In the summer of 1969, thousands of music fans gathered for a once-in-a-lifetime show that would change the course of rock history. Bona fide legends delivered electric performances to critical acclaim. Then-unknown artists were catapulted to the spotlight overnight. A spontaneous all-star supergroup gave their first live show, ending the career of another band in the process. A biker gang provided security detail. A chicken met an untimely death. It was all captured on film, aside from one stubborn iconoclast who refused the camera’s eye. No, this wasn’t Woodstock. And it certainly wasn’t Altamont. It was the Toronto Rock and Roll Revival. And odds are, you’ve never even heard of it.

Directed by Ron Chapman, Revival69: The Concert that Rocked the World is an engrossing, enlightening, and even funny documentary shining a light on this forgotten moment in rock history. Similar in spirit to 2021’s fantastic Summer of Soul, which finally gave the Harlem Cultural Festival its due, Chapman’s film succeeds in bringing out the Toronto Revival from the shadow of Woodstock and sands of time.

Following a chronological timeline, Revival69 takes us through the story of how this historical event grew from its seed as a humble idea to the massive event it became, thanks to the work of a scrappy but dedicated (and well-connected) team. At its helm was 22-year-old newbie promoter John Brower. Fresh off the success of organizing Toronto’s first pop festival in 1969, Brower was hungry for more, and the idea for the Toronto Revival was born as a way to pay homage to the icons of the ‘50s who pioneered rock and roll. Brower’s team secured Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, and Bo Diddley for the festival, and booked Varsity Stadium as the venue. How it all came together couldn’t be more foreign to the way festivals are organized in the 21st century, an era dominated by corporate interests like AEG and Live Nation. “In the 60s, it wasn’t the music business, it was the music,” Shep Gordon, legendary manager of Alice Cooper, states in the film. That this show even happened is impressive in the first place, but it wouldn’t have mattered if the performances didn’t live up to the hype.

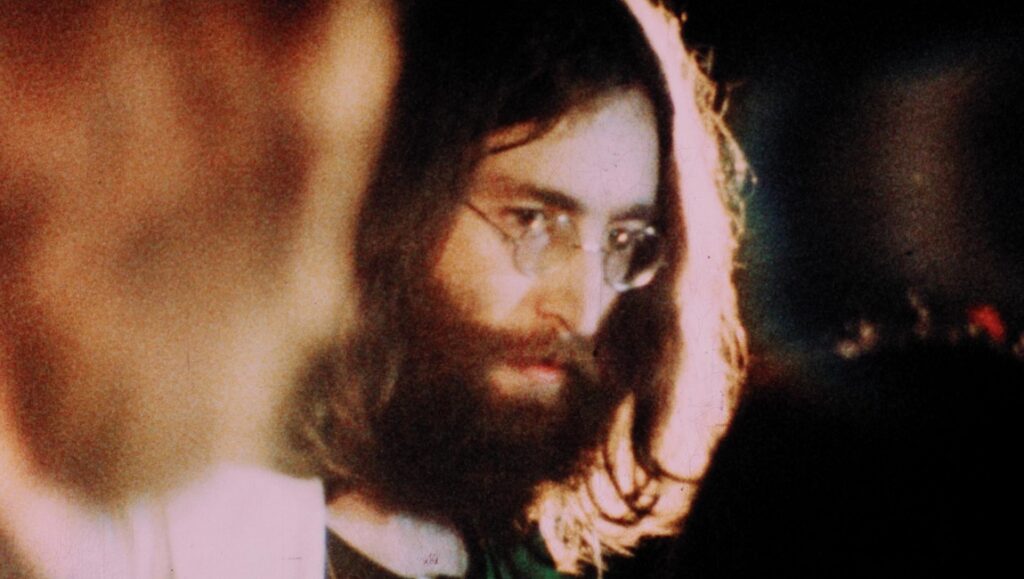

Revival69 is anchored in a tangible tension from the start. Specifically, can they pull this off? While core to the concert’s ethos, ‘50s rock and roll acts weren’t exactly in vogue at the time. In need of a contemporary act to attract a younger crowd, The Doors were named as headliners — costing organizers a pretty penny. Yet even this wasn’t enough to manufacture the hype needed to fill 20,000 seats. With ticket sales stuck at 2,000 just a week before the show, and with the event on the verge of cancellation, a true sensation needed to be booked. The answer: John Lennon. Thanks to a lucky connection at The Beatles’ Apple Corps HQ, organizers sold John and Yoko on the idea of honoring Lennon’s longtime hero Chuck Berry. Arriving at the peak of John and Yoko’s famous Bed-In for Peace, and also at a peak of his heroin abuse and depression, Lennon was excited about the idea of returning to the stage without the band that brought him to fame. He assembled a supergroup consisting of Yoko Ono, Eric Clapton, Klaus Voormann (bassist, artist, and friend of The Beatles), and future Yes drummer Alan White. This would be the debut of The Plastic Ono Band, mark a new chapter in the lives of John and Yoko, and hopefully prove to Lennon that a career was possible for him outside The Beatles. Seeming almost too good to be true, the press didn’t believe it would happen, and even the morning of, Lennon told organizers he wouldn’t play, before being pushed back into it by Eric Clapton. As it was, the gamble paid off.

And it pays off for the film, as well. Given the mystery surrounding the festival, most viewers won’t know if or to what extent it will all work out in the end, and observing how it all came together is a thrilling part of the ride. Fittingly, then, where the film truly shines is in the festival footage Chapman has assembled. Much like Summer of Soul, it’s thrilling to be able to see these stage icons in living color. Shot by a team led by the late, great D.A. Pennebaker, not only was the concert itself filmed, but we’re treated to incredible footage of its setup, backstage, crowd, and the surreal motorcycle caravan that escorted John and Yoko from the airport to the field (one of the film’s best sequences). This isn’t exactly a by-the-book concert documentary — we don’t get full performances from any artist — but it still manages to convey a palpable energy from each performance. The film is also chock full of endless amazing rock anecdotes: from the birth of Alice Cooper and his unhinged on-stage antics, to the undeniably weird yet forward-thinking avant-garde of Yoko Ono, to the crowd raising a sea of lighters to welcome Lennon to the stage (now a time honored practice at every concert ever). Yet it’s Chuck Berry’s performance that proves to be the film’s standout sequence. Backed by a group of teen musicians he’d never played with before, Berry overflows with joy and charisma. And there’s something so pure and bygone about his performance that it’s simply a marvel to see on screen.

The wealth of talent interviewed for the film offer great insight into the significance of the day — as well as lend it more humor than expected. Two particular highlights are Edjo Leslie, a rough-riding heartwarming Santa Claus and founder of the Vagabonds Motorcycle Club who provided security detail and funds for the show, and Rush’s Geddy Lee, who was in attendance that day and apparently tripping balls. The only two living artists not featured are Yoko Ono (who declined to appear) and Eric Clapton (who never responded to the filmmakers’ requests). Both polarizing figures, Clapton’s presence isn’t particularly missed, yet Ono’s would have added an extra dimension to the story given her complicated legacy, love story with Lennon, and unapologetic boldness she demonstrated on stage in Toronto.

Over the 50 years since the decade that transformed culture as we now know it, many moments have been recognized as the symbolic end of the idealistic ‘60s — from the police riots at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago to the murders of MLK and RFK to the disastrous Altamont Speedway Free Festival. Even more have been given for the end of The Beatles. The Toronto Revival invigorated Lennon with the confidence he needed to leave the group, sparking music’s greatest divorce. Given the incredible legacies swirling in Toronto during that summer of ‘69, Revival is a welcome addition to the history books and concert doc canon (and yet further required viewing for Beatles fanatics who need no convincing). Brimming with both revelry and reverence, Revival69 remembers a time when anything felt possible and arrives at a moment when we could all use a little bit of the optimism that felt so potent back then and so foreign to us now. It’s a welcome trip down a memory-holed alley of memory lane.

DIRECTOR: Ron Chapman; DISTRIBUTOR: Greenwich Entertainment; IN THEATERS/STREAMING: June 28; RUNTIME: 1 hr. 20 min.

Originally published as part of InRO Weekly — Volume 1, Issue 11.

Comments are closed.