Underground

Kaori Oda’s Underground is a film built around the meanings of its title, but it’s also apparently built up to 83 minutes out of reused footage from an earlier and shorter Oda film called Gama, which ran for a mere 53 minutes. Fittingly for a film that is always building shapes and forms out of lights in the dark, Oda’s ideas of the underground range from the obvious caves and subway tunnels to cinema theaters and dark exhibition rooms showing non-narrative art. The choreographer and dancer Yoshigai Nao, who serves as a sort of model to tie the travels across Japan together, seems to be awoken from her rest by the subterranean sounds of the earth and proceeds to practically sleepwalk her way through an exploration of these spaces. When she’s above ground, the lighting is so bright that one scene of the film begins developing light leaks that flare in from the sides and provide a flicker effect.

Materiality and sensuality are major concerns of Oda’s, ranging from sequences that explicitly highlight that this work was shot on film via tape splices and superimpositions, to the sight of Nao performing stretches and caressing the undulations of the cave walls. She’s not terribly concerned with locational coherence, which puts Underground in interesting contrast with the most recent masterpiece of cave cinema in Michelangelo Frammartino’s Il Buco. We bounce around from the caves of Okinawa to locations scattered all over the rest of Japan, suggesting a country unified by its undercurrents. Complicating this unifying approach is the recurring use of a talking head, who provides backstory about the mass suicides in Okinawa’s caves that occurred at the end of the Pacific war before literally turning out the lights — we all wind up underground without illumination at the end of the day. Nao wanders around the background of one of his monologues as a dry joke, and the expansion of her part in the film seems to be what sets Underground apart from Gama, which reportedly gives the storyteller a greater part to play in a shorter time frame.

One of the things that makes Underground both interestingly accessible and a little unsatisfying is that it’s almost all technique, and of a fairly straightforward sort. There’s always going to be something a bit pleasurable about seeing mysterious shapes formed out of darkness and droning soundscapes to capture geological time, and it’s not too difficult to put this particular puzzle together even when it’s obscured. This accessibility also means that the overall sense is that of a technical showcase that had to be blown up from Gama’s one-hour running time to this film approaching the 90-minute convention. Where Il Buco calmly and carefully plotted itself out and went deeper into unknown territories and darkness, Underground feels like Oda going for breadth rather than depth. One suspects that in this case, the earlier and shorter trip to these caves would be a more productive one than the longer attempt at greater immersion. — ANDREW REICHEL

Concrete Resources

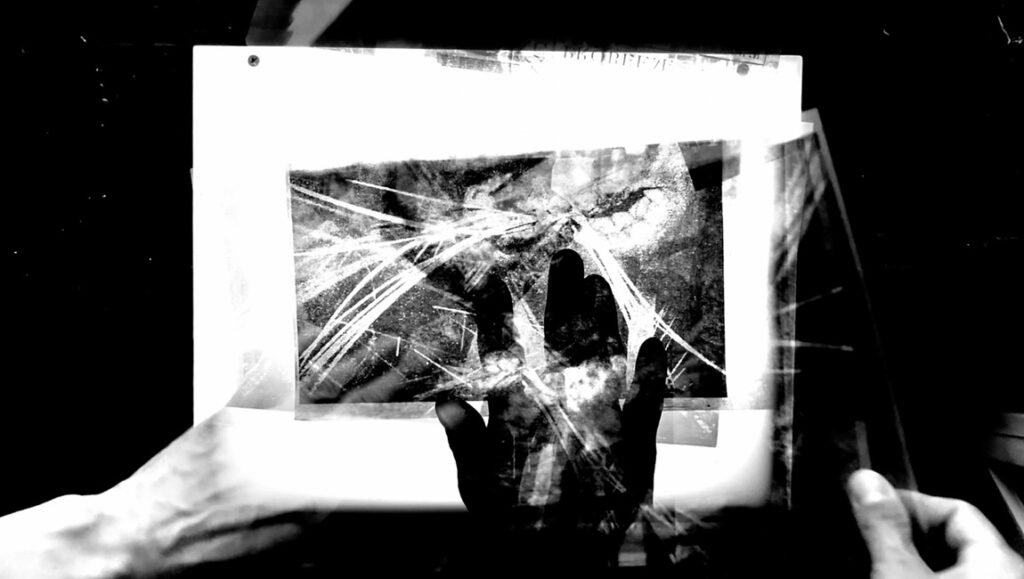

Emir West’s Concrete Resources (Thank you for keeping me a company of images) begins with a startlingly dense collaging of high-contrast, black-and-white images; the camera facing downwards as if manning an old-fashioned overhead projector. Hands arrange images on the flatbed surface while multiple exposures are overlaid, creating a flurry of hands and an overlapping of clipped photographic images that seem just on the precipice of coalescing into something stable or coherent. A calm voice recites text from Ernesto Cardenal’s La ciudad deshabitada, the poetic turns of phrase giving some kind of meaning to the largely abstract footage we are being shown. Gradually, little hints of color start to appear in the images, bits of greens and browns mixed in with the monochromatic palette. One can catch glimpses of faces, words, and landscapes, all just tantalizingly out of reach. It’s all vaguely reminiscent of Sara Cwynar (minus the color), or especially Peter Tscherkassky’s angular, jittery constructions.

But Concrete Resources gradually changes shape; the overhead view gives way to oscillating landscapes that become unstable and transform into bursts of white light. The white light begins to undulate, waves of shifting abstract forms that in turn give way to a shot of a road streaming by. The camera holds on the pavement to the point that it too turns into abstracted textures, a right, gritty patchwork of pure motion. One recited line suggests the animating force behind the film: “Thus by night, completely white, it emerges, in the middle of the land where its ruin has been built” West’s own description of the film adds very specific political context, that “through repeated interventions of war, resource extraction, and agricultural exploitation, U.S. and British powers have attempted to render Nicaragua a void along the Central American isthmus.” And, of course, Cardenal was a Nicaraguan poet and Roman Catholic priest who fought for social justice for decades until his death in 2020 at age 95. It all adds up to a filmmaker trying to make sense of a particular place, at turns pointedly materialist but also poetically so. It’s a film about searching for the words to describe a feeling, only to find that there are none. — DANIEL GORMAN

Contact Lens

One of the more welcome upsets in recent cinema history occurred in 2022, when Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles unseated Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo as the top choice on Sight and Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time list, a critic-polled survey conducted decennially. Generally, a male-dominated list — Citizen Kane held the top spot for five decades prior — the inclusion and placement of Akerman’s masterpiece was an unprecedented triumph and a welcome change of pace. In that regard, it makes perfect sense that Jeanne Dielman becomes a major supporting player in Contact Lens, the feature debut by Chinese filmmaker Lu Ruiqi. Purporting to “imagine the emancipation of women from the confines of narrow spaces and the tedium of routine lives,” Contact Lens wields the power of cinema as both tribute and successor to Jeanne Dielman, transcending what it means to see cinema as “escapism.”

Contact Lens centers around an unnamed protagonist (played by Yunxi Zhong), a young woman stifled by existence. She lives alone in a single-bedroom apartment, where the only real noise derives from the oppressive sounds of a microwave’s finishing beeps and the high-pitched whistle of a boiling tea kettle. To break free from the monotony of life, she escapes to the outside to fill in her notebook with images she sees and film strangers with a camcorder, even striking a friendship with another young woman who tattoos her body, determining the location based on dart toss. The other prominent feature in the protagonist’s life is a projector screen in her apartment, perpetually displaying what at first looks to be a shot-for-shot Chinese remake of Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman. As time dilates in the protagonist’s apartment, it’s evident that the Jeanne Dielman screen is not a regular film by any stretch of the imagination, but a gateway to another life.

Like Delphine Seyrig’s Dielman, Contact Lens’ protagonist is defined by repetition, waking up in the same room every day, burdened by the same routines, even going so far as to talk back to her microwave’s incessant beeping. Her true solace in the world comes from her contact lens, which are burned with the memories of images she’s seen, allowing her to relive favorite moments before they fade away. The protagonist is also frequently visited by a young girl and her unseen mother, presumably specters of her own childhood. Lu is depicting a woman in prison, meted out with fits of abstraction, and the real question mark belongs to the ever-present Jeanne Dielman screen. At first resembling a conventional motion picture, the in-universe protagonist of that film also finds herself trapped, such as when she approaches the camera to answer an off-screen doorbell and slams into the lens as if it were a giant glass wall. Further manipulation from the protagonist finds its way into the film, such as a disturbance of the projector screen warping the table in the faux Dielman’s kitchen. Contact Lens is ultimately an understanding these two women have of the other’s circumstances, and how they may be the key to each other’s freedom.

“Escapism” can have an ugly, negative connotation, largely referring to blockbuster, popcorn entertainment, the sort of film where one shuts their brain off and leaves their worries at the cinema’s door in order to partake in a studio-engineered rollercoaster ride. Lu’s film offers escapism of another color, asserting that life is the sum of its very ephemerality, and film offers true preservation in images, long after our memories have faded and our sight has failed us. Contact Lens feels like revelatory work, turning to cinema history to combat ennui and show us a path to making our lives a better place. — JAKE TROPILA

Assorted Prismatic Ground Shorts

Endings, directed by Isiah Medina and Phillip Hoffman, operates in two modes: as a diary-like collection of stills from rural life and as a flicker film. Hoffman’s ecstaticism and concern with the natural world in the film’s form are plain as day, though the specific rhythms of the piece appear to speak more to Medina’s contribution. The duo has a strong sense of montage: the pin-eye center of a bale of hay becomes the apparatus for the film’s bullseye windows of farm life. Movement is measured and operates according to natural geometries, shot beautifully across a range of stocks and colorways. The bizarre inclusion of a score in the back half of the film upsets these movements — fomenting discord where silence allowed a current.

Winter Portrait, directed by Fernando Saldivia Yanez, is a clear standout for its relative simplicity — an assured frame that acts as a window into the past and present of a Mapuche couple revisiting their wedding video. The pair occasionally makes commentary. The television they watch on is fixed into the top of the screen, a large sliding door facing out to the countryside behind it, with various artifacts of daily life occupying other nooks and crannies. The wedding video itself is a mixture of an incredible ethnographic document and a communal celebration. The wedding is performed in Mapudungun, an Indigenous language — something done so rarely that the video holds clips of interviews noting it. The video otherwise luxuriates in the pastoral: more time is spent among the cattle and greenery than with the happy couple in the selections the audience is shown, the husband and wife before the television, made even more compelling for their absence. Mireya takes a recording of the television on her phone. Emardo raises her hand, correcting her frame without prejudice, a tender redirection towards a brighter image.

A Message from Humboldt, directed by Matt Feldman, is a kind of rare treat in experimental film festivals of today — an artist doing something in their camera that provokes a genuine formal interest. Feldman has a great eye for the black and white he shoots, wandering through his bare apartment shortly after moving into it —” searching for hauntings and hidden meaning.” The opening of the film focuses on a candle, its place in a room’s geography standing opposite an open curtain to daylight: contrasting the sources of illumination. From this point, the film almost exclusively operates by spotlit selections — flowers, radiators, cupboards, doorknobs — the space is discovered in small details carried over each other in a hypnagogic display of multiple exposure photography. The film’s final section works as a mosaic, capturing dozens of vignettes in a 4×4 arrangement of tiled patterns of light. The film’s three acts in succession read as a spiritual ceremony: a candlelit attraction to the world beyond, a maze of questions answered in luminance, and a final masterwork grid that calls to one in the same way stained glass does when the sun’s brilliance is answered with a colored geometry.

Let’s Make Love and Listen to Death from Above, directed by Ayanna Dozier, is presented as a standalone work in her Super 8 trilogy, “It’s Just Business, Baby.” The film has two chapters: the first is a black-and-white accounting of the corporeal engaged in love. The shot opens in a corner of a street that pans to two bodies, at first shown as two pairs of legs winding up and across each other. Dozier’s camera is attracted to their feet, one perching, then torsos, lingering on the ways they grab each other. The revelation of their faces is more powerful for the amount of time the audience has spent imagining these strangers, who are finally realized as people with the appearance of their mouths, consuming every facet of the other’s face that can be held onto with their lips. The second chapter is in color, a simple walk down the street, much more reserved, with the two holding each other by the back pocket. The camera pans to reveal that this is the same street which was shown in the first chapter — the same stoop that held their passion passing by, ending a half block later with a kiss just as carnal as ever. Dozier’s use of pans to navigate space is as compelling as any film movement she’s ever made, as is her photography of bodies in the first chapter. The scenes in the context of each other suggest Dozier is interested in how color reacts to sex: in the dark. There is an apparent unconquerable and unknowable eroticism that penetrates every shadow, that the light reveals to be just another street corner. But then love is still found at the next. — JOSHUA PEINADO

Comments are closed.