, “Hey, brand recognition.” Fair enough. But that grudging respect does not extend to the film itself, an abomination that tries to be sexy, raunchy, sweet, and spiked, but only succeeds in being abhorrent.

A battle of the sexes in which the only winner is Thorne’s bank account, director Peter Hutchings’ The Hating Game presents the story of Lucy (Lucy Hale) and Josh (Austin Stowell), two individuals, as attractive as they are obnoxious, who work at a New York City publishing house. They share the same job title — Executive Assistant — although they also appear to be practically running the entire company themselves, which does indeed check out and proves to be the most realistic aspect of this movie. What was once a prestigious publishing firm has fallen on hard times, and as the film opens, it has been forced to merge with a competitor that favors “tell-all books about sports stars,” which is certainly a niche. The merger has forced sensitive artists to mingle with frat bros, the results being about as disastrous as that sounds.

Lucy and Josh, meanwhile, have a strictly hate-hate relationship; he is anal and domineering, she is sunny and lets people walk all over her. Except that she’s not really that way at all, because as is shown in numerous scenes, she is confrontational with Josh to the point of verbal abuse. Writer Christina Mengert seems to be under the impression that her dialogue is of a lineage with the likes of His Girl Friday in its flirty, fast-paced banter and caustic wit, but what it more resembles is a particularly barbed episode of Hangin’ With Mr. Cooper. A deluge of dialogue delivered at a breakneck pace does not inherently breed cleverness, something we should’ve learned from the likes of Aaron Sorkin ages ago. Naturally, the two are secretly attracted to one another, but continue to play this schoolyard game because they are nothing more than adult-sized babies who act in no way, shape, or form like actual human beings. Both end up going after the same promotion, which stirs up fiery emotions that match their hidden libidos and ultimately cannot be contained. But are the two simply gaslighting one another in an effort to throw the other off their game? In a nutshell, the film proceeds in this way: they hate-flirt, dance around sex, and suspect each other of manipulation on a maddening loop.

Josh, it must be said, is criminally insane. Lucy is not wrong when she describes him as “American Psycho.” He treats her like full trash until suddenly the script decides he shouldn’t, but then ten minutes pass and he’s an asshole again. At one point he tells Lucy that she is not allowed to kiss him again until she makes out with another dude just so he can properly believe her when she utters the words, “No one kisses like you,” a line he forces her to say. He then later professes his undying love after a single date. The film also weirdly portrays the toxic masculinity and sexual harassment present with the publishing offices as borderline comical, until suddenly it realizes it is 2021 and throws in a line about possible prosecution. And then the batshit ending rolls around and finds the fractured couple reuniting seemingly because Lucy gets her way, which is a fairly insulting bow to put on this. Add to that the fact that Hale and Stowell have zero chemistry, which is what you get when you cast two of the most charisma-free actors working today, and you’ve got a final product that’s somehow worse than the duo’s last collab in Blumhouse’s big-screen adaptation of Fantasy Island. The Hating Game is appropriately titled, then, in that it’s sure to inspire that titular emotion in plenty of viewers (one assumes The Crying Game would also have been considered if not already spoken for). For many, this film will be a strong argument to swear off straight white people for good.

Writer: Steven Warner

Comments are closed.