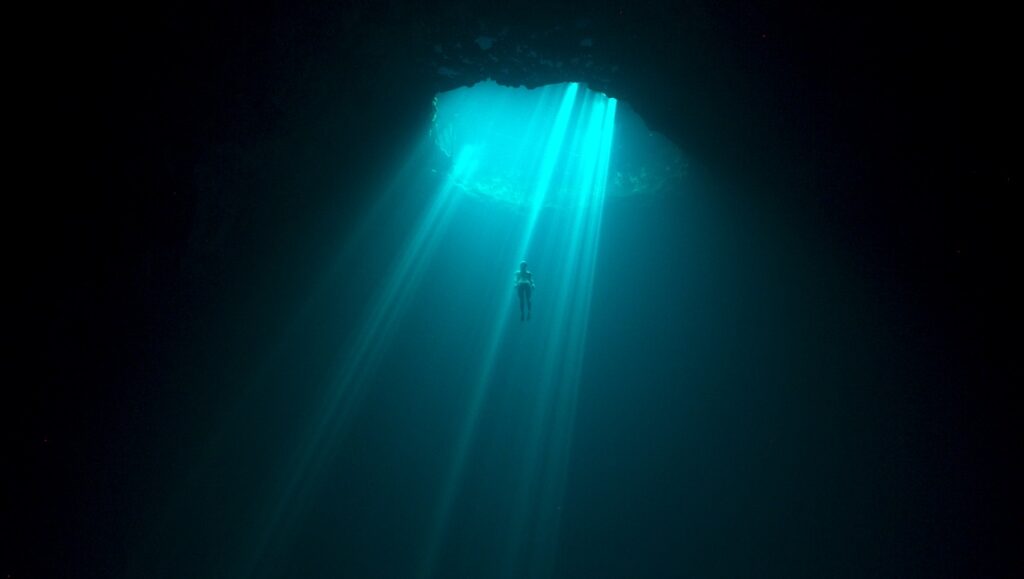

There’s no denying the sheer aesthetic appeal of Laura McGann’s The Deepest Breath. Charting the mind-boggling freediving efforts of Alessia Zecchini and Stephen Keenan, the documentary is a frequently ravishing exploration of the extreme sport in question — in which divers plunge to death-defying ocean depths without any breathing apparatuses, using only their exceptional lung capacity — capturing the deep down dark of the seas, and those who would be silhouettes against its vastness. For a while, McGann moves between Zecchini and Keenan’s respective narratives, kindred souls chasing something not quite articulable — notions of free living or recognition as the world’s best are bandied about, but never quite properly explored and accepted — and the early going is constructed of digressions and anecdotes of their respective lives, punctuated by awe-inducing images and acts that, in function, most closely recall the adrenaline-chasing timbre of Free Solo. Eventually, the two distinct threads coalesce into the film’s essential narrative, one that taps into the emotional core McGann carefully develops throughout, but which also highlights the film’s considerable weaknesses.

From a visual perspective, the primary obstacle is a problem of scale. Individual images of aquatic splendor certainly land with some sporadic power throughout, but capturing an individual disappearing into midnight darkness doesn’t hold the visual acuity of the image of someone willing themselves a speck against the grandeur of a massive rock formation in Free Solo; the ocean’s magnitude, meanwhile, remains mostly an intellectual exercise in The Deepest Breath. There’s no denying the power of what we see — the POV footage of dives lending a necessary, magnifying element to the film’s reconstructions — but it hits the ceiling of visual spectacle early and too often. This deficiency is supplemented via the film’s narrative construction: Zecchini’s storyline centers around her efforts to touch Natalia Molchanova’s freediving world record, while Keenan’s is more that of a wanderlust wunderkind who redirects his efforts to safety measures within the sport. There’s also a delicate love story between the two prominents that develops through this all, which indeed adds a bit of texture to the habitual documentation of deep-sea dives, although it doesn’t quite generate the emotional force a film of this character necessitates.

Still, the primary frustration present in The Deepest Breath is one of edifice. The narrative ultimately proves to be fairly straightforward, but as realized by McGann it’s massaged into a will-s/he-won’t-s/he docu-thriller, with the film’s language adopting a past-tense posture with both of the primary operatives’ storylines, essentially forcing viewers to engage with the text at the level of “who will survive?” From the beginning, we’re instructed to wonder which — if either, if both — storyline is set to endure after the end credits. In Free Solo, as a continued point of comparison, there’s a real-time appeal to the documentation, a quality that would have certainly redefined the final product under different circumstances, but which rings organic to the film’s documentation. Here, there’s a retrospective quality to the entire affair, one that leaves the narrative presented feeling somewhat manipulative, teetering on the line of good taste in its effort to mine drama from The Deepest Breath’s efforts at pulse-pumping spectacle. In Free Solo, there’s also the implied question of pathology, as the film consistently interrogates what motivates the man at its core. In McGann’s film, all such investigation is set aside, with the players’ explicit action prioritized as of more interest than their mystifying psychological motivation. Which means that, unlike the abyss that Zecchini and Keenan frequent, The Deepest Breath only flirts with a depth it should outright explore.

Originally published as part of InRO Weekly — Volume 1, Issue 28.

Comments are closed.