Drifting Home can be plagued by its narrative convention and visual monotony, but it’s also a charming portrait of emerging adolescence that will please plenty of genre fans.

At age 34, Hiroyasu Ishida is quickly establishing a penchant for the strangely, sweetly whimsical. His work in the anime industry spans over a decade, directing numerous shorts while juggling writing credits on some and animator credits on many. His critical darling Penguin Highway, released in 2018, found Ishida replete with the feature-length space to further delve into the themes cropping up across his oeuvre. Back in April, Netflix announced a multi-picture partnership with Japan’s Studio Colorido, the studio responsible for Penguin Highway as well as Ishida’s latest film, Drifting Home. Ishida here feels emboldened by this partnership, seemingly intent on mining some Miyazaki-esque magic from this solid tale, wielding the adventurous potential of dreamscapes to lend epic weight to a metaphor for overcoming change, communicating honestly, and accomplishing self-forgiveness. While its generic aspects and formal simplicity hinder it from arriving near any sort of greatness, its undeniable heart is a more than capable hook that will keep it firmly in audiences’ good graces.

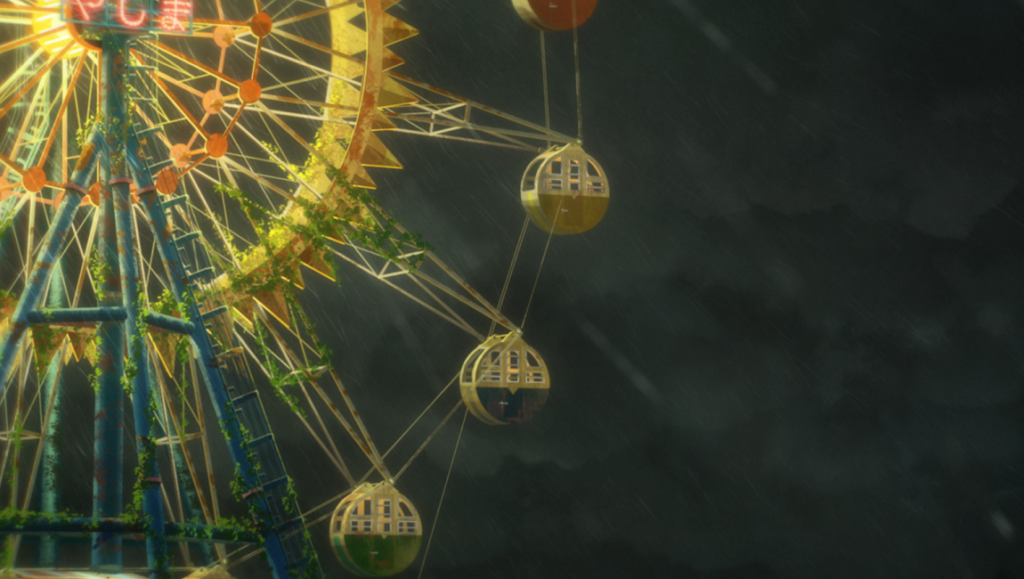

Soon-to-be sixth-grader Kosuke stoically reels from the imminent demolition of the apartment complex where he spent his earlier childhood years with his grandfather. His fellow classmate and friend, Natsume, used to live with the two, and the news of the building’s demise deeply affects her as well. One of Kosuke’s friends convinces Kosuke and another to join his exploration of the demolition site. The three find Natsume camped out in the complex, before two other girls from their soccer club get involved in the shenanigans. After a heated confrontation over one of the grandfather’s prized mementos, an accident seemingly triggers the group’s transportation to a parallel realm, leaving the six marooned in the building as it drifts across an endless sea. Together, they must overcome their internal divisions and demons as their odyssey grows increasingly dangerous.

Stripped of its visual flash and sentimental strengths, the narrative glides on rather conventionally. The seiyuu voicing the children carry the load in keeping the characters interesting, as they otherwise function pretty archetypically. The kids bicker and bond for intermittent spells before a new obstacle pops up that they must surmount. Confined largely to the apartment complex’s roof and a couple rooms, the setting itself is static and limited, smothering the film with long stretches of visual monotony that quietly erodes investment. Every action beat, disregarding the circumstantial stakes, boils down to one group of the characters struggling to reunite with the remainder after a separation. Slick sequences of choreography bring fresh bursts of dynamism here and there, standing out from the reserved, conversation-centric scenes that make up most of the runtime. Throughout its first half, it’s hard to fully shake the sense that the film isn’t holding its best cards, steadily setting the table before finally sailing into more fantastical territory past the midpoint. Outside of the Kosuke/Natsume duo, which quickly falls into a rhythm of arguments and reconciliations, the character focus on the rest of the cast isn’t as consistent or substantial. And during the climax, a few payoffs for these supporting players land like decent first drafts of polished ideas. If Drifting Home being perfectly fine is at all a disappointment, that only stems from the wish that it would have cohered a bit more resoundingly.

Drifting Home isn’t without its more unique touches, however. Certain choices, like a few horror-inspired sequences or some jazzy adagios weave in a more mature texture. The threat of death is real, and when the children do get hurt, there can be a little blood. These choices reflect the film’s representation of a transitional stage in childhood: from elementary school to middle school, on the cusp of teenage agency and a harsher reality. Their emotional maturity, particularly Kosuke’s and Natsume’s, is tested, as they are soon to enter a new chapter where responsibility for who they become in the world is placed more squarely on their shoulders. As a coming-of-age story, the film balances its juvenile schtick with a tenderness and allusion to the metaphysical that, while not necessarily thought-provoking, charmingly develops the film’s sensibility. It might not result in an anime destined to endure, but it’s enough to make Drifting Home a pleasant afternoon watch for genre fans.

You can currently catch Hiroyasu Ishida’s Drifting Home in theaters or stream it on Netflix beginning on September 16.

Comments are closed.