Fiddler’s Journey isn’t much more substantive than your average love letter doc, and suffers from an ill-conceived late-film detour.

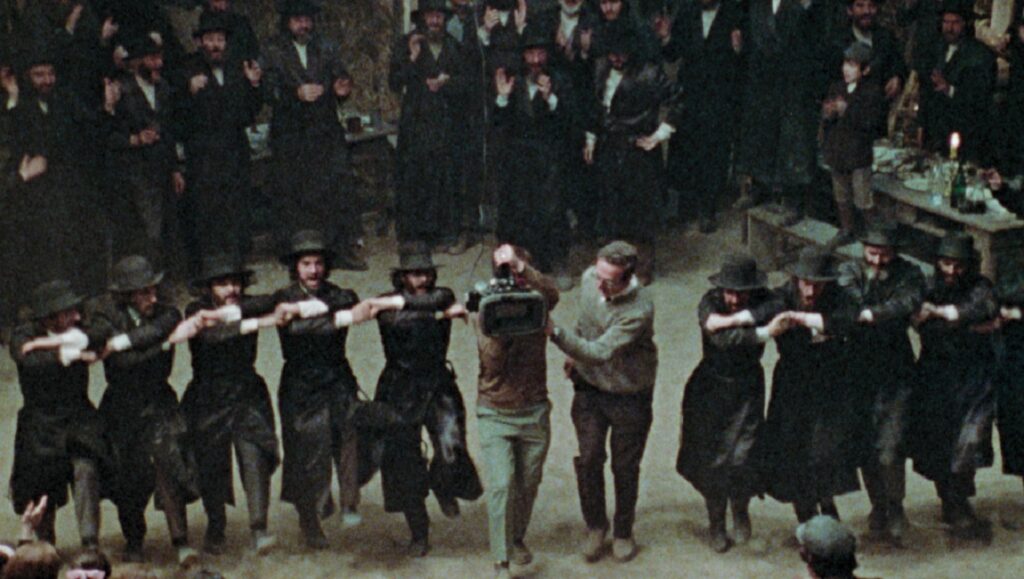

Daniel Raim’s chronicling of the pre-production and production processes of Norman Jewison’s Fiddler on the Roof is a meagerly informative expositional work that can’t quite jettison those industry-pushed aspirational faculties so often poured upon the labor behind the making of our classics. Fiddler’s Journey to the Big Screen is less a film about the work that is Fiddler — the history and peoples it has on offer — than a squabbling profile piece on Jewison, himself, in conversation with piecemeal anecdotes from the production. From discussing the process of location scouting in the former Yugoslavia to Jewison’s reminiscences on his late-teens — where an ignorance of segregation policy in the southern states saw him sitting in the back of a bus and then exiting in some form of bewildered protest — there’s quite simply not much focus to be found in the documentary.

Talking heads walk us through an oral history, everyone kvelling, the miracle and brilliance of the film’s production a nostalgic joy, but it’s frankly unclear what viewers are to do with these off-the-cuff sentiments. The film itself, and so presumably Raim as well, seems as struck in love by the work that is Jewison’s Fiddler as any of the subjects contained therein — that’s not to say this writer isn’t likewise enamored, but that doesn’t preclude including even an inch of scrutiny, right? The question, then: is being a love letter enough to justify the film’s existence? Suffocating, contemporary work-ethic discourse is the insistent campaign that seeks to shirk union-centric collectivization against the exploitation stemming from above-the-line. What is pushed into the mainstream psyche is an alternative narrative that sees film working, its physically demanding labor as an idealism: an “aren’t you lucky to be here?” mentality which creates an obfuscation between working conditions and the emerging class of film workers. Do we have any utility for a puff piece on how wonderful it was to work on set, a space historically rife with horror stories and often a lack of basic decency? In this sense, does such “art” not subliminally play out as a form of propaganda cloaked behind our love affair with the major motion picture?

More problematic here is that the film’s coda weaves in needless tangential subject matter, discussing Israeli reaction to the film. Jewison name drops, and seemingly bestows an air of greatness and mystique onto, Golda Meir and David Ben-Gurion, two political figures with robust backgrounds of incredible hatred, violence, and racism. That’s not to accuse Raim’s film of the racism that these individuals represent, but certainly it plays into the very wrong and conditioned Ashkenazi identity politic of one’s innate belonging and familiarity with the state of Israel. If there is something Fiddler’s Journey can undoubtedly be accused of, it’s the grotesque and ahistorical initiative of normalization. It reads, after all, as rather insidious to tie this very deeply specific cultural history, as depicted in Fiddler, of Eastern European Jewishness to Israel so nonchalantly. Israel is, of course, a state founded on an ideology of Hebrew supremacy, historically leaving the Yiddish communities behind during the Holocaust, only to take in what remained after so much forsaken blood had already been spilt. The British Jews who took part in colonizing Palestine would very articulately pronounce their dismissiveness and rejection of the Yiddish-speaking Jewry from within the Pale of Settlement and Prussia. And so, again viewers are forced to wonder, what is the purpose of this concluding detour? If it’s an intentional redirection, it’s an offensive approach, and if it’s tactlessly incidental, then it deserves the indictment of irresponsibility, lacking insight into proper Jewish history, that very story and soil from which Fiddler is made. Upon taking in these politically dubious facets of the work, it’s unclear what to think as the credits roll. What is gained from the cutesy, informal, and mostly directionless story that surrounds the production of Fiddler on the Roof? Raim’s film fails to offer anything further than a transient romance between Jewison, his cast, and an audience we’re only left to imagine ourselves as.

Comments are closed.