“I see so much, burns my eyes.”

– Godflesh, “Xnoybis” (1994)

“I can see, I can see, I’m going blind.”

– Korn, “Blind” (1994)

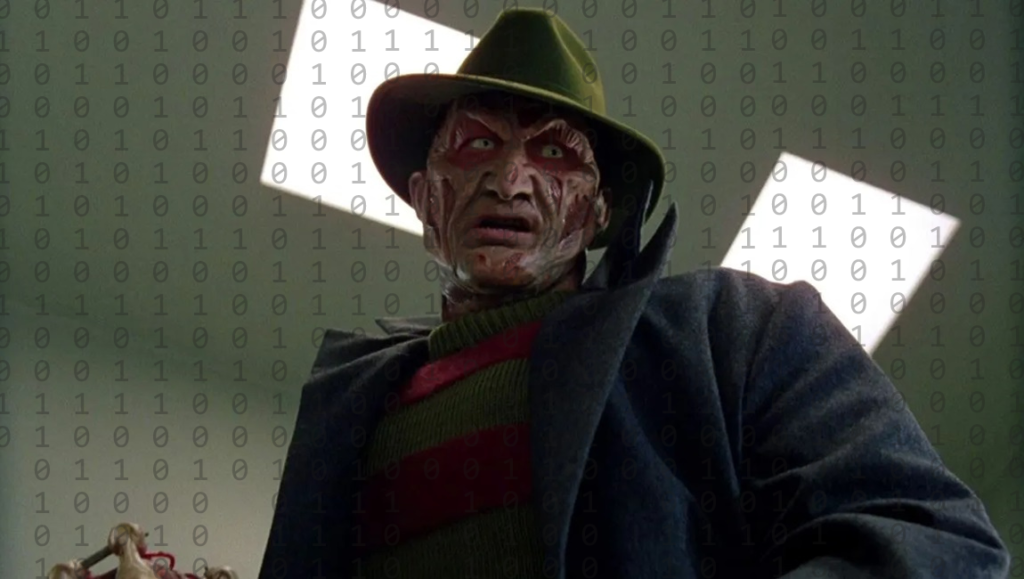

In New Nightmare, Wes Craven’s meta-sequel to A Nightmare on Elm Street, Heather Langenkamp — playing herself — balks at her toddler son’s enthusiasm for the gruesome Grimms’ fairytale “Hansel and Gretel.” The cathartic necessity and Jungian charge of fairytales are vital to the film: while Hansel and Gretel use a trail of breadcrumbs to trace their steps back home from the woods, New Nightmare’s child leaves a trail of sleeping pills for his mother so she can rescue him from Freddy Krueger’s Boschian dreamscape. It reimagines the Grimms’ breadcrumbs as portals from corporeal reality into the dark unconscious, and also anticipates the breadcrumbs of the Internet: web elements that chart and record visitors’ navigational journeys.

English computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee began dropping breadcrumbs toward the dark woods of the World Wide Web in 1989. He originally theorized the Web as a means of “universal access to a large universe of documents” that would combine three key components: hypertext, transmission control protocol, and a domain name system. His vision materialized in 1994, the “Year of the Web,” when websites began opening to the public. This development set the stage for the 21st century’s postmodern chaos — outsourced cognition leading to progress and disintegration in equal measures, facts and lies entangling in a collective frenzy of paranoia, rage, and disorientation.

Horror cinema has responded to the nascence of this seismic shift, confirming Stephen King’s claim in Danse Macabre that the genre has unique access to “terminals of fear […] so deeply buried and yet so vital that we may tap them like artesian wells — saying one thing out loud while we express something else in a whisper.” This certainly holds true for a constellation of horror films in 1994 that explore issues of eroding agency, permeable subjectivity, and externally authored reality.

Playing himself in New Nightmare, Wes Craven stands in an office whose bookshelf houses King’s Cujo beneath several social science texts. The combination of books looming over Craven-as-Craven’s writing space signals the film’s commitment to horror as a cerebrally substantive endeavor; indeed, this applies to former college professor Craven’s entire oeuvre, from his exploitation Ingmar Bergman remake The Last House on the Left to the incisive social commentary of The People Under the Stairs and beyond. New Nightmare plays like a definitive work within, a meta-commentary on narrative and agency that predates Scream by two years. Playing himself as a conduit for his own screenplay rather than its engine, Craven tells his protagonist and lead actor Heather, “I wish I could tell you where this script is going. I don’t know. Look, I dream a scene, I write it down the next morning. Your guess is as good as mine as to how it ends.”

The layers of compromised agency are thus twofold — Heather finds herself subject to the scary machinations of Craven’s screenplay, which is itself guided by some unconscious author. Craven locates his film’s imagery from a deeply subterranean source, describing Freddy as an ancient entity that has “taken different forms in different times.” He says this shapeshifting entity’s only consistent trait is its M.O. of “killing innocence.” Freddy is Craven’s archetypal manifestation of a much vaster social symbol, signaled by the finale’s invoking of “Hansel and Gretel” and the Christian symbolism of serpents, devils, and stones engraved with the names of the seven deadly sins.

The film also anticipates the machinations of the Internet to come, Freddy being the monstrous outcome of social recklessness (the original Nightmare film reveals he is a child murderer who was killed by vigilante parents after the legal system let him off on a technicality). Of course, Freddy fills the role of the Gothic revenant, the return of the repressed, but he also symbolizes a collectively concealed evil who takes power in the unconscious, attacking his victims in their dreams. 30 years later, Freddy anticipates tech corporations’ pernicious interests to keep their users “asleep” and dependent on unconscious persuasion. Craven adheres to the mythological necessity for catharsis, concluding with Heather reclaiming her own story and vanquishing Freddy; at least, until the release of Freddy vs. Jason nine years later.

Such catharsis does not occur in John Flynn’s Brainscan, something like the teenage metalhead counterpart to Brian De Palma’s voyeuristic Body Double. Like that film’s patsy protagonist, Brainscan’s 16-year-old lead Michael (Edward Furlong) mediates his fantasies through screens. He inhabits a veritable sanctuary of dark imagination: heavy metal and horror paraphernalia festoon his giallo-lit bedroom, a whip-wielding Alice Cooper fridge decal overseeing a gallery of movie posters, everything from I Was a Teenage Frankenstein to Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare. He places phone calls through a ghoulish proto-Alexa computer assistant named Igor, who responds with “Yes, master” to his verbal commands. Michael also secretly video records his neighbor Kimberly (Amy Hargreaves) through his bedroom window as she undresses — De Palma’s perverse specter looming large.

The membrane separating reality from fantasy begins dissembling when Michael boots up a mail-ordered CD-ROM game called Brainscan, marketed as “the ultimate experience in interactive terror.” Hosted by a pink-mohawked figure named Trickster — played by T. Ryder Smith like a cross between Freddy Krueger and Jim Carrey at his zaniest — the game customizes players’ narratives to suit their individual, unconscious selves. Depicted in slasher-style first-person POV, Michael’s first “mission” tasks him with breaking into a luxurious suburban home, murdering the sleeping owner with a kitchen knife, and returning home with the man’s severed foot.

Michael leaves the mission reeling with nervous ecstasy, until he sees his gurney-strapped victim on live TV news. The film incrementally shifts to an omniscient third-person perspective to accompany mounting ambiguity around subjectivity versus objectivity. As the game forces Michael to commit more horrific crimes, he becomes increasingly unsure whether he is experiencing simulation or reality. When he begins panicking, the Trickster mocks him by flippantly sneering, “Real, unreal: what’s the difference?” The film thus contests the contract between player and game, between character and plot, not unlike the externally authored horror story of New Nightmare. So too does it anticipate the impending darkness of online selfhood, with an isolated young man descending into intricate delusions, causing irreparable damage in his pursuit of affective escape.

Brainscan repeatedly toys with the uneasy correlation between libidinal drive and morbidity — Michael’s sex dream about Kimberly transforms into a nightmare starring the pallid zombie of his first victim. This thematic interplay reaches its climax when the protagonist battles the Trickster in Kimberly’s bedroom, the night-gowned young woman watching from bed as the Trickster’s face distends into an impossibly huge maw to swallow Michael whole. In a strange case of Jungian synchronicity, New Nightmare features an almost identical image, with hell-dwelling Freddy’s giant mouth surrounding Dylan’s upper body.

Contending with issues surrounding media and youth, Brainscan pokes fun at the contemporaneous moral hysteria of Satanic panic. Michael’s school principal embodies rumor-based conspiracies, equating horror films with cannabis, pornography, and rape in one logic-bounding statement. At the same time, though, the film’s narrative expresses unease at the braiding of sexual arousal with media violence, and at the wavering division between corporeal and virtual selfhood. Its wry, credits-interrupting twist ending bears grim implications: Michael’s sense of self-possession is an illusion, his life nothing more than a horror plot built from the nastiest dregs of his own unconscious. Again, the film reflects some of the concerns underlying Craven’s New Nightmare, where movie and reality intermesh and Heather catches her son watching A Nightmare on Elm Street in terrified awe.

Japanese filmmaker Gakuryū Ishii’s arthouse horror-noir Angel Dust ventures into territory akin to New Nightmare and Brainscan via forensic psychiatrist Dr. Setsuko Suma’s investigation of a serial murder case. Setsuko possesses the unique ability to “assimilate” her psyche with a suspect’s by studying the bodies of victims. This narrative conceit opens into the spooky terrain of intermeshing subjectivities and “thought possession.” Setsuko learns the serial killer’s first victim was involved in a cult called the Ultimate Truth Church, whose leader — the quasi-mystic psychiatrist Dr. Rei Aku — just so happens to be Setsuko’s ex-lover. The Ultimate Truth Church magnifies Angel Dust’s concerns with fraught agency and perception, built on painstaking techniques of “deprogramming” its members’ preexisting beliefs about religion and selfhood.

Angel Dust announces its unwavering preoccupation with psychic states and spaces with two key early images. First, Setsuko becomes lost in a cave’s black depths, and second, she emerges from a water-filled sensory deprivation chamber. These shots are vital not just because of their amniotic symbolism, though such metaphors warrant interpretation, but because they situate the narrative in the shadowed reservoirs of the unconscious. More specifically, the film traffics in explicitly Jungian symbolism (again, not unlike New Nightmare). As such, it is worth noting that C. G. Jung connects the unconscious to water and caves. In The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, he describes the former as “the commonest symbol for the unconscious” and the symbolic cave as “the darkness that lies behind consciousness.” Angel Dust thus uses Setsuko’s unconscious as a narrative lens, thereby signifying that its proceedings are bound up in the mucky terrain of subjectivity — a site compromised by trauma, dissociation, and Rei’s insidious “mind control.”

Like Brainscan, Angel Dust formally evokes its protagonist’s psychological landscape. Ishii peers into Setsuko’s psyche through hypnotic soundscapes, associative editing, and quietly surreal set design, with Setsuko and her partner’s apartment containing a lush greenhouse that hosts an oneirically ceremonial sex scene. Ritual masks hover all over Rei’s chilly mountain-view office, emblems of his shapeshifting manipulation. The film’s psychological grammar amplifies questions around Setsuko’s agency and cognitive reliability, depicting her head-hopping breakdowns through montages of audiovisual overload. By virtue of her psychic “assimilation” practice and cult-infected background, the film contests her very sense of self. In Angel Dust, the concept of “reality” proves as unstable as a serial killer’s twisted mind; the assumed divide between subjective interiority and external “objectivity” is in fact illusory… and breakable.

The themes undergirding New Nightmare, Brainscan, and Angel Dust also permeate John Carpenter’s In the Mouth of Madness, the third entry in his self-described “Apocalypse quartet” (preceded by The Thing and Prince of Darkness, and succeeded by Cigarette Burns). Whereas Ishii and Flynn explicate their ideas in expressly filmic terms, Carpenter hews closer to Craven’s literary sensibility by drawing from the well of New England horror fiction, especially H.P. Lovecraft’s cosmic pessimism.

The film follows a typically world-weary Carpenter protagonist — insurance investigator John Trent (Sam Neill) — in his search for the missing horror novelist Sutter Cane (Jürgen Prochnow). Hired by Cane’s New York publisher, Arcane, Trent uses the author’s writings to find clues and leads; accompanied by editor Lynda Styles (Julie Carmen), his investigation leads him to a New Hampshire town called Hobb’s End.

Hallucinatory images pepper their voyage, one nighttime vision revealing a bike-riding child cycling on an endless loop until he becomes a shrunken old man. This image carries innate implications of entrapment, evoking a hamster on a wheel and, by unconscious implication, a cage. It portends Trent’s own fate, with his belief in forward momentum revealed to be a ruse. The film ultimately upends its protagonist’s deluded sense of control by revealing Cane as the author of reality. Trent learns that Cane’s fiction has hypnotized readers into a state of madness and opened a portal for ancient, Lovecraftian Old Ones to reclaim the world. Trent scoffs that “God’s not supposed to be a hack horror writer,” but the film proves the opposite.

In the Mouth of Madness implies some innate, almost incognizable truth in Cane’s horror fiction (which visually, thematically, and geographically represents a New England Gothic tradition linking Poe, Lovecraft, Hawthorne, Jackson, and King). When Trent first encounters Cane’s fiction, he tries laughing it off as “pulp” nonsense about “slimy things in the dark” and “people going mad and turning into monsters.” Still, he confesses the stories achieve some inexpressibly powerful effect: “The funny thing is that they’re kind of better written than you’d expect,” he says. “They sort of get to you, in a way.” Here, Trent intuits his own marionette-like role in a fiction written by a Lovecraft-King amalgam, perhaps sensing the traits endemic to what Lovecraft would call a tale of “cosmic panic.” Cane has reached deep down his brainstem to scratch the places he feels but cannot see.

In his book-length essay Supernatural Horror in Literature, Lovecraft argues that in works of cosmic horror, a “certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces must be present; and there must be a hint, expressed with a seriousness and portentousness becoming its subject, of that most terrible conception of the human brain — a malign and natural suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space.” In the Mouth of Madness translates this literary effect meta-cinematically, concluding with escaped mental patient Trent wandering apocalyptically desolate streets into a cinema screening his own movie. As in Brainscan and New Nightmare, diegesis decays so the protagonist sees his own “character-ness” and recognizes his own non-agency. Like Brainscan’s ghoulish final gag, which sees a dog carrying a severed human foot, In the Mouth of Madness ends with a deranged moment of gallows humor: Trent rocks in his theater seat, popcorn in hand, laughing in hysterical horror at the mockery of his own existence.

Earlier in the film, Lynda tells him that “reality is just what we tell each other it is.” As if foreseeing the 21st-century online world in all its anti-science galvanizing, far-right conspiracy, and algorithmic brainwashing, she continues: “Sane and insane could easily switch places, if the insane were to become the majority. You would find yourself locked in a padded cell, wondering what happened to the world.” 30 years later, one cannot help but marvel at the cogency of her prophecy.

Comments are closed.