Cane Fire is a kaleidoscopic portrayal of white supremacy’s brutal legacy and a challenge to the enduring colonial myth of Kauaʻi.

In the investigative documentary Cane Fire, the personal is the political. Director Anthony Banua-Simon’s journey starts as a straightforward quest: to uncover lost footage of his great-grandfather, Alberto, in Lois Weber’s 1933 film White Heat (also known as Cane Fire) shot on the Hawaiian island of Kaua’i. He was an extra in that Depression-era plantation melodrama, as many non-white inhabitants have been in the succeeding decades of films shot there. Alberto was a plantation worker and more significantly a labor activist. It’s this that proves the genesis of Banua-Simon’s fascination with the island’s history, with the various engines of capital that obscured that history, and with the Indigenous and working-class residents battling to preserve that history — and themselves. Cane Fire juggles these elements to construct a multi-faceted exploration of the island and its peoples, crucially taking aim at the encrusted myths that displace the truth of this “paradise” in the American imagination.

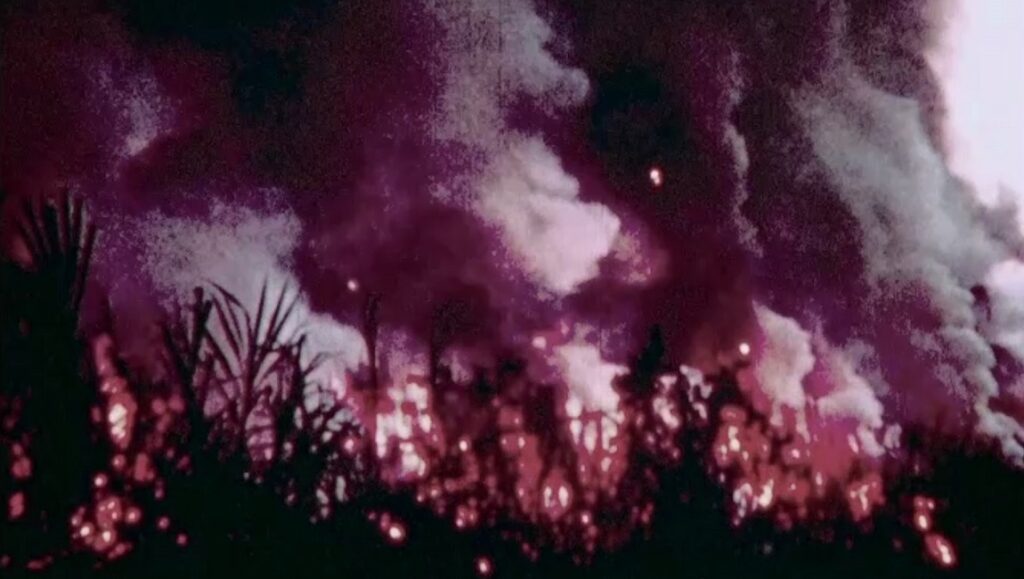

Banua-Simon’s film operates on numerous levels, particularly as a piece of media criticism. The Hollywood machine played an integral role in crafting the idea of a Hawaiian island most outsiders hold: a laidback, sun-kissed tropical wonderland that bent itself to the will of the invader. Jungle Heat, Donovan’s Reef, Miss Sadie Thompson, South Pacific: Banua-Simon unpacks a canon of South Seas fantasy descendants, often splicing montages of oppressively cheery, eerily beautiful sequences plucked straight from some technicolor hell. Non-white residents abound as set dressing, human props — typically servants, ciphers, or slain bodies — to bolster the racist façade. Banua-Simon can be clever in his editing, at times using a film clip to starkly contrast a blighted reality, other times letting it represent a white resident’s delusions. He adeptly seeds a sense of mounting psychological horror, a palpable dissonance that fills the negative space in his shots and strains the weary faces of his native subjects.

Admittedly, the filmmaking can feel pedestrian, at times even amateurish. Yet the inexpensive, on-the-ground feel highlights Banua-Simon’s honesty in the face of glossier narratives. He traces his subjects tenderly, elevating them to the level of protagonist when they are featured in frame. The very plainness amplifies the realness of what’s being observed in the cluttered homes and deforested clearings. His homemade stylings lend the film an instant relatability that sets the table for its moments of stirring intimacy.

Cane Fire presents the power imbalances involving labor as this story’s original sin. Banua-Simon takes pains to show how even as the island’s dominant institutions have cosmetically evolved — from plantations to films and resorts and then real estate companies — things are much the same for the non-white locals. Often his subjects speak of hosting multiple generations in their homes. One scene spotlighting Habitat for Humanity’s homebuilding efforts reveals that all of the recipients work in service positions. The labor organizers (one being his grandfather) that the film intermittently cuts back to are the generational connective tissue between the sugar workers of old and private club groundskeepers of today. Banua-Simon layers his information circuitously, at times confusing our sense of specific chronologies. Yet we can imagine this dizzyingly circular arrangement to be precisely his intent, crafting a kaleidoscopic portrayal of white supremacy’s brutal legacy. Cane Fire represents whiteness as a blind, disaffected self-importance manifesting variously along a spectrum of low to high direct harm. The family that considers a home shown by Kaua’i Tropical Properties doesn’t commit the same violence as the agents of the state ejecting native activists off their ancestral grounds, but still they share a continuum, an organized linearity that parallels the historical thread connecting Kaua’i’s early natives to its contemporary neocolonial subjects. When he shoots the island’s Indigenous residents — some of whom being his own family — he depicts their poverty and struggle frankly. He grants them the space to laugh and reminisce, speak bitterly on their condition and grieve. The film achieves a sense of reclamation on their behalf while remaining unflinching in depicting the totality of what oppresses them.

Toward its end, Cane Fire includes a transgressive sequence of comedically violent retribution, but opts to conclude on a more ambiguous note. To some this may register as a bit unskillfully inconclusive, yet Banua-Simon connects enough dots to make his point land. The myths he’s competing against will continue on after the credits are done, but now they will no longer go entirely unchallenged.

Comments are closed.