Funny Pages frequently approaches incisive commentary about youth’s quest for validation, but it ultimately ends too meekly and with too little introspection.

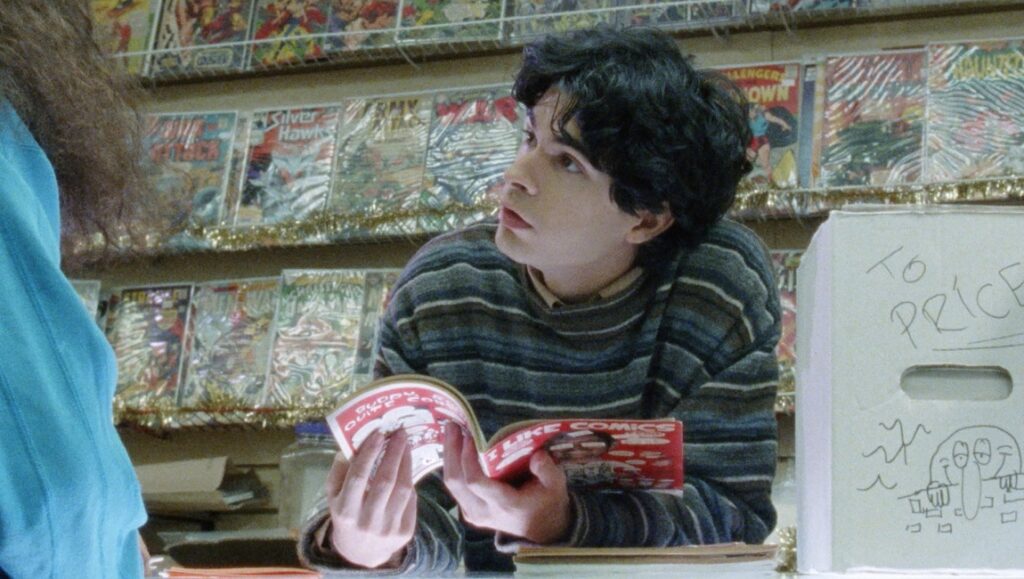

Life comes at Robert, the scraggly protagonist of Owen Kline’s sort of humorous, sort of unremarkable Funny Pages, rather quickly. After the sudden death of his artistic mentor (which he may or may not have inadvertently caused after storming out of an “intimate” drawing session), he decides to drop out of college, moves out of his parents’ lofty living quarters in Princeton, and abandons his dreams of going to art school — all in the misguided hope that these rougher living conditions will produce a more honest portfolio, and also provide Robert the necessary authenticity needed to be a true starving artist (and not one of those losers who sold out to make superhero comics). His irrational commitment to a life of misery produces few tangible results — his technical abilities don’t improve much, nor does his line work — but instead only many small headaches. There’s his new crib located all the way out in Trenton, which is really just a small, sweltering basement that he shares with two other grown men; the monthly rent for this “shit hole,” as Robert later describes it, is $300, and the measly temp job he later procures through sheer luck (typing assistant for the public defender) barely covers even half of that.

Yet even through all of this, we’re never asked to sympathize with Robert or his inherently bullshit struggles; Kline seems all too aware of how nauseating the film would be if we were asked to care about any of this, so he wisely cranks Robert’s abrasiveness up to 11 and allows a certain queasy mixture of cringe and schadenfreude to take hold. There’s a truly embarrassing level of preciousness that every twenty-something believes about themselves, where they’ll act rebellious one minute then cry that nobody is helping them out the next; the fact that Robert always knows that he has a safety net to catch him whenever he’s done playing pretend grown-up makes his behavior all the more pathetic, reaching a point of hysterical fanaticism when he meets the nasally-voiced Wallace (Matthew Maher), a deeply touched illustrator (a “color separator,” as he likes to clarify) who Robert sees as the platonic ideal for the type of self-hating narcissism he likes to casually display to any and all who genuinely care about his well-being.

It’s in this troubling dynamic where Kline comes closest to capturing something truly discerning about youth and their never-ending quest for personal and professional validation, where Robert continues to pester Wallace into critiquing his work, even after the comics veteran has clearly displayed some outright assaultive tendencies toward others. Wallace ultimately obliges, which results in a lot of verbal aggression lobbed in Robert’s direction for creative choices that seem sophomoric or unmarketable to him. It’s a vicious cycle, one that seems almost eternal as young, unestablished talent continue to seek advice from elder statesmen who’ve long since stopped caring about the craft as a whole. But it’s also one that Kline couches in little actual introspection: right when things begin to get interesting — when tensions begin to fly, alliances start to crumble — the film meekly ends, choosing to go out on a note as unremarkable as our lead hero’s journey. It all comes so quick; then, suddenly, it stops.

Comments are closed.