The staff of In Review Online have come to the collective decision to abide by the international call from Strike Germany. We will be withholding coverage of the Berlin International Film Festival on the grounds that its institutional backing from the German government is marred by the latter’s censorship and marginalization of activist voices. Germany’s military and financial support of Israel, alongside the repression of those speaking up against Israel’s genocidal actions against the Palestinian people of Gaza and its assault and expropriation of those within the Occupied West Bank, should not be ignored or condoned. We wish to send our commitment of solidarity to all filmmakers and cultural workers who have joined this strike; business as usual is unacceptable. As over 100 Palestinians are killed each day in Gaza, we find the festival’s attempt to mitigate these criticisms with the gesture of The TinyHouse Project to be a condescension toward active and ongoing genocide. The festival’s poor attempt at good faith gives little actual space to the voices who push against empire, and offers only a tiny house, filled with hot air, off to the side, where no one else can see or hear you. While we will not be covering the Berlin Film Festival, that will not be the end of our participation in the strike. Instead, as a form of counter-programming, we will be reviewing selected works within the Palestinian Film Archive and publishing original writings related to these films. We declare solidarity with all participating in this strike, and solidarity with those participating in protests across the festival grounds.

In the opening moments of Here and Elsewhere, long-time collaborators Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville inform the audience that the images we are about to see are not the film they had originally intended to make. The original film was named Victory and included a third collaborator: Jean-Pierre Gorin, a previous Godard collaborator who together created the Maoist film collective Dziga Vertov Group, responsible for a series of radical films (and composed of mostly leftist students) such as Wind from the East. Victory was initially funded by the Arab League in 1970 and was shot in the months between February and July; however, it was by no means the final product. Things changed drastically when many of the subjects of the film died during Black September: a war between the PLO (Palestinian Liberation Organization) and the Jordanian government. Years later, both Miéville and Godard ruminate on the footage they shot and how the reality of war casualties has altered, or amplified, the meanings of the images. The result of this was far from the piece of agitprop that was originally intended; instead, the film is an intricate exploration of the relationship between images and politics.

In the first few minutes of the film, Miéville declares that the land of Palestine will not be taken back by peaceful means because they have lost hope in being able to use non-violent methods for liberation: “We shall construct peace with the help of this gun.” A persevering statement that remains true to this day: most recently, in the Great March of Return protests in Gaza — a non-violent protest that saw Palestinians walk, unarmed, to the violent borders that encroach their land, only to be shot at by Israeli soldiers, leading to the deaths of over 150 Palestinians. It’s with events like these that people lose hope in the notions of peaceful protest, democracy, and a path to achieve self-determination. The film is a stark reminder of how the Palestinian revolution isn’t always the apolitical, ideology-free movement that some people want it to be; the PLO, who at one point were often seen as the representatives of the Palestinian people, have their roots in armed struggle with their second largest member: The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, a revolutionary socialist organization.

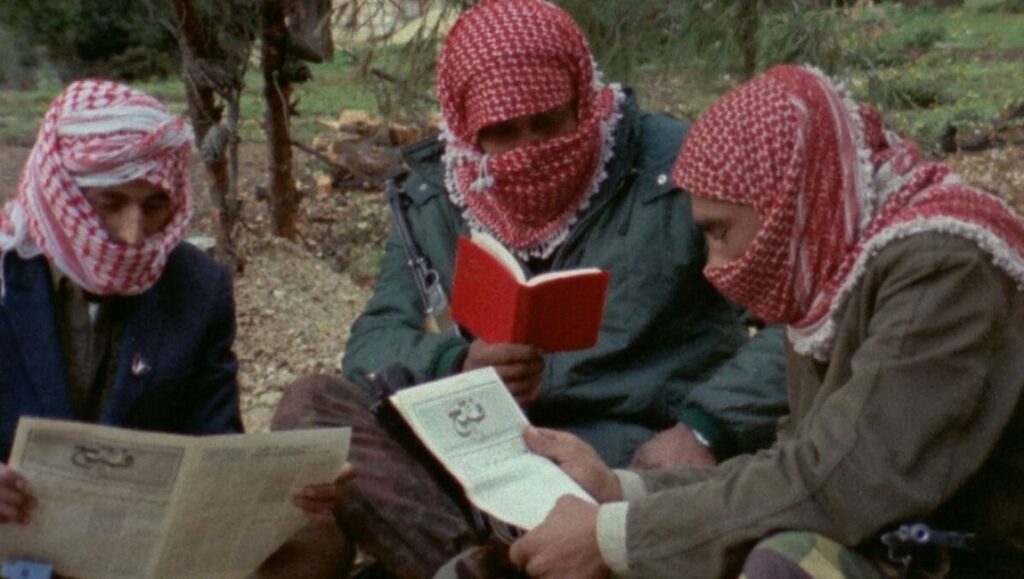

Here and Elsewhere is at its core a deconstruction of the process and final product of what Godard, Miéville, and Gorin filmed in 1970; together, they discuss the different elements of Palestinian life and liberation that they covered and how those individuals went about it: revolutionary forces read Mao’s Little Red Book and practiced using heavy artillery weapons. It’s through images like these that the film seems to evince Godard retroactively looking back at his own outwardly radical Maoist phase. Godard’s mournful tone hovers over the film as images of training Fedayeen collide with images of the bodies of their deceased comrades. Another juxtaposition is that of the French family, the film’s Here, sitting around the television playing against the images of Palestinians reciting poems amongst the rubble of destroyed homes: a composition that hasn’t ceased in its relevance, with the American population tuning in by the millions to watch the Super Bowl as Israeli forces bombard the city of Rafah. However, Godard and Mièville don’t use the family as a means to blindly attack how the mundane life of ordinary citizens contrasts to the horrors of fighting a colonial force; they instead use them to reflect on their own complacency: how much had changed in Palestine while they were editing the footage they shot, or how capturing these images failed to result in any actual change.

When people talk about Godard in negative terms, they often refer to his apparent pretentiousness, casting him as a sort of snob who believes himself above critique. Here and Elsewhere is a perfect counterargument to those critics, as it witnesses Godard at his most self-critical. The film is, in many ways, about the limitations of depicting revolutionary ideas through cinema or how even the mere act of attempting to capture the mechanisms of revolution through a camera is itself the act of spectatorship, detached as it is from the acts themselves. In an interview with Dick Cavett following the release of 1980’s Every Man for Himself, Godard says he believes that film to be his “second first film”: a rebirth of sorts that creates a new kind of cinema, breaking away from the Nouvelle Vague period. In many ways, Here and Elsewhere also feels like a transitionary film for Godard. His ’60s and early-’70s works are filled with radical formalist techniques, but they were also bitterly polemic about the state of modern society and how it shapes human relationships to both capital and each other. While this film is no less critical of modern capitalism and its inherent ties to colonial violence and imperialism, it is more abstract, and even less concerned about narrative and more about the image and its relationship to history.

One of the film’s most despairing moments comes when footage is shown of a group of Fedayeen who are discussing training tactics; one member says that the fact they are repeating the same routes will lead to them being discovered by the Israeli forces. Godard and Miéville discuss shooting that footage and the grave fact that three months after it was shot, every person in the frame would have been killed — they are actively discussing their own death. It’s a haunting reflection on the failings of armed struggle and revolution. But Here and Elsewhere isn’t solely about Palestine; Godard discusses, albeit in an abstract way, the ways in which images and sounds have failed other revolutionary movements: the Spanish Civil War, Pinochet’s U.S.-backed fascist coup in Chile, British imperialism over Ireland — a dialectical reading that links together a variety of historical events through the context of the current Palestinian resistance. Despite the fact that all of these events have shaped the history of left-wing praxis and theory, Godard’s voice is full of tangible gloom that feels somewhat defeated in how common the feeling of defeat is: including Godard’s personal attachment to the failed ’68 protests in France, the clips of which frequently cut into the film’s short runtime. These haunting ruminations of failed resistances to capitalistic power feel like a collection of lost futures: specters of a better world plaguing Godard. The key difference here is that Palestinian resistance persists, despite how much the Western world wants us to forget about it.

Godard and Miéville have both made a wide range of crucially important films investigating how images relate to the world’s rapidly changing political atmosphere, but none seem as important, and unwavering in relevance to modern-day politics, as Here and Elsewhere. It’s a film about many things: the sorrow of death during revolution, the impossibilities of peaceful change, and the docile acceptance of images by disconnected spectators. But despite the film’s melancholic tone, it never feels consumed by hopelessness or becomes a film about the misery of defeat. The two directors seem to reach out to a form of humanism that comes from the pure, unwavering representation of Palestinian resistance. In the film’s last moments, when discussing images of Palestinian resistance, Miéville asks: “Where did the inability to see or hear these very simple images come from?” It’s a statement that’s sadly as relevant in 2024 as it was in 1975, particularly as the Berlin Film Festival continues on as normal despite calls for a boycott. It’s a situation that immediately brings to mind Godard and Truffaut shutting down Cannes in 1968 in solidarity with the protests, and begs the question: where does our solidarity with Palestine start, and why does it end so quickly?

Comments are closed.