British filmmaker Ben Rivers is competing in the 2024 Locarno Film Festival with his newest film, Bogancloch. It is Rivers’ second feature about Jake Williams, a Scotsman who lives alone in the highland forest. Fiercely self-sufficient, Williams has spent decades creating his own private world, one characterized by ritualized labor, the rhythm of the seasons, and his own priorities regarding how to spend his time. In some respects, Williams is an avatar for Rivers’ own filmmaking. Shooting in 16mm, hand-processing his footage, and editing it himself, Rivers is one in a long line of experimental filmmakers who abjure the industrial model in favor of artisanal image and sound creation. Both Rivers and Williams are committed to existence on their own terms, sharing the results with all and sundry.

In anticipation of the film’s premiere, I spoke with Rivers on August 1, 2024.

PART ONE

Michael Sicinski: Bogancloch is your third film featuring Jake Williams, yes?

Ben Rivers: Yes, there’s This is My Land (2006) and then Two Years at Sea (2011), and now Bogancloch. My plan was to make this latest film in 2021, exactly a decade on. But then, of course, things happened with the world.

MS: So what prompted your decision to return to Williams for another feature?

BR: It started as a joke with Jake, him asking, “when are we going to make the next one?” That was quite soon after Two Years at Sea because he really enjoyed the film, and I think he also quite liked the modicum of fame that came with it. So when he asked, I said 10 years. As the 10-year point approached, I started thinking it was a worthwhile idea. Jake is somebody I have access to, to go back and see what changes, if any, have happened in his life. I couldn’t help but think about the old British TV show 7 Up (1964). It’s so great to be able to go back to people and see them change. Obviously with Jake I’ve stayed in touch, gone up to visit, and I knew that he really hadn’t changed that much. Even visibly.

MS: Yes, going back and looking at Two Years, it’s amazing that 13 years on, he’s still as active as he was in the first film.

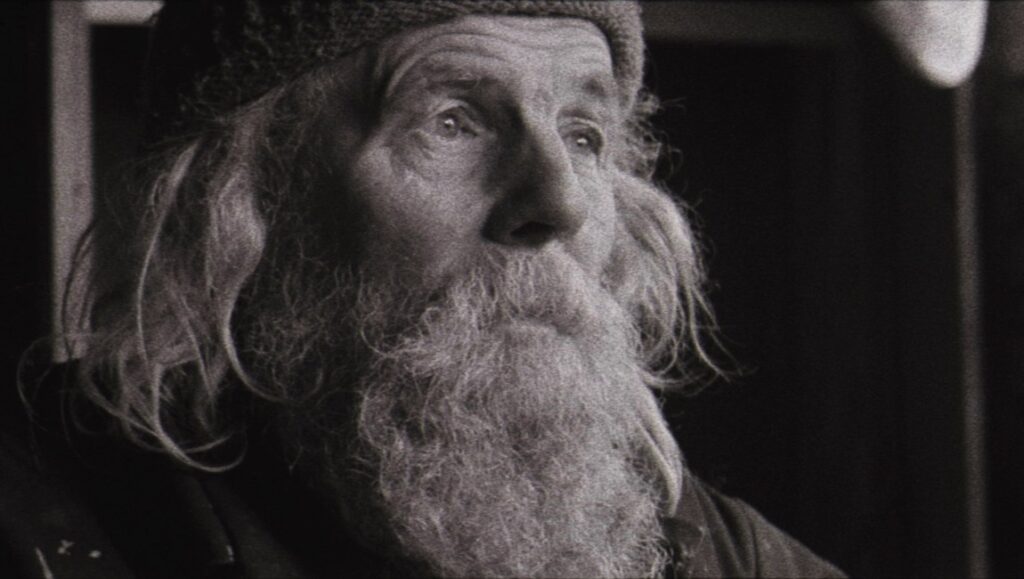

BR: Yes, he’s really in good shape, maybe a bit less hair on top, but an ample beard to make up for it. The more I thought about it, the more it made complete sense, filling out this body of work with Jake. It is a part of my overall practice, but also has its own special place. This is My Land was one of my earliest films, so I quite like this idea that working with Jake is this much longer-term project. So when I was making Bogancloch, I was already thinking about making another film in 10 years’ time. By then his body will probably have more noticeably changed. But maybe not. He is very fit.

But I do like this idea that I can also go back and make subtle changes in terms of what happens in the film. As I was leading up to making Bogancloch, I wondered whether I should try out different formal techniques, like different ratios, using color, or maybe changing the style completely. Then I decided no. I want the changes to be subtler than that. I stuck to the anamorphic black-and-white, and did make some smaller formal changes, like using color here and there. And also bringing in Jake’s voice, and bringing in other people. More gradual changes.

MS: Two Years at Sea is so much about him working alone, with various devices and rituals, showing how he lives. Bogancloch is a much more social film. Does this reflect something that has specifically changed in Jake’s life?

BR: I don’t know that his life has changed that much. He was a social person even then. But when I made Two Years at Sea, I was very clear that I wanted it to exaggerate the solitary side of his life. And part of the challenge for me was making a film that’s just focused on one person. No talking. That’s what it’s going to be. Whereas this film, having gone to visit him over the years, and knowing that he is actually rather social, makes that clear. Even though he’s chosen this way of life, he does encourage people to come around.

And since Two Years at Sea, there have been more visitors. The caravan in the tree was actually listed on AirBnB. It’s the cheapest place in the U.K., I think. And it’s still up there. It’s pretty sturdy, with the trees sort of hugging it quite well. People will come and stay there for a night or two. Jake really likes that interaction with strangers. So maybe he has subtly changed, becoming a bit more social. In Bogancloch, I wanted to reflect that side of his life. But not in too grand a way. In both scenes featuring other people, there’s a kind of dreaminess to them. There’s an uncertainty about their reality. I wanted that ambiguity. Is this something Jake is imagining?

But yes, I definitely wanted to bring other humans into the mix. Not just people coming to Jake’s place, but also him outside of his place.

MS: One of the most surprising sequences is when you see Jake in the classroom. In Two Years at Sea, you really get the sense that he is a solitary tinkerer, and he clearly has a lot of skills and know-how. But you don’t necessarily think about him imparting that wisdom in such a direct way.

BR: Yes, and actually when we made Two Years at Sea he was doing some by-teaching [substitute teaching]. He’d step into some local schools and teach science. But he’s never by the book, as you’d imagine, because he doesn’t live by the book. And he does want to impart that knowledge to kids. He wants to do it his way. I’d seen some of those experiments over the years. And I really liked his presentation of the celestial bodies around the earth, with a pub umbrella. It’s such a beautiful, rough demonstration.

As soon as I saw it, I knew I wanted the film to open with “the sun,” which is a tin can lid. And it grew from that. I got in touch with a local school. They were really helpful. The kids in the film were ones who were interested in drama. I like the looks on their faces. They’re listening, taking it in, taking it seriously, but they’re also a bit perplexed.

MS: Your citation of the Up films makes a lot of sense. Coming back to Jake periodically, these are (as anthropologists might say) synchronic films. We see how he was then, and how he is now. But the films don’t provide a lot of background or connective tissue. We don’t know how Jake became this person. Was that also a formal decision? Or did it have to do with what Jake was willing to reveal?

BR: Well, he’s never been that forthcoming around other people. Mainly, I think he’s someone who lives very much in the present. Or he’s thinking about next winter, or the winter after. And with both feature films, there’s a very deliberate decision to not really explain anything about him and why he’s there. Instead, I leave clues to the past around the film, the photos being one obvious way of doing that. Both films feature collections of photos I found, which I thought were very evocative of the past that we don’t really find out about.

But these are photos from India, from the Middle East, and in the final photo we see him as a young man. So the presumption is that he went on those travels. And that’s kind of enough for me, to know that he left Scotland, and he came back. Also, there are the tapes he plays, from those same trips. He would go to market and pick up those tapes, and he’s kept them all these years. And I just wanted to show him sitting there listening. For me, it’s enough to just show someone listening and remembering. We don’t need to be told what he’s remembering. I can leave it to other filmmakers to explain things.

In the years between the two films, there was a BBC Scotland TV program about Jake. It’s made by a guy who travels around meeting lots of people who live off the beaten track. [The program is “Ben Fogle: New Lives in the Wild,” S13E4, “Scotland.”] Since it was for the BBC, it obviously had a lot more interviews and more background.

MS: I kind of want to see it, but I also kind of don’t.

BR: Yes, it’s a bit cheesy, fixed on the idea that Jake must live such a lonely life. But if this journalist is traveling around talking to all these people, he must have the same thing to say about all of them, that they’re all lonely. I think there’s more to it than that.

MS: Sure. The BBC profiles these people but reassures their viewers that their way of life is the right one. We can’t all go off into the woods. The banks wouldn’t like that.

PART TWO

MS: As you know, the last 15 years or so has seen experimental documentary become a dominant mode. Most filmmaking that is tagged as experimental seems to have a realist, nonfiction element. Is that notion of “avant-doc” important to you as a filmmaker?

BR: Not really. It’s good to have a community, and a group of filmmakers with whom to be shown. It helps with the dissemination of the work. But when it comes to making the films, those things just don’t come into my mind.

MS: I’ve just observed that there are a lot more films being made that share some of your formal and ethical premises. It’s hard to say exactly why.

BR: Yes, sometimes you have these shifts, and they happen quite gradually. For me, when I started making these films, I was trying to figure out what kind of filmmaker I was. In the early 2000s, I was going off with my Bolex, getting to know the camera as a tool. Then I’d come home, process the film by hand, look at the footage and think about how I wanted to change it, so it wasn’t just a representation of what was. And one of the ways of changing it is with sound. Those early experiments were all without people. Then I had a desire to start including other humans. People like to see humans, I think. [Laughs.]

So that’s when I started looking for somebody who I felt a spark with. I went off on various journeys, and I found Jake. But at no point did I think, “I’m making a documentary about Jake.” It was more about making a film featuring a human, surrounded by all the stuff they’ve accumulated. The human is a part of that stuff. But it’s not a documentary. I’m not trying to illustrate his world or make an accurate “document.” It’s something a bit more transformative.

MS: And the details accrue. We learn more about Jake just by watching and listening. When we’re inside his home, there’s a sense of clutter that implies a small space. Then you get the exterior shots, and see that Jake’s home is a large, expansive compound. But you don’t illustrate that from shot to shot. One has to think across the film to perceive that.

BR: Yes, it’s an ample space, and he’s had a lot of time to fill it.

MS: I wanted to ask about the final shot. It seems to very clearly position Jake in the world, in the universe. What prompted you to end the film in that manner?

BR: It is in part that, thinking about him as a human on the earth. Bogancloch begins with an image of the sun, or an approximation of the sun. The tin can lid. At some point you see a carpet in Jake’s house that has the solar system on it. In the classroom, he’s also talking about the movement of celestial bodies. I wanted to end the film in a similar way. It’s Jake’s life, but it’s also a part of something much larger.

But one of the useful things about film sound is, even though there’s a grand, cosmic aspect to that ending, I keep the sound on ground level, with Jake in the tub. You even hear Jake talking to the cat, and the cat responding. I think that combination stops it from being too grandiose.

MS: There’s a kind of finality to the shot. But it also seems to open onto any number of possibilities.

BR: About halfway into making Bogancloch I became very certain that I wanted to make another film with Jake, in a decade of so (unless something terrible happens to one of us). And this is a sequel of sorts, and sequels have that kind of opening-up. Who knows what’ll happen in 10 years’ time?

But even though it’s quite different, there is a parallel to the end of Two Years at Sea. It’s a seven-minute shot of Jake watching the fire as it dwindles down to the embers, with his face slowly disappearing into the grain of the film. And I felt there was something cosmic about that as well — disappearing into the blackness of space. So I think there’s a mirroring between those two endings. He is very relaxed, and a part of something much bigger.

MS: That’s also reflected in the communal song at the campfire. It’s an intimate moment, but one that is about grappling with the mysteries of existence.

BR: It was quite important to find the song sung by the choir around the fire. I worked with a Scottish singer-songwriter named Alasdair Roberts. Early in the shoot, I had this idea that I was going to have these people moving through the landscape singing songs. These were poems I found that Alasdair arranged into songs. I filmed these parts, and they are nice on their own, but they really didn’t fit in the film. I knew that not long after filming them. So I had the performers do it again, with them coming to Jake’s house, singing around the fire.

I asked Alasdair and some of the others for suggestions of old songs. And this song came up, “The Fighting of Life and Death,” which is structured like an argument. This was somehow the perfect song for them to sing around the campfire, in this somewhat dreamy episode. I shot it with just the fire in the middle, so I was really pushing the film. It was right on the edge of not picking them up. Unfortunately, one person was underexposed and couldn’t be seen at all.

I liked this argument between life and death. Obviously, 10 years have passed between Two Years at Sea and Bogacloch. Jake is older. That struggle is always there. Still, in the song, life wins. Whatever happens, life wins out, planting its seed in whatever remains. There’s something really hopeful about that. Especially in this world we’re living in, which is so deathly.

MS: I’m surprised to learn that the song is intended to be an argument. It’s so peaceful.

BR: You’re right, the song is a calm argument. I mean, life and death are ancient foes. They’ve been around a long time. They don’t need to scream at each other.

Comments are closed.