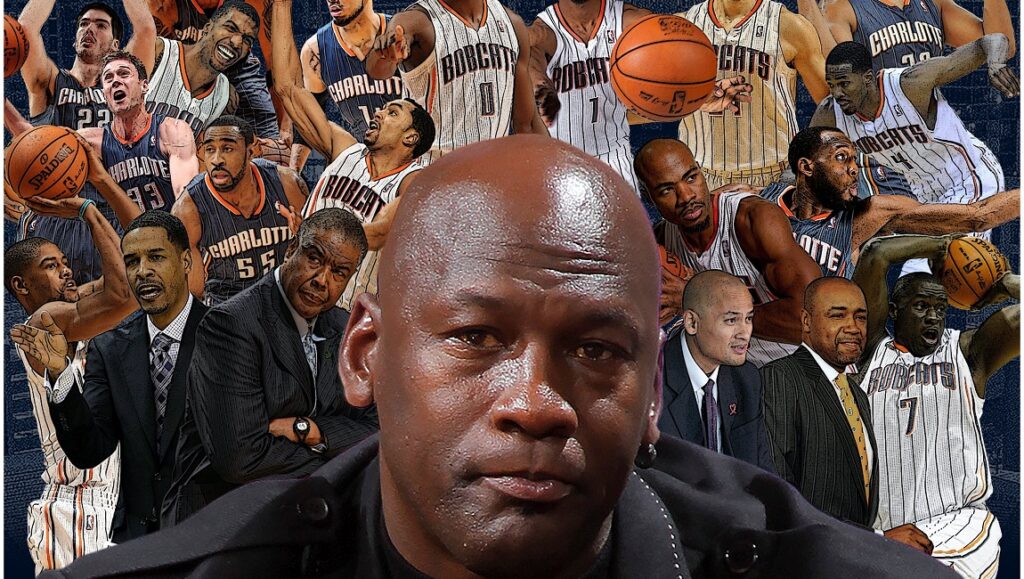

Basketball isn’t like other sports. Certainly not any that Jon Bois and co-writer Alex Rubenstein have covered before, which may go a ways in explaining why they brought in Kofie Yeboah and Seth Rosenthal as additional writers with their latest film. Unlike baseball and American football, basketball is hugely individualistic — even as it remains a team sport — where a single great player can totally define a team and propel them all the way to the top. The People You’re Paying to Be in Shorts is, in execution, something like a conversation with Michael Jordan, a player who did more than just define his team — he defined the whole sport. But at the start of the 2011-2012 season that this film follows, he’s 48 and has become an owner, the only other individual in the basketball world with as much power as he once had. His team, the Charlotte Bobcats, are quickly heading toward delivering the worst season in NBA history, and in a game with so many scoring opportunities, there isn’t much to hide behind. Such large numbers tend to flatten any randomness and chance; it’s difficult for the best teams to do anything but win and the worst teams to do anything but lose.

Despite building his films out of graphs and charts, chance is one of Bois’ biggest themes — he has always understood the limits of statistics. Captain Ahab: The Story of Dave Stieb (2022) is about a player who misses greatness mostly by definition, because the categories used to measure it are limited, to an extent even arbitrary. And so Shorts stands in contrast — in a way it’s the opposite of Section 1, released earlier this year. Rather than a story where choices and accidents weave together to create a miracle — a plane crashing into a stadium six minutes after the end of a game without killing anyone — it’s one of slow and inevitable disaster. The only randomness here spawns from the whims of powerful capitalist owners. After buying the Charlotte Hornets, Robert Johnson re-named them after himself: the Bobcats. He also changed the team’s colors for equally shallow reasons.

Indeed, the role of capital is cemented in Shorts from the very beginning. The season begins with a five-month lockout, during which the players and coaches aren’t even allowed to speak to one another, resulting in the eventual games all being crammed into a shorter timespan. Both of these factors would have a disproportionate effect on a team like the Bobcats that is still establishing itself, yet they were also brought on by the team’s very owner. Jordan was amongst those fighting to change the pay distribution between players and owners; the freeze eventually ended when the players’ split is taken down from 57% to 51.5%. Capitalism is, of course, deeply intertwined with individualism, and so the logic bleeds through: this is how Jordan, who more than anyone else gave the players such value, and who argued it was them who made the owners rich in his Hall of Fame speech a few years before, could double-back on his rhetoric in service of his own self-interest. Between Jordan and Robert Johnson, who was the first Black billionaire, there’s a clear and fascinating potential narrative about the ways that capitalism integrates those it once rejected, how you’re allowed to rise above exploitation (to some extent) as long as you agree to become the exploiter — which even takes on a psychological angle when Jordan says he’s looking for a player just like him — but that isn’t much explored here.

But all Jordan’s fame and power don’t seem to do much for his team. The Bobcats store is swamped when the new Air Jordans are released there. The crowd is promised free Bobcats tickets if they calm down, but they don’t want them. The team only reaches national television when that worst season of all time starts to become a real possibility. It’s simply embarrassment after embarrassment. Sports can be a great equalizer: if Section 1 showed us how everything could go right against all odds, Shorts makes a study of how they can all go wrong, and both are comforting in their own ways. Even if Jordan built (some of) his wealth in front of our eyes by doing something most can agree is exceptional and of value, it’s still cathartic to see the rich and powerful sweat. And so, all that’s left for the Bobcats to achieve is to avoid registering the worst all-time season in NBA history, while still doing just bad enough to land the best odds in the draft lottery, a little light in their darkness. A generational talent would at least mean that the next season isn’t the wash that this one has long become, and that talent is waiting in the wings in the form of Anthony Davis, bearing Jordan’s own number 23. It all has the whiff of destiny — this is who Jordan has been looking for, that someone just like him.

For a moment, Bois wonders if Jordan could have tanked on purpose in order to get a better shot at Davis, but that seems to be falling for the myth, the idea that a man who was great is a great man across the board. As tempting as that logic may be regarding someone who was so undeniably great in one arena, it seems extremely unlikely, Bois argues, that Jordan would have willingly taken it this far: it would require him to accept fielding the worst team of all time, and being booed at his own stadium for what must be the first time in his life. Rather, it’s that he is truly failing that makes Jordan a tragic figure, one to who Bois is quite deeply sympathetic. The crowd at his Hall of Fame speech laughed when he said that he’d be playing at 50; they assumed he was joking, but he wasn’t and he told them to stop. He said he never expected to grow old, but during this tumultuous season, he turned 49. His total consumption with the idea of getting on the court again has to be projected onto his players, he’s admitted as much, making his sublimation of them psychological as well as economic.

The final lines reach out to Jordan across the ironic setup of a conversation between him and Bois, wherein the latter states that he hopes the superstar doesn’t feel like he has anything to prove and asks him if he really thinks we’ll ever forget what he achieved. After all, this season is already a historical oddity that had to be dug out just ten years later. Still, Bois can’t help but wonder, if Jordan had known that Kwame Brown would have all but guaranteed the Bobcats didn’t fall to these depths, would he have paid him the 7 million he asked for at the beginning of the season? That tension between respect and suspicion makes the draft lottery such a rich sequence: when their fate is truly left to chance, it’s not clear what we or Bois really want to happen. Seeing the reaction of general manager Rich Cho slowed brings those conflicts to the surface, his feelings seemingly changing as we watch each pixelated frame pass one after the other, viewers left only to read his expression until it’s all too obvious that they didn’t get the first pick. It’s one of Bois’ most effective but oblique images, settling somewhere between tragedy and farce without ever becoming either (or both).

Still, it’s tough not to think that Bois gives Jordan too much credit throughout this portrait. He attributes to him this vision of long-term creation that doesn’t seem so different from the justification most capitalists embrace, one that allows for so much creative destruction. He might have shut down his own charity organization when it became too bureaucratic to actually help anyone, but he also let Nike produce his sneakers in overseas factories with low wages and often cruel working conditions. He might have stood by his team, even after so many failures, but he also made sure it would financially benefit him more than them. The personal does not negate the political. Jordan might be the greatest of all time, but in many ways, as Bois says of the Bobcats, he “just sucked in the regular way most things do.”

You can currently stream Jon Bois’ The People You’re Paying to Be in Shorts on Youtube.

Comments are closed.