Coma

There have been a number of “lockdown movies” since the outbreak of Covid, and most of them have been unfortunate affairs. While it’s true that limitations often spur creativity, too many filmmakers, both narrative and experimental, have struggled to articulate their own unresolved feelings of isolation and despair, with the results too often veering into narcissism. If Bertrand Bonello’s Coma is the first film to find something genuinely bracing to say about the Age of Covid, it’s probably because he mostly avoided exploring his own experience. Instead, Coma is a work of remarkable empathy, in which Bonello attempts to understand the psychology of lockdown from the perspective of his 18-year-old daughter Anna.

Bonello bookends Coma with rather direct, first-person addresses to his daughter, wherein he explains his frustration as a parent, witnessing Anna going through the loneliness and anxiety of the pandemic but being unable to really help her. As he explains somewhat obliquely, this is really just a more attenuated version of every parent’s experience, of seeing your child move into a world that is decidedly not yours, one you cannot control and often cannot understand. In a sense, Coma is Bonello’s attempt to create concrete metaphors for both his daughter’s psychological states and his own inability to fully grasp them.

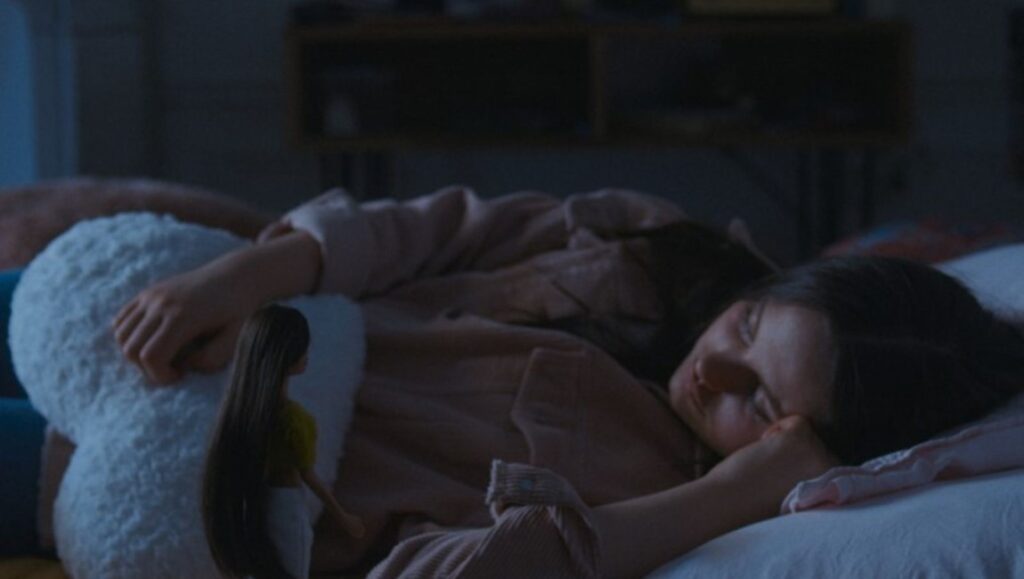

An unnamed teenager (Louise Labeque) is confined to her family’s apartment during lockdown, but we never see anyone else in her family. Her encounters with the larger world are all highly mediated. She has a Zoom call with friends. She makes up a complicated soap opera with her old Barbie dolls. And she becomes increasingly enamored with a YouTuber named Patricia Coma (Julia Faure), who claims to be providing guidance on how to improve your life. Patricia comes across as a bizarre combination of Jordan Peterson and pop star/performance artist Poppy, perhaps as envisioned by Duke of Burgundy director Peter Strickland. She is severe, vaguely goth, always appearing in isolation to provide quasi-Deleuzian advice on the dissolution of the self. Her primary objective is convincing her viewers that free will is an illusion, that we are all passive vessels for a predetermined course of events.

Bonello perfectly captures the anxiety each generation feels with respect to the next one, their own children. Not only have we brought them into a world on the brink of collapse — ecological, economic, political – but we cannot offer them any tools to navigate this world. Covid, then, can seem merely an accelerant for an apocalypse already well begun. Adding to our fears is the fact that the Internet has assumed the role that we cannot. We have no answers, and into that void step any number of gurus and influencers, promising to make sense of the universe, through heightened materialism, conspicuous minimalism, neo-fascist fantasies, and so on.

Bonello wisely keeps Patricia Coma’s overall agenda ambiguous. And perhaps most tellingly, she eventually loses the plot herself, admitting that like every other adult in the teenager’s life, she is at a loss for the answers. The only place the young girl seems to experience connection is in her dreams, when she is transported to a limbo dimension called the Free Zone. Patricia appears here as well, as a guide through this liminal space filled with unseen threat. Coma suggests that people forced to become young adults in this era are aching for some palpable reality, but often confuse affect with danger. As the girl and her friends chat about their favorite serial killers, we see that mortality is always hovering in front of them, as an opportunity to feel something at long last.

Bonello has described Coma as a film about a teenager who “has a special power: she can bring us into her dreams — but also her nightmares.” But of course, he is really describing cinema itself, a mechanism for visualizing our hopes and fears, in the hope that making them public property could serve as a point of human connection. Bonello obviously understands that the cinema, as such, is over – that this is not how our children share their dreams. Coma offers no solutions, but suggests that even if parents and children, cinema and TikTok, free choice and the algorithm, represent incommensurate worlds, forging even a flawed connection between them is our own hope against complete alienation.

Writer: Michael Sicinski

The United States of America

James Benning’s The United States of America (2022) opens with a shot of Heron Bay, Alabama. With its muted landscape and dull blue sky, the space emanates an unmistakable sense of loss. Lining the horizon are the roofs of houses — one a dusty pewter, another a chestnut brown — and foregrounding the image are the dilapidated remains of a wooden structure. This doesn’t feel like the same country that defined The United States of America (1975), one of three shorts Benning made with Bette Gordon. In that film, the two mounted a camera in the back of their car to document a road trip from New York to Los Angeles, the windshield becoming a portal into the richness of America’s environs. With the two always in view, and with the vantage of a passenger, there was an intimacy and casualness to it, something aided by the constant use of dissolves. This spiritual sequel is more austere, working in a familiar structural mode that Benning has employed in the decades since. Each stationary wide shot lasts 105 seconds and is preceded by the name of the city and state being depicted. All 50 states are accounted for, along with the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, but there is no continuity, no journey that lands in front of the Pacific. If there was a desire to capture the trek from “Sea to Shining Sea” back in 1975, then Benning aims for the particulars in that Johnny Cash song here; “the swamps of Okefenokee” and “Hibbing, Minnesota” are locales we indeed encounter in these 100 minutes. Now more than ever, Benning wants specificity.

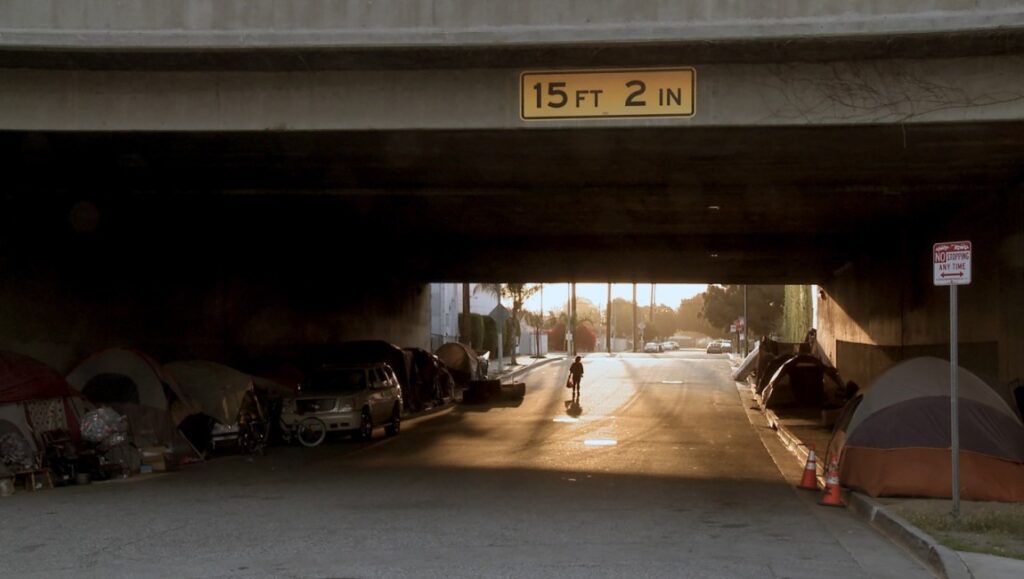

That specificity arrives in broad strokes: each city and town is lovingly captured, though the time we have to sit with each shot is relatively short. Being abruptly vacated from one state to the next is a pointed maneuver, however; one of the ideas presented here is that one can never truly soak in the entirety of the nation’s diverse environments, be they the barren lake in St. Elizabeth, Missouri or the snow-topped trees in Stemple Pass, Montana — one of the only shots animated by movement, the snowfall looking extraordinarily dazzling. This brevity is also, to hearken back to the 1975 film, in line with the transitory spirit of a road trip. Still, some images are striking enough as to be indelible: Little Eagle, South Dakota is almost hallucinatory with its slow-moving clouds, while Wilmington, California has this lovely golden sunshine tucked underneath an overpass. The United States of America (2022) is, at the very least, a feast for the senses.

Just as sound played a crucial role in the Benning and Gordon film, so too does it elevate this new one to something beyond pretty images. Back then, the two used the radio to channel the moods and ideas of the time: talk of the Vietnam War, a song from Deep Purple. Most notable was the repeated use of Minnie Riperton’s “Lovin’ You,” which appears only once here amid the clouds of Cleveland, Ohio. It’s low in the mix, however, and often hard to hear alongside nearby chatter. It feels odd, like talking with a former lover who’s all but a stranger now. In that aforementioned shot of Alabama, one hears the Carpenters’ “(They Long to Be) Close to You” below the ostensibly diegetic sound of the space. That track’s wistfulness is carried over to Woody Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land” in Minier, Illinois and then to Riperton’s. Traveling from state to state, there’s a creeping understanding that any love one has for America ought to be checked for being misguided. The most subtly impactful song arrives in Arecibo, Puerto Rico. We hear Buena Vista Social Club’s “Dos Gardenias,” a track that may sound fitting on the surface. The Cuban group’s self-titled album was one of few instances where Latin American music found major success in the States. Its presence here is a reminder of Americans’ ignorant assumptions that all countries in the Caribbean or Latin America are the same. Even more, one recalls Puerto Rico’s status as a U.S. commonwealth and America’s imperial pursuits of both Cuba and Puerto Rico; the former has generally been the more desired of the two, especially in its comparative depictions by media. America always wants what it can’t have.

There are more direct references to American horrors across The United States of America (2022). Benning chooses a cotton field for Fayette, Mississippi, and the audio we hear is from civil rights activist Stokely Carmichael. He speaks firmly, “You have to build a movement so strong in this country that if one Black man is touched, every Black man will rise up and let them know they’re not gonna tolerate it.” An interviewer questions him with an incredulous tone, bringing up the supposed terror of “riots.” Carmichael swiftly corrects him, “I call them rebellions.” Later in Hanksville, Utah we hear someone discuss Manifest Destiny, the displacement of Indigenous people, and how they were confined to reservations. In both these moments, we remember that the wide expanse of America isn’t a freedom available to everyone.

Benning drives his point even further in the film’s conclusion. A parking lot in Milwaukee, Wisconsin is soundtracked by Alicia Keys’ cover of John Lennon’s “Imagine.” For a song so hackneyed and staid, Benning manages to draw poignance from its content. “Imagine there’s no countries,” we hear, reflecting upon the tragedies that characterize his own country. The song cuts out right after “imagine all the people” and right before “living life in peace.” When we land in the final state of Wyoming, the image of a barbed wire fence telegraphs the hatred, racism, and xenophobia that is the reality for many who live across America; peace is, irrefutably, not here.

In an astonishing finale, the end credits upset everything we think we have seen. There’s an impressiveness to the deceit he employs, and it’s a delight to see Benning deploy a longform gag, but most important is how it highlights the truth underlining the entire movie: The America many know and love is rarely one that’s depicted honestly. One thinks of Benning’s other film with America in the title, American Dreams (Lost and Found). The multiple narrative devices in that film complicate any neat image of the country, and one can see both United States of America films as their own separate strands of America to mentally superimpose. It becomes clear: In reusing the same title as his decades-old film, Benning forms a necessary dialectic between America’s scenic beauty and its sinister underbelly. “Lovin’ you, I can see your soul come shining through.”

Writer: Joshua Minsoo Kim

Jet Lag

In many respects, Jet Lag feels like a recognizable follow-up to Chinese director Zheng Lu Xinyuan’s Tiger Award-winning The Cloud in Her Room. There’s black-and-white photography and time jumps, languid pacing, and a fabulous shot that centers on pubic hair. But beyond such superficialities, this is a film that’s far more confident in its slipperiness, willing to let loose ends remain as is. This quality is evident from the get-go: Zheng Lu discusses the film — the screen entirely pitch black — and it’s noted that there’s a lack of a “main character,” a move that’s pinned to Zheng Lu’s reluctance to take on a lead role. Jet Lag’s simultaneously convergent and divergent narratives ensure this wisely remains the case.

There’s far more going on in Jet Lag than its intimate documentarian mode suggests. Part of the film documents the director and her girlfriend Zoe in Austria in 2020, the two forced to stay abroad due to a Covid lockdown. Footage also dates from a couple years earlier, when the family attended a distant relative’s wedding in Myanmar and used the opportunity to learn more about their expat patriarch, Zheng Lu’s great-grandfather. Then there are moments closer to the present, when Zheng Lu and her girlfriend are back in China. These moments lead us once again to Myanmar, but now with a focus on its ongoing political turmoil. Jet Lag has these varying narratives but the overall feelings and ideas are befitting the film’s title: one’s identity — individually and corporately — is always in flux, and there’s discomfort and revelation found in being out of sync with both time and place.

Jet Lag utilizes different film textures and modes as a way to bolster overlapping moods. There are screen captures of Google Maps and cracked phone screens, both serving as tools for learning more about Myanmar. This distancing, borne from satellite imagery’s artificiality and obfuscated digital text, makes this desire for connection all the more palpable. Even more affecting are the still photographs that define the beginning of the film, which is something one recalls when we see a photo of Zheng Lu’s great-grandfather much later on. On his portrait is a date, and it becomes a source of confusion — is this when he died, or is this when the photo was taken? Images are understood as insufficient time capsules — they can only reveal so much.

Most of Jet Lag is shot on a Sony DV camera, and its murky footage houses the most riveting images. They are slow-revealing paradoxes: sensual and banal, hypnotic and quotidian. In the middle of the film, Zheng Lu flips her camera upside down while on the road, and the result is both more disorienting and freeing than expected, as if its own kind of relief from the confusions defining the film. At one point, we watch as a simple exercise — raising a leg while lying down on one’s side — leads to momentary blockage of the sun, the change in light feeling like a necessary reminder of one being alive. At others, nude bodies are channels of both love and boredom. Such enigmatic images are spiritually linked to the most poignant passages in the film: English-language classes where friends share about their lives. Here, through the act of speaking in something other than their first language, these people are comfortable with revealing highly personal stories. It’s this excuse to learn that’s key. We don’t ever learn too much about Zheng Lu’s great-grandfather, and indeed her cousin notes that never having met him in person means it’ll stay that way. But Jet Lag, in its curiosity-driven filmmaking, understands that it’s only through life’s mysteries that we are driven to learn more about ourselves.

Writer: Joshua Minsoo Kim

Afterwater

“Swimming in lakes and ponds one also drinks out of, and finding that everything that one sees is intimately linked to one’s body movements, constituted a kind of alternative to the physically passive position of the cinema spectator — and a hint of a realm that lies outside of our industrial civilization,” wrote Fred Camper in 2003, describing how his many wilderness trips taken throughout the ‘70s were his “deepest source of spiritual sustenance” over the cinematic likes of Brakhage, Gehr, Kubelka, and Markopoulos. Dane Komljen’s Afterwater, likewise, is probably the closest “film” — an odd descriptor for a work that features Hi8 footage and was partially shot on a digital camera — produced in some time to successfully emulate this liberating relationship between subject and nature. It’s comprised of three disparate segments, each one less concerned with narrative than the last: the first is a proto-Angela Schanelec riff, set in the present, and with two awkward biology students reading, swimming, and camping near Lake Stechlin in Brandenburg, occasionally spouting lines from American limnologist George Evelyn Hutchinson’s A Treatise on Limnology — all while the densely vegetated landscape continuously threatens to consume this nameless duo. The second takes on a more distant, documentary-like approach, seemingly emerging out from the past to provide a more global context for Komljen’s experiment (filmed at a lake in Zamora, located in Northern Spain). The avant-garde finale — which is easily the most exciting section, at least on a moment to moment basis, simply on the strength of its extremely garish, “deep-fried” videocassette visual aesthetic — drops any pretense at establishing a clear linear progression between each portion, existing in a space removed from an established time zone or geographic location; three nameless entities, once again, simply exist amongst an environment of constant alteration, grappling onto one another’s bodies with a slow, precise rhythm straight out of the physical theater (this one, on its own formal merits, feels like it would be right at home in Collectif Jeune Cinéma’s vast collection).

If this at all sounds a bit nonsensical — and to a degree, on a surface level, it certainly is — then perhaps some relief will be drawn at hearing that Afterwater’s greatest strengths lie in its impeccable textural details, not its deadening thematic interests: the mirroring, almost reverberating lakes these languished bodies always seem to be bobbing in and out; the floating poppies that litter the sky like small dust particles floating around a living room during cleaning day; the bright crimson roses of the second segment; and, perhaps most interestingly, the deteriorating grain of the camcorder-shot third. This is to say that the best approach to take toward this material is in a loose, atmospheric sense, almost like an art installation; here, Komljen proposes that once you free your body from the confines of commercial cinema, you can thus truly free your mind to the great ecstasy of heightened perception. While that’s a bit of a lofty goal considering the general shapelessness of the final product, its advocacy for a body-minded cinema — especially in regards to the aforementioned visual character of the feature — are refreshing in a world dominated by straightforward thought.

Writer: Paul Attard

Call Jane

Call Jane, the directorial debut of Carol screenwriter Phyllis Nagy, opens with something of a feint. In a near mirror of that film’s first sinuous tracking shot, complete with pleasingly warm 16mm, it follows Joy (Elizabeth Banks) as she strides through a hotel lobby, passing the party that her lawyer husband Will (Chris Messina) is attending, before walking out onto the street to find a police line and the shadows of Yippie protesters in the distance: the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago and the ensuing chaos are literally just around the corner for these relatively sheltered suburban residents.

However, Call Jane isn’t about strictly the collision of culture and counterculture. It belongs, broadly speaking, to the recent resurgence of abortion dramas which includes fellow Sundance-Berlin selection Never Rarely Sometimes Always (2020, Eliza Hittman) and Golden Lion winner Happening (2021, Audrey Diwan). But Joy’s search for an abortion, prompted by a life-threatening condition during the first trimester of her pregnancy, forms a surprisingly minimal part of the film. Requisite attention is given to the board of doctors who refuse to grant a termination on probability grounds and the furtiveness required to obtain the money, but the screenplay by Hayley Schore and Roshan Sethi is refreshingly clear of the moral dilemmas and twists of fate that so often characterize this specific subgenre.

Instead, Call Jane finds something of a utopia within this milieu. Joy gets her termination through the Jane Collective, a real service in the Chicago area that provided discreet abortions, complete with a hotline and, at least initially, a dedicated but overcharging doctor named Dean (Cory Michael Smith). Leading the charge is Virginia (Sigourney Weaver, given several substantial showcase scenes), honed from decades of aggravating activism, who presides over a motley crew of women from different walks of life assembled for this single purpose. The rest of the film is as much dedicated to Joy’s growing fascination and involvement with the program — and her growing frictions with her husband and daughter Charlotte (Grace Edwards) — as it is with the internal dynamics and multiple viewpoints at play in the collective.

A good deal of Call Jane’s charge comes from this interplay, the respect paid to the fundamentally good intentions of almost every major character that nevertheless does not shy away from the limitations of clandestine operations and the day-to-day problems, from the number of abortions that can be allotted per week to the prohibitive $600 cost. Joy — and Banks, who turns in a strong and cagy performance — provides a useful viewpoint, not only because of her considerably more privileged vantage point, but also because of her tenacity and latent domestic frustration that finds its outlet through the Jane Collective. Innovations pop up throughout the film: Joy learns how to perform the abortion procedure herself, the little cards of information from applying women are supplemented by an answering machine. But the focus remains on the people over a relatively brief period, with taking deep interest in both the lively, ping-ponging debates within the group and the more uneasy, coded interactions that Joy has at home, captured most vividly in a scene with an undercover police officer (John Magaro) who ends his interrogation by asking Joy to contact “Jane” on behalf of his friend.

Call Jane’s overall outlook, and especially its post-Roe v. Wade epilogue, can certainly come across as overly satisfied and tidy, but Nagy’s facility with actors and camera movement ensures that this proceeds with assurance; in many ways, the relative lack of dire conflict acts as a benefit, making the ideological battles come across with greater weight. And there’s something oddly lovely and resonant about Joy’s final decision, its own form of compromise that comes with a recognition that most individuals are destined to follow a certain calling, but that it doesn’t prevent one from helping the work of others.

Writer: Ryan Swen

Comments are closed.