The Sparrow in the Chimney

Those who have seen the Zürcher twins’ other works, The Strange Little Cat and The Girl and the Spider, may have felt a tension building across the two titles. In both of those works, cramped living spaces lead to shoulder-bumping and repeated confrontations among the respective films’ families — where these near-silent prods fizzle into a sort of austere humor in Cat, a fuller passive-aggression boils in Spider. Communication in those worlds only makes things worse. And while one might expect a smaller stage to induce more drama, Spider offers two apartments to Cat’s single dwelling, giving its characters the time to themselves to brood and reflect and increase the tension. The Sparrow in the Chimney, their third in this domestic trilogy, is the inevitable explosion.

Here is also a tale of domestic warfare in the Zürchers’ most grandiose setting: an entire house, complete with land, a lake, and a faraway cabin. While details about the family’s history of spite and violence are teased as more guests arrive, Karen (Maren Eggert), something of a matriarch, does immediately reveal that all is not well in the house. She, along with her son Leon (Ilja Bultmann), fight openly as they prepare for the extended family to arrive for her husband Markus’ (Andreas Döhler) birthday party the following day. Leon is quite responsible for his young age, evinced by his cooking lunch for everyone, but the rare mistake is noted and criticized by the harsh Karen, whose sister, Jule (Britta Hammelstein), is quick to notice, serving Karen a disappointed glance. There’s also Jule’s husband, Jurek (Milian Zerzawy), their young daughter Edda (Luana Greco), and their new infant child that Karen stares at with a mixture of jealousy and disgust (or possibly something wildly different depending on one’s reaction to the Zürchers’ Kuleshov Effect). Then there’s Karen’s middle child Johanna (Lea Zoë Voss), born with a rare joint disease and a penchant for telling her mother that she hates her and wishes her dead; and there’s the last to arrive, the eldest daughter Christina (Paula Schindler), who had presumably run away to escape all this but has returned anyway. Finally, there’s Liv (Luise Heyer), who is not a part of the family but is a part of the drama.

This makes for quite the full house. At first, it’s difficult to keep up with each of the characters; Ramon Zürcher’s screenplay refuses to set up situations where every new character can explicitly announce their relationships with one another. Every conversation feels like a rehashing of an old fight or a continuation of a discussion that was shelved weeks ago. This builds a tense, mysterious atmosphere such that bizarre questions and insults — Why did Karen and Jule’s father kill himself? Why did Karen call Johanna “disabled?” — linger, only for the film to deliver an emotional barrage of revelations in the fiery third act.

Despite all these kinetic characters, cinematographer Alex Hasskerl keeps the camera still and focuses deep. By placing the camera toward a door or a hallway, this small cadre of emotional warriors can come, go, interrupt a conversation, or loom awkwardly in the background. Shallow focus is reserved only for intimate moments or emotional duels. This clever framing and blocking makes the house always feel busy, no matter how much peaceful golden-hour light refracts into the floorboards and onto the white walls and pale faces. And, though they may be busy, many members of this family are lost in their own heads as they obsess over the past or peer into a room to witness an affair. The strength of their pondering perhaps even brings new characters into existence: several times, Karen or Jule wistfully look into middle-distance, then a hard cut reveals new characters traveling, until another hard cut to the daydreaming sister cuts off that narrative. In normal film language, this would imply that the traveling characters are a flashback or that Karen is merely thinking about them; in this film, those characters then walk through the front door. It’s a jarring effect, and one that signals that the film will move beyond mere realism.

As the pieces of family history come together, The Sparrow in the Chimney slowly settles into Gothic storytelling. This house is the house Karen and Jule grew up in, and it’s haunted by a cycle of infidelity, death, and fire that played out once during the previous generation and is fated to play out again in this one. With each character either bickering or living in their own world, nobody pays attention to a dejected Leon whose unattended actions lead to one of the most casually disturbing scenes in recent film history. After that, the film abandons its static camera along with any semblance of realism. To portray the collapse of this domestic world, the Zürchers borrow the imagery and techniques of that other stress-fest about the chaos of hosting a home — 2017’s mother! — as well as that other film about the consequences of being a dick to your housemates — 2023’s Afire. Those final sequences cap a trilogy about animals, family, violence, and home life, but they go far beyond the polite drama expected from the naturalistic arthouse school. It’s hard to imagine a better ending to the Zürchers’ trilogy, as they’ve realized a credo that more commercial filmmakers have always known: subtlety is no match for an explosion. — ZACH LEWIS

Bogancloch

In the last 10 or 15 years, the micro-universe that we call the experimental film world has made a decisive shift toward a form of filmmaking that establishes observable, photographic facts as their aesthetic bedrock. As has often been the case with various strains of experimental media, we have no truly apposite label for this certain tendency. (This critic once rather clunkily called it a “non-rhetorical cinema of fact.”) Now, one might be more inclined toward something like “poetic nonfiction,” which has the advantage of descriptively dovetailing with the “creative nonfiction” movement in literature. Scott MacDonald has taken to simply calling these films “avant-docs.” Labels always occlude as much as they illuminate, alas.

More so than perhaps any artist outside the Harvard Sensory Ethnography Lab, Ben Rivers exemplifies this experimental approach to nonfiction filmmaking. His films have consistently taken some social or geographical fact (a landscape, a workplace, a person, an animal) and built outward from there. Rivers’ films insist that we cannot ever really understand something outside of a context. But he also makes sure that the context does not provide some prefabricated interpretation of the object under consideration. Rather, the subject and its context are mutually defining, like a figure in a landscape. He does not deal in concepts. He provokes mysteries.

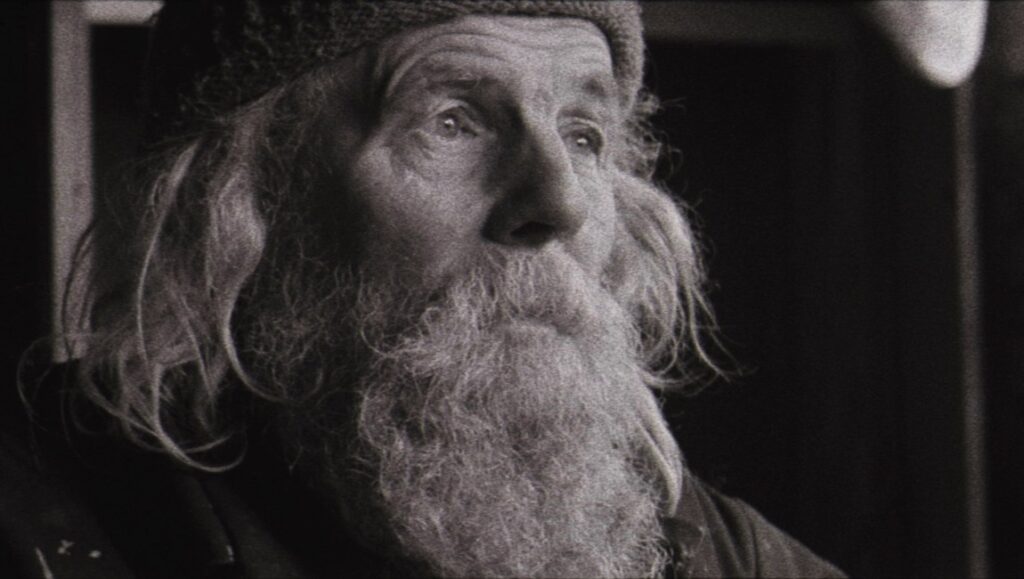

Rivers’ latest film, Bogancloch, is his third film (and second feature) focused on the life of Jake Williams, the defiantly off-the-grid Scotsman whose collection of odds and ends and jury-rigged devices for living were featured in 2011’s Two Years at Sea. Rivers and Williams have become friends over the years, and so the filmmaker has taken this opportunity to make a sequel of sorts to Two Years, checking in on Williams, examining what has changed in his life, and what has remained the same.

Why return to Jake Williams? I interviewed Rivers, and he mentioned an appreciation of the 7 Up films, and having been partly inspired by that kind of longitudinal endeavor. But make no mistake: Williams is such a fascinating and charismatic individual that no real justification is needed for turning the camera on him once again. Bogancloch is named for the location of Williams’ large compound in the woods, and the first thing that strikes any viewer who’s seen Two Years at Sea is that the old man seems no worse for wear. Yes, he is a bit balder, maybe moving a tad more slowly, but he is still remarkably active and engaged in all manner of physical effort. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it seems this kind of life is good for you.

Even if 12 years haven’t provoked obvious changes in Jake, Bogancloch is very different from Two Years in terms of Rivers’ points of focus. Like the first Williams film, 2006’s short This is My Land, Two Years spends a lot of time visually articulating Williams’ daily practices, his solitude, and the various ways in which the man not only survives but thrives in the elements. His is a life in tune with the seasons, where a day’s work is dictated by the requirements of the natural forces that surround him. Bogancloch, by contrast, is about Jake’s engagements with other people.

In other words, he lives alone, but he is not a hermit. Rivers shows a group of hikers who happen upon Williams’ land and spend some time in his company. The film’s centerpiece features Jake and the young men and women sitting around a campfire, singing a folk song called “The Battle Between Life and Death.” While its theme is applicable to all, of course, it takes on particular meaning with respect to Williams, who is indeed growing older but has no intention of going gentle. Bogancloch gives the immediate impression that it is possible to live outside of culture and history, making one’s own private path. But the closer we look, we learn that this is an illusion. Jake’s existence, timed to the rhythms of the forest, actually makes him more acutely aware of his place in the cosmic order. — MICHAEL SICINSKI

Sleep #2

Despite his increasing arthouse acclaim, Radu Jude has never been associated with a distinct stylistic stamp; indeed, he has long flitted between various formalist modes, so much so that the uninitiated might not realize that the same filmmaker made, say, The Happiest Girl in the World and Aferim!. His most popular films, Bad Luck Banging, or Loony Porn and the recent Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World, at least share an elastic approach to structure — the former a triptych, the later a diptych — as well as a fascination with engaging with extremely current events (namely, Covid and its immediate aftermath, political polarization, and the gig economy, amongst other hot-button subject matter). Interspersed between his features are a series of documentaries and experimental essay films, although projects like The Exit of the Trains and The Dead Nation have found limited distribution outside of the festival circuit.

Which is to say, one very much gets the sense that Jude is interested in so many different things, both politically and aesthetically, that he’s perfectly willing to churn out smaller-scaled, experimental efforts in between his more traditional, narrative-driven projects. And at the 2024 iteration of the Locarno Film Festival, he has dropped two new mid-length projects — Eight Postcards from Utopia and, under consideration here, Sleep #2. A title card lists only two credits: “A desktop film by Radu Jude,” followed by “Editing Cǎtǎlin Cristuțiu.” A second shot gives us a pertinent Warhol quote: “The most wonderful thing about living is to be dead.” From here, the brief, 60-minute film consists entirely of found footage compiled from the 24-hour video feed of Warhol’s grave site at St. John the Baptist Byzantine Catholic Cemetery in Bethel Park, PA. The material appears to have been arranged in a loose chronology, starting off in warmer, sunny weather and ending in winter, complete with delicate snowfall. Otherwise, the footage is a hodgepodge of various “events”; visitors come and go, some taking selfies or kneeling at the gravestone; a landscaper is seen cleaning up the area and applying fertilizer to some plants; and occasionally, the footage switches to a kind of low-fi night vision look. There are sunny days and rainy days, and sometimes the camera is zoomed closer or further away from the locus of the action. It’s all very splotchy, fully of digital artifacting and crushed, pixelated blocks of color.

Overall, this results in an appealing aesthetic, and one that links the film to a lineage of recent works including Joële Walinga’s Self-Portrait and Éléonore Weber’s There Will Be No More Night. Of course, dubbing the project a “desktop” film also evokes the work of Kevin B. Lee (who is thanked in the end credits here) and Chloé Galibert-Laîné, although their films typically forefront the human labor that goes into their making, an element missing in Sleep #2. And then there are the parallels between Jude’s project and Warhol’s; the title obviously suggests that Jude’s film is a sort of sequel to Warhol’s own 1964 opus Sleep, which documented via looped footage approximately 5 hours of John Giorno sleeping. indeed, duration was one of many ideas Warhol explored in his film work; besides Sleep, 1964’s Empire runs around 8 hours, while other assorted projects are shorter but still otherwise elongated (Blowjob lasts about half an hour at 16 frames per second; Eat is 45 minutes long). Then there are his numerous “screen test” films, which Jude surely had in mind as the parade of mourners pose and snap photos beside the late director’s tombstone. To keep the temporal in mind, and given Warhol’s justly famous maxim that “in the future everyone will be famous for 15 minutes,” one also wonders here if these visitors are hoping, consciously or not, to absorb some of Warhol’s celebrity via proximity or osmosis (or if the revelers are even fully aware that they are being recorded). And so, while Sleep #2 is a simple, even minor film, a sketch of an idea really, it’s one loaded with suggestion, potential significance, and room for intellectual play thanks to the long shadow cast by Warhol’s art ad legacy. — DANIEL GORMAN

Bang Bang

Despite three decades of reliable character actor work and idiosyncratic supporting roles, it’s surprising to find that Tim Blake Nelson has seldom been granted the chance to shine as a leading man. Sure, the Coen brothers gifted him the eponymous role in The Ballad of Buster Scruggs after years of collaboration, but Nelson has rarely had the opportunity to carry a feature film all on his own. Enter director Vincent Grashaw, previously behind What Josiah Saw, who, with his latest film, Bang Bang, hands Nelson a shot in/at the title. And that’s both figurative and literal here, as Nelson stars as Bernard “Bang Bang” Rozyski, a former boxing champ turned irascible layabout, now facing a new lease on life… — JAKE TROPILA [Read the full previously published review.]

Death Will Come

Death Will Come, German director Christoph Hochhäusler’s latest feature (and first French-language production), follows a contract killer, Tez (Sophie Veerbeck), who is hired by an aging crime lord, Mahr (Louis-Do de Lencquesaing), to find and dispatch the persons responsible for killing one of his couriers. Per the director’s own description, it’s probably his “purest genre work” — and this assessment stands to reason. Portentous title aside, it subverts neither the expected tone nor the basic plot mechanics of its crime thriller setup. We open with a mystery about who killed the courier, and why; and we end with the mystery resolved. But in another sense, a “pure” genre production in the manner of the American B-movies of the classic Hollywood era is simply not possible today: for the medium having built up a history in the decades since, a certain level of genre awareness is inescapable. For Hochhäusler, as for the Godard of Breathless (1960), the question is not whether to transform genre, but only how one might do so.

In Death Will Come, Hochhäusler’s main task is to heighten not just our awareness of the characters’ impending mortality, but also the way in which their acceptance of their mortality changes the genre calculus involved in parsing any given sequence. Much of the film plays out as a series of cryptic conversations in dimly lit rooms, where we are asked to sort out the motivations of the various characters, as well as their relations to each other. And as with most films of this sort, the central tension is one of knowledge: the difference between a crime lord such as Mahr and his inferiors is not a matter of physical power, but of his greater grasp of the total situation in which their actions are embedded. In Death Will Come, the “twist” is that the key piece of knowledge does not directly involve the machinations of the murder, but rather has to do with how various characters respond to the impending death of a key figure. The genre template we have been led to expect from many a crime film involves sorting out the goals of each involved party. The difference here is how a character’s response to, and complete acceptance of, death can (potentially) short-circuit the usual genre mechanics. The result is a plot that finally circles back in on itself like an ouroboros.

What Death Will Come offers us, then, is not a crime film or murder mystery, but a sort of Wellesian enigma — think Citizen Kane (1941) or, better, Mr. Arkadin (1955) — where the enduring fascination of the film lies in how the actions of its central characters cannot be reduced to any governing, goal-oriented situation. And what the film lacks in interest from moment to moment, it tries to make up for in a closing structural flourish that recalls Michel Deville’s little-seen Death in a French Garden (1985), where we realize that we have been watching something like an elaborately staged suicide all along. If the film does not quite live up to that comparison, though, it is because this final revelation does not appreciably reverberate back through the rest of the runtime. With The City Below (2010), Hochhäusler managed a structural coup of this sort, offering a final minute that radically reframes the rest of the film. With Death Will Come, he offers something a touch more staid: a movie that attempts to recast the fatalism of the crime genre, but falls short of being transformative. — LAWRENCE GARCIA

A Sister’s Tale

For a certain type of documentary, intimate access to one’s subject is a double-edged sword. Leila Amini’s debut film is a close look at her family, in particular her sister Nasreen. A mother of two, many years into an unsatisfying marriage, Nasreen finds herself wanting to return to the passion of her youth. She wants to be a professional singer. There are several complications in achieving this goal, but one stands out above all others: since Iran’s 1979 revolution, women have been forbidden to sing in public.

The filmmaker shows us the frustrations of Nasreen’s life, many of which are caused by Mohammad, her unsupportive husband. It’s not just that he doesn’t approve of Nasreen’s singing, although there is that. He goes to work early and stays late (that’s his story, at least), and shows very little tenderness or even warm regard for his wife. Although Nasreen loves her children, she cannot help feeling that she squandered her youth by capitulating to the expectations of those around her.

Leila Amini provides a sympathetic eye and ear for Nasreen’s troubles, but the film doesn’t offer much more than that. At times, Nasreen can seem petulant and self-absorbed, going so far as to lock the kids out of her bedroom and ignore them while she records a singing video for TikTok. Of course, Nasreen is entitled to the proverbial “room of one’s own,” but she often seems incapable of understanding just how typical her problems actually are. One expects that A Sisters’ Tale will provide broader insights, using Nasreen’s specific story to highlight the various restrictions and oppressions that all Iranian women face.

But because Leila is filming her sister, and is embroiled in the family crises she’s documenting, A Sisters’ Tale has trouble making that broader connection. The film actually reminds of Actress, Robert Greene’s 2014 profile of a middle-aged woman trying to realize her dream of performing. Indeed, there is something universal about Nasreen’s situation, since women are so typically expected to raise families and forgo their own aspirations. But this also means that Amini needs to find her own specific angle, and that is precisely what her film fails to do. Neither a feminist exemplar nor a family diary film, A Sisters’ Tale merely assumes our interest because it is made by someone who cares so deeply that she cannot imagine that others might not. — MICHAEL SICINSKI

Invention

About halfway into Courtney Stephens’ new film Invention, a lawyer (filmmaker James Kienitz Wilkins) tells our protagonist, Carey (Callie Hernandez, co-screenwriter with Stephens), that ideas are as powerful as the products we can turn them into. It’s a cynical line, perhaps, or maybe just realistic. But it’s also an obvious assessment of the state of the world, one particularly pronounced in the rarified air of Locarno, where the film recently enjoyed its world premiere. In such a place, abounding with films absolutely full of ideas but short of traditional commercial appeal, the question of the horrors our ideas can be turned into is at once gravely important and embarrassingly superfluous.

Stephens’ and Hernandez’s film, a nimble and form-breaking story based in part on the real life and death of Hernandez’s father, is a piece of art brimming with its own ideas: about the opportunities that fantasy provides the form of a fiction film, and what it can undo when unleashed in a person’s mind. Everything about Invention points toward the subterranean, particularly the influence on things above the surface by those underneath. Its simple narrative follows Carey in the wake of her father’s death, which has left her with the tattered remains of poorly managed business ventures and a patent for a mysterious electromagnetic healing device — the film’s titular invention — said to interact with the body’s natural electronic signals to rid it of ailments. What becomes more pressing than his mismanaged business practices, however, is the legacy of paranoia embodied not only in her father’s machine, but in the lack of clarity about who her father actually was. It’s up to Carey to piece together the mysterious story of her father’s life through encounters with old friends and business partners, all while the archive, long a preoccupation in Stephens’ practice and here presented in warmly distant clips of Carey’s father’s TV appearances, traces his winding path toward paranoia.

The notion of property, both private and exclusionary, as Carey’s lawyer notes, is the point from which all manner of paranoia germinates. She learns her father, Dr. J, was fiercely protective of his invention’s purity, unwilling to sell to venture capitalists eager to make a quick buck regardless of the machine’s effectiveness; and in passing the patent for his invention to his daughter, too, expressed distrust in others. The role of grief can be slotted into this framework as well, like when Carey misses out on an airline’s bereavement discount because her travel fell outside their official two-week bereavement window. When you don’t even have ownership over your own grief, the mind becomes porous, receptive to other fictions and fantasies that explain the previously unexplainable.

Invention is a kind of paranoid noir for the neo-mumblecore set, in which the anecdotal recollection of a dead man’s history unfolds before his clueless daughter, who’s already unsure how to navigate the world in numbing, unresolved grief. Like in post-war America in the late 1940s, the world’s paranoia is brought squarely to home, slowly winding its way into the psyche of our objective protagonist. A past associate of Carey’s father, Tony (Tony Torn), quotes Emerson to remind her that “of all the ways to lose a person, death is the kindest.” It’s an ironic turn in the film, knowing how much of her father Carey had lost to his paranoia without her even realizing it.

Like all great noirs, Invention is anchored by a colorful cast of supporting players, all of whom destabilize and muddy Carey’s understanding of her father. Along with Tony, we meet a woman (Lucy Kaminsky), an ardent follower of Dr. J’s ideas and already deep into her own paranoid spiral; Henri, a venture capitalist stoner and silent meditator never too sedated to not follow up on a deal; a man (uncredited in the pre-festival screener, but bearing a striking resemblance to filmmaker Joe Swanberg) who at one point was meant to manufacture Dr. J’s invention and tries to comfort her in her repressed grief with a prayer; and an elderly employee at Tony’s antique shop, an expert clock restorer who expounds spontaneously on the conspiratorial coincidence of obelisks in city-states like Washington D.C. and the Vatican. As the paranoid woman tells her late in the film, some people are like concrete — impenetrable against the real truth of the world. Faced with her own doubts, Carey herself slowly becomes porous, and risks slipping into the same spiral her father might have.

Invention is never content to settle on one form. Within both the primary story, shot on hazy 16mm film, and the archival clips, shot on video, it deliberately calls its own creation into question — hardly a novel strategy. The question of how much of this film is the real investigation by Hernandez herself to learn more about her father is answered by periodic breaks in the illusion of the film, such as the off-screen voice of Stephens “wrapping” the character of Tony, or correcting Kienitz Wilkins’ character when he mistakenly calls Carey “Ms. Hernandez” instead of the character’s last name, Fernandez. These illusion-breaking tactics, however, present the very mechanics of filmmaking as a strategy for disillusionment, as seeds of doubt about not only what goes on underneath the shiny surfaces of our mass entertainment, but indeed underneath the surface of nearly everything on earth, including ourselves. The real fear that Invention confronts is where exactly the exploitation of the world’s unknowability can be, and already has been, taken. — CHRIS CASSINGHAM

Comments are closed.