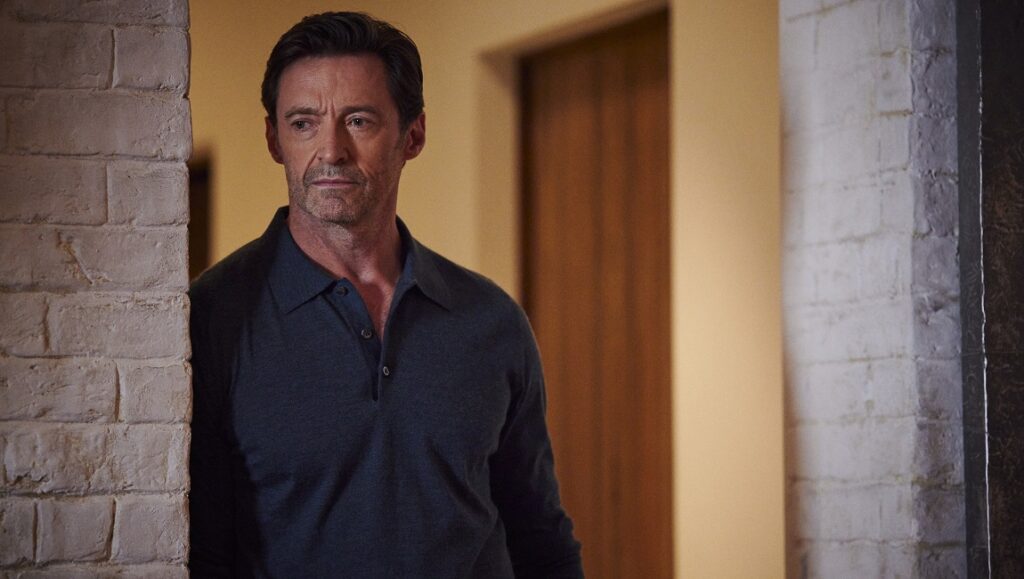

Film trailers sometimes embellish the truth, and other times overturn it entirely; Sony Pictures Classics’ preview of The Son, however, proves remarkably faithful to the film’s thematic and artistic vision. The two-minute montage opens with a bleary-eyed and desaturated panorama of the New York skyline, an image containing multitudes — the urban and corporate 21st century, set against the microcosmic themes of personal and social melodrama — and crystallizing through its hi-res clarity a carefully molded narrative of dysfunction and personal discovery to come. We then see Beth (Vanessa Kirby), maternal signifier, caressing an idle baby and humming to herself; a separate shot establishes the nuclear family through Peter’s (Hugh Jackman) suit-clad figure and smiling visage, framed by a door. He’s between two worlds in more than one way, as the film will show, balancing family with work, his marriage to Beth with the remains of one with Kate (Laura Dern), and his past regrets with his present responsibilities. All this in eight seconds, and followed by a title card of lean, minimalist typeface overlaid with “brooding string music” (so surmised by the video’s subtitle track); there’s a certain beatification in this apparent honesty, of a series of portraits stripped down to their bare essentials. One wonders, then, if The Son will lean progressively toward unhinged territory, as has been the case of late with films whose trailers deceptively employ the most banal of set-ups, or whether it will stick, instead, to its soppy, mechanically maudlin guns.

As it turns out, Florian Zeller’s second feature exemplifies a sad case of the latter, its dated and laughable histrionics coupled with a fourth-grader’s class presentation on familial dysfunction to fashion a rote, repeatable, and utterly predictable exhibit for the annual awards hullabaloo. It’s also almost entirely forgettable, were it not for an overwhelmingly A-list presence — comprising Wolverine, Princess Margaret, Lynch muse, and Sir Anthony Hopkins himself — miraculously absent from all proceedings bar the commercial. The effects of Zeller’s prestige assembly are double, complementing star power with the symbolic veneer of theatricality, except that The Son squanders this theatricality (it’s an adaptation of Zeller’s 2018 stage play) just as quickly as it establishes it, tracing Brooklynite anxiety with all the dullness of cliché and none of the innovative apparatuses afforded the medium. Broadly speaking, this anxiety takes shape as follows: Peter’s newfound happiness with Beth and their infant son is disturbed when ex-wife Kate shows up on their doorstep, requesting that he attend to his other, now-teenage son Nicholas (Zen McGrath), who has skipped school indefinitely and seems to suffer from some overwhelming ennui toward living. But Peter also has to fulfill his social contract as a successful lawyer looking to meddle in D.C. politics — and with family time already a luxury, his rekindled relationship with Nicholas looks headed for rocky waters.

Perhaps some close reading is due: Much like The Father, Zeller’s feature debut (also adapted from one of his stage plays), The Son deposits its titular characterization into psychological territory: Hopkins, in the former, as an aging man struggling with dementia; McGrath, in the latter, wrestling with acute depression. Here, however, the characterization is possibly twofold: as the junior figure of Nicholas struggling to articulate his identity to a wider, stranger world, and as the figure of Peter, a father to Nicholas but also a son to his own. Much like Nicholas, Peter — as Zeller takes tremendous pains to inform us — suffers from the universal trauma of unmet expectations and unavailable father figures, and his current role as caregiver to his children from two families places him in good stead to inflict this trauma onto them. So far, so good. But nothing kills the mood as rapidly as a tacky flashback or two. The Son, ever so intermittently, evokes the blind, parodic nostalgia of late-night cable ads, transporting us to simpler times so that it may moralize against the complex affairs of today, including — God forbid — the possibility of being sad without definable reason. Nothing, in addition, drains the soul as whole-heartedly as a blank canvas resolute in its blankness. Editor Yorgos Lamprinos appears to have culled from the massive B-roll archives a leaden collage of Peter’s working environs, first of him taking urgent calls in his high-rise office, then of him brooding absent-mindedly in boardroom meetings; the laughably signpost-y dialogues about ESGs and KPIs provide backdrop, but not backbone, for Zeller’s economical but ultimately empty elucidation of contemporary, upper-middle-class urban life.

In a way, The Son finds a curious resemblance in Lynne Ramsay’s equally squalid We Need to Talk About Kevin, given how both films bank on their elusive, one-dimensional entreaty to empathy. Nicholas, a blank slate and palimpsest of teenage angst and unknowability, parallels Kevin’s (Ezra Miller) defiantly rational id with a high school melodrama’s querulous counterpoint against authority, teasing shades of Chalamet without the charisma. Of course, Zeller is far from Ramsay’s equal in terms of interest, or even shock value; there’s a genuine moment in which father and son spar — clearly designed to elicit tears and sympathy — which had this viewer in a laughing fit instead. Such is Zeller’s modus operandi here, a far cry from even The Father’s “ingenious simplicity of set design,” that not even Hopkins’ brief appearance as the cold origin for Peter’s midlife woes can quite redeem the two from caricature. Meanwhile, Kate and Beth serve as thin vestiges of emotional and sociological realism, although this role is swiftly bookended by the film’s insistence on sacralizing intergenerational discord through sexist typification: the unbearable nag and irresponsible homewrecker, respectively. Even though it soon becomes apparent that The Son isn’t about depression so much as it is about an attempt to come to terms with it, Zeller’s pseudo-formal approach — in framing and feeling alike — accords to the film a stilted and half-baked quality, one which pushes its most pathos-laden moments into the realm of pathetic sentimentality. A hunting gun is introduced midway, and it follows Chekhov’s maxim to the end.

Published as part of InRO Weekly — Volume 1, Issue 3.

Comments are closed.