Kontinental ’25

One would be hard-pressed to identify a film director on the world stage who has done a better job of articulating our historical moment than Radu Jude. His films over the last several years have offered a laser-sharp analysis of such contemporary ills as Internet shaming culture (2021’s Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn), the mobilization of national culture for reactionary ends (I Do Not Care If We Go Down in History as Barbarians, 2018), and the unfortunate continuities between Soviet-era authoritarianism and its newer, free-market equivalent (Uppercase Print, 2020). His 2023 film Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World may be his crowning achievement, as Jude manages to successfully juggle several strands of our current malaise into a single, wholly satisfying film. In it, Jude skewers the hustle culture of the gig economy, the toxicity of the so-called “manosphere,” as well as the seemingly limitless capacity of private capital to reduce human life to a series of economic externalities. If there is one single theme that unites Jude’s vision, it’s that the concentration of power in the hands of oligarchs and elites has not only accelerated human immiseration, but has naturalized itself to such a degree that any other way of life is becoming unimaginable.

Jude’s newest film continues the exploration of power and misery, but on a decidedly smaller scale. Kontinental ’25 could be considered a character study in benevolent narcissism. Whereas his recent films have been state-of-the-world reports of a broadly based sort, the new film narrows its focus considerably. Instead of looking at the systems that oppress us, Kontinental ’25 examines a particular type of liberal personality that allows authoritarianism to take root in everyday life. Deeply concerned but reflexively self-exculpatory, this kind of individual sleeps soundly even as they contribute to the callousness of the state, because they are ultimately convinced that they did the best they could.

The first part of Kontinental ‘25 follows a homeless man named Ion (Gabriel Spahiu) as he wanders through the Transylvanian city of Cluj, picking up cans and asking passers-by if they have any work for him and, if not, could they spare a couple of lei for his troubles. In one particularly striking tableau, Ion is seen walking through a park filled with cheap animatronic dinosaurs. As they snarl and swipe at the air, Ion quietly trudges through collecting garbage. Eventually we learn that he has been squatting in a boiler room in a building slated for demolition. Orsolya (Eszter Tompa), a Hungarian immigrant who works as a city bailiff, arrives with three masked gendarmes to evict Ion. She has gotten delays on the eviction to allow Ion more time to relocate, but the leeway hasn’t helped the situation. Finally they give him an hour to collect his things, but when they return, they find that he has hanged himself.

The rest of Kontinental ’25 focuses on Orsolya as she grapples with the aftermath of this event. Her boss jokingly compares her to Oskar Schindler as she relentlessly questions herself. Could she have done more? Orsolya is so distraught that she begs out of a family vacation to Greece, seeking counsel with an old friend, her mother, and finally her priest. But as the film unfolds, we begin to notice a performative air to Orsolya’s guilt. With almost scripted regularity, she tells the story of Ion’s suicide, often using the exact same turns of phrase to recount the tale. “I know it sounds odd, hanging himself from the radiator,” she repeats. Perhaps most revealingly, Orsolya always absolves herself just as she expresses her feelings of responsibility. “I feel like I’m to blame, but of course I am not to blame from a legal standpoint.”

Jude is providing remarkable insight into the liberal psyche. We know Orsolya is a “good person,” because she tried to help Ion. And because she is a good Christian. And because unlike her mother (Annamária Biluska), Orsolya detests the “fascist” Viktor Orbán and his oppressive government. Jude makes it clear that Orsolya is not a uniquely bad person. She is a fairly average individual with a charitable attitude towards others. But what Kontinental ’25 makes astonishingly clear is that when a person, any person, finds their sense of identity threatened, they will most likely do whatever they can to seal over the rupture. Although Jude makes it clear that an entire sociological apparatus is in place to make this possible, the penultimate scene suggests that religion has a very special role to play in maintaining a frictionless status quo. Orsolya’s priest (Șerban Pavlu) responds to each of his parishioner’s moral entreaties with a rapid-fire citation of a bible verse. It’s a bit like listening to Ben Shapiro debate a college student, because the more closely you listen, the less relevant his responses seem to be.

In addition to all of the above, Kontinental ’25 is a pleasure to look at. DP Marius Panduru (who shot Jude’s 2015 film Aferim!) employs crisp wide-angle cinematography that emphasizes the contrast between Cluj’s classical architecture and the hard primary colors of nascent capitalism. As with Jude’s other recent films, the landscape is of paramount importance here, and not just because a real estate deal is the precipitating cause of Orsolya’s dilemma. Kontinental ’25 subtly explores what philosopher Henri Lefebvre called “the right to the city,” the ways in which simply moving through space becomes a privilege afforded only to a select few when the category of “citizen” is replaced with that of “landowner.”

At this point, Radu Jude is working at the height of his artistic powers. In his analytic approach to the depiction of capitalism’s distorted realities, he provides a link between the present moment and the works of Godard’s 1966-69 hot streak: from Masculin Feminin to Le Gai Savoir. Compared with Jude’s last few films, Kontinental ’25 is a bit more accessible, with a clearer focus and a compelling (if compromised) central character. This film should be a breakthrough hit, although living as we do under the strange vicissitudes of late-late-capitalism, who’s to say? — MICHAEL SICINSKI

Fuck the Polis

So many of the dialogues between mortals and immortals in Cesare Pavese’s Dialogues with Leucò end with the gods in agreement that the divines share more in common with the beasts than with mortals. Both wolves and gods concern themselves with only an eternal present, but humans, always aware of their own death, are beings forged by the dual anxieties of a wasted past and an ever-shrinking future. When travelers turn to Greece looking for the birthplace of Western culture, they anticipate the temples of the divine whose relationship with mortals gave us fire and art and politics, but they forget that this culture was equally shaped by the bulls and beasts whose figures also emblazon the walls of these same temples. Alan Bates’s Basil learns of this in Zorba the Greek; Byron learned of it during his participation in the Greek Revolution of 1821; and even Odysseus was, for a time, but a traveler in these lands full of gods and monsters. Our relationship with beasts and the divine helped build the polis, but its fruits, what we call “civilization,” also made us more aware of the one element that differentiates us from both. Little wonder Socrates spoke of philosophy as “learning how to die.”

Rita Azevedo Gomes’s latest film, Fuck the Polis, meditates on such Mediterranean travel and death. Her own voice narrates the story of the Portuguese Irma’s journey throughout Greece’s Cyclades. The year is 2007, and a mysterious diagnosis has encouraged this traveler to board the tourist ships by herself as she visits the scattered ruins of Mykonos and Delos. Along the way, she meets a local named Ion who flirts with her as they travel through the mostly empty islands. Perhaps the zephyrs of these Homeric lands have inspired the two, as they speak to each other almost exclusively in poetic observations. Ion is compared to his mythological namesake (the bastard son of Apollo and the namesake of the Ionian people; though the unrelated Ion, a Greek man who challenged Socrates on the role of poetic inspiration, of Plato’s Ion is perhaps a better comparison), and Irma observes that they’re connected by the initial iota of their names. Irma hugs the ancient statues in Delos’s museum and absorbs their warmth and speaks of appeasing the divine and speaks of the color white, its omnipresence among the buildings dotting the Cycladic landscapes and the clouds above, representing death.

But we see none of this. Or do we? The Irma of the narration both is and isn’t Rita Azevedo Gomes — she reads from a story by João Miguel Fernandes Jorge called “A Portuguesa,” which is a fictional recounting of Gomes’s own 2007 trip to Greece. Fuck the Polis switches between representations of this past trip, evoked by sudden switches to Super 8 and SD video, and the “real” trip of present day where Gomes and her coterie of bardic youngins read texts about Greece to each other as they repeat much of the same journey. The result is a film that uses poetry and prose to blend pasts (recent and ancient) and presents (fact and fiction). The one constant is the sea, Homer’s very own wine-dark, that here subjects itself to portraiture in every format. Then, suddenly, another narrative arises as the group ventures to the home of Greek singer Maria Farantouri whose contralto had once let Gomes know that she had arrived in this mythical land.

As much as the film purports to be about these little odysseys, most of the film’s images are simple beautiful landscapes. Shots of the ship arriving in port or of the wind winding through the grain fields hold so that the landscape may come into better focus. Or the opposite: SD video shots of red kylix-shaped flowers give way to the video’s aliasing, resulting in an impressionistic sea of crimson with no discernible lines. Sometimes these images work like a child’s picture book, giving us literal imagery to accompany the story being told, such as showing a statue when Irma hugs the statue. Others are not so literal, like an extended overhead shot of cars and travelers marching haphazardly onto the ship while a piano plays staccato, as if remaking Workers Leaving the Factory for a mere interlude in the story. Befitting the collective nature of the trip, the cinematography is credited to Gomes herself as well as two of the actors, Bingham Bryant and Maria Novo. At times, it can feel like one has simply been roped into viewing someone’s vacation footage where landmarks made familiar to one’s eyes through Google searches are made only slightly more interesting by the inclusion of recognize people. But most of these images are punctuated by moments of strangeness: the Thanatotic humor of goat skulls arranged before the goats, tourists in their telltale garb traipsing about holy ground, or Maria Farantouri herself singing along to her 2007 broadcast.

Hidden within the two travelogues is a third narrative: a small poetry exchange between Bingham Bryant and Loukianos Moshonas. They both read excerpts from poems that reflect on the outsider’s view of Greece (Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage and Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” among others) without context; it may be a battle of verse or an attempt to put these poems in conversation with each other. Regardless, these scenes mark Gomes’ awareness that the inspiration for her travels is nothing new and that she’s following the voyages of many other artists as much as she follows her own 2007 trip. Fuck the Polis, its incendiary title lambasting the notion of Greece’s “rational” civilization, works best when it revives these stories of travel and tragedy and ties them together with her own. When they finally reach Maria Farantouri, their own Oracle of Delphi, she clarifies part of her song: “Where there is death, let’s make love there.” — ZACH LEWIS

Next Life

A father dies, the family prepares the deceased for the next life. The simplicity of the premise of Tenzin Phuntsog’s narrative feature debut, Next Life, at once justifies its austere tone and atmosphere and belies its complex and sensuous spirituality. The dialectical nature of Phuntsog’s point of view allows contradictions and ironies to take precedence over character development and narrative logic, and suggest a bridge between life and death that is, perhaps, not one-way.

The first image we see in Next Life is of a collection of items in a small nook in a suburban Northern California home: family photos, a portrait of the Dalai Lama, and a carved skull statue. Religion, just like American prosperity, is leaden with symbolism; in Buddhism the skull encourages detachment from the physical self, reminds practitioners of mortality and impermanence, represents the destruction of ego. The scene that follows is indicative, then, of Phuntsog’s preoccupation with contradictions. Pala (Tsewang Migyur Khangsar) has fallen ill; vague pains in his heart that spread throughout his body, dreams of his childhood in Tibet. His wife Amala (Tseyki Dolma) and son Rigzin (Rigzin Phurpatsang) sit in the background, blurred and detached, while a Tibetan doctor listens to the heavy, earthen thuds of Pala’s pulse, and provides a solemn reading: he doesn’t have long to live.

Depending on your own sensitivity to contradiction and irony, close attention to the body is either in harmony with spiritual transcendence or in conflict with it. So, too, does a conspicuous emphasis on technology in Next Life both facilitate emotional and spiritual connections to the family’s homeland and draw attention to their physical isolation. With subject matter as ritualistic as Buddhism at its center, seeing karaoke night represented as crucial a tie to one’s homeland as prayer, or a VR headset (literally and symbolically perched on the wearer’s skull) as providing the same healing respite from the world as a real walk in nature, is profoundly complicated.

Aspects of Pala, Amala, and Rigzin’s isolation are, indeed, involuntary. Who can blame Pala, an American citizen, for admitting that he’s never felt like an American? Rigzin’s efforts, in English and Chinese, to secure his father a visa to travel to Tibet are unsuccessful; his calls to the Chinese Consulate are rarely put through to a human being in the first place, a cruel, impersonal layer between one life and another. One also wonders how welcoming the surrounding neighborhood has been to his family. The viewer will never know; any trace of life within the immaculate rows of manicured lawns and cookie cutter homes is gone, but for a smattering of SUVs clinging to sloped driveways, these lumbering symbols of prosperity pointed upwards to even bigger ones.

At the doctor’s request, Pala and his family spend time in nature. A lone tree perched on a grassy hill becomes a place of peaceful refuge and reflection, as does a small patch of woodland where at any moment it seems as if someone could walk behind a tree and never reappear. Rigzin cares for his father in his dying days and mourns him in the days after. Gentle baths, cooked meals, calls to the consulate and distant relatives, and a private conversation between the living and the dead all take on literal significance.

Maybe the tears he sheds on the hillside mean some ego is necessary after death, lest the grief gnaw away at you from within. He meets with a Lama who explains the four stages of life on earth, each one more painful than the last. Rigzin doesn’t experience a religious breakthrough, but perhaps he’s not in need of one. He’s searching, in some way – when he dons the VR headset like his father did before and wanders around the meadow on the Tibetan mountainside – searching for whatever it is his father remembered, and perhaps now sees again. — CHRIS CASSINGHAM

Measures for a Funeral

“The decade-long collaboration between Sofia Bohdanowicz and Deragh Campbell has produced a fascinating cycle of films, including features and shorts, that goes some way in shaping a quasi-personal archive of Bohdanowicz’s life and family history. Most of the films stage encounters between Campbell’s recurring character, Audrey Benac, a Bohdanowicz alter-ego, with art, history, and archives in order to trace emotionally resonant links between the past and the present. Sometimes Bohdanowicz’s own family members appear in the films, extending her self-reflexive tendencies even further…” [Previously Published Full Review.] — CHRIS CASSINGHAM

Conference of the Birds

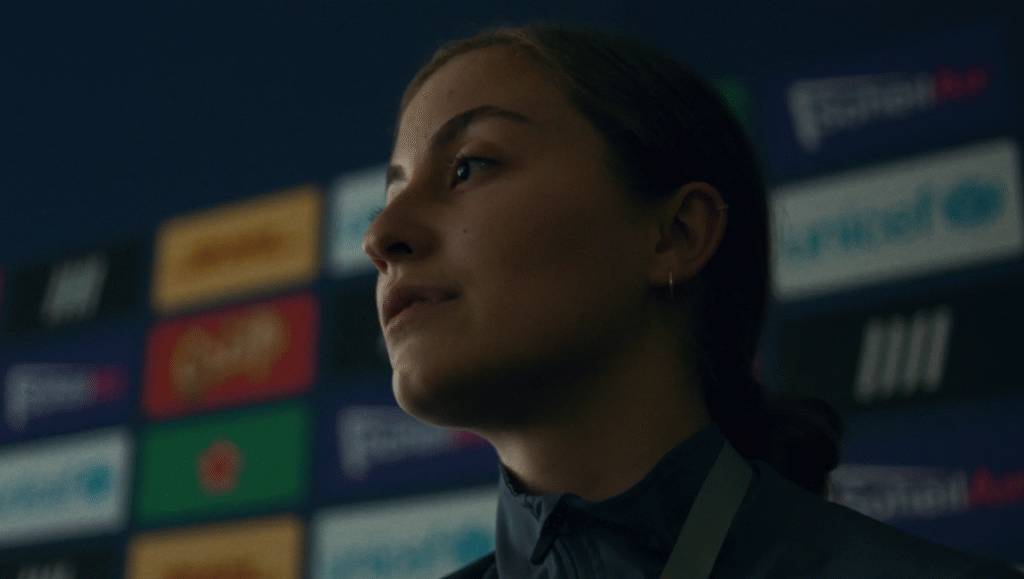

In his first feature Conference of the Birds, director Amin Motallebzadeh borrows a title from a revered source: 12th-century Sufi poet Farid al-Din Attar’s allegorical poem The Conference of the Birds, in which a horde of birds embark on a quest to find the mythic Simorgh to serve as their leader, yet come to the ultimate discovery that they already contain the mystical bird within themselves. The purpose of this reference is clear in the basic narrative conceit of Motallebzadeh’s film, in which a prominent football club struggles to find a path forward after the sudden death of their coach. Dispensing with anything resembling a conventional three-act structure, Motallebzadeh films the discombobulated members of the club in isolated, cryptic moments as they process their unsettled present and uncertain future. Unlike the avian pilgrims of Attar’s poem, the characters populating Motallebzadeh’s film have no quest to pursue, and they cannot even make sense of their present reality.

Motallebzadeh noted that the film was not built around a pre-determined narrative, but instead was built around a collaborative process and, sometimes, was influenced by external circumstances: “… we made the film—not from a fixed idea or plot, but rather backwards, by responding to what came up during the process. For instance, the coach’s death only came up after we lost the actor we had cast. Looking back at the footage we had shot so far, that absence made sense—it was already there.” This semi-improvisatory, patchwork approach is evident in the film’s presentation. The film consists of a series of immaculately staged events—some idiosyncratic group activities, some more solitary happenings—that occupy an uncertain space between the mundane and utterly strange. These include a press conference where the interim coach, through a translator, responds to a question about the coach’s death by dejectedly stating “I only know what I don’t understand,” a team training exercise shot to appear like a vigorously athletic and precisely choreographed dance, and an interminable verbal reading of a player’s contract.

Motallebzadeh does not stitch these scenes together with obvious narrative threads, and generally does not even give his characters names, instead allowing the audience to make connections between characters and events as they slowly unfurl. The cast acts in a uniformly somnolent style, speaking slowly and pausing frequently, with minimal facial expressions and vocal inflections. This style distances the viewer from the actors, and instead draws attention to their physical movements — particularly in a number of scenes featuring repetitive motions, including Muslim prayer and stretching exercises — and their often-cryptic, sparse dialogue, which is sometimes repeated by different characters in different contexts.

As Motzabellah has described, the “film moves in circles rather than lines.” With its spartan aesthetic and repetitious, diffuse narrative, Conference of the Birds can alternately be difficult to parse and mysteriously absorbing. A cumulative effect of spiritual isolation builds over its duration — notably, religion is a motif in the film, with several of the characters being practicing Muslims — that stands in ironic contrast to the collective nature of a team sport. In this respect, Conference of the Birds is an impressive subversion of how sports are usually portrayed on film, with a team coming together to prepare for a big game that ends in an inspiring win. This film does build to a climactic game, but for enigmatic reasons, the team doesn’t even show up. Their interim coach had previously advised them to act like “shadows” to gain an advantage over their competition, doling out the advice to “play like you don’t exist.” This message, of course, carries existential implications beyond the playing of a game of football, and is paralleled in the elusiveness of the film itself. Before Conference of the Birds can be fully grasped, the film slips away, leaving one as unmoored as its searching characters. — ROBERT STINNER

Revelations of Divine Love

Julian of Norwich was a religious mystic and anchoress in the Middle Ages. After a grave illness during which she experienced visions of Christ on the cross, Julian lived out her days in a cell at the St. Julian’s Church, where she received visitors and pilgrims, as well as writing a spiritual text that detailed her Christianity and divinely inspired hallucinations. The book, Revelations of Divine Love, is the earliest surviving text in the English language to have been written by a woman.

Many feminist theologians over the years have turned to Julian’s text in order to get an all-too-rare picture of the life of an otherwise ordinary woman in the Middle Ages. In her remarkable new film, Caroline Golum stages the life and visions of Julian (Tessa Strain), depicting her life as an anchoress. With its slow pace and the deliberate diction of her performers, Golum has produced a film of classical rigor and a not inconsiderable didactic impulse. In visual style, Revelations echoes the Brechtian approach of Manoel de Oliveira, with his clear signifiers of the period coexisting with a haunted, atmospheric modernity. But probably the most apposite points of comparison are the late educational films of Roberto Rossellini. In works like The Age of the Medici (1972) and Cartesius (1974), Rossellini created a space on Italian television for an examination of history and discourse. And like Golum’s film, the Rossellini works demonstrate the styles and mores of the period, rather than attempting to convince the viewer of their cinematic reality.

Julian’s illness and initial visions can be seen as a sort of prologue, wherein the young woman is seen in the context of her home and family – in particular the domestic activity of her mother (Mary Jo Mecca), sisters, and cousin/servant/best friend Sarah (Isabel Pask). Against this bounded feminine life, Julian’s visions are lush, sensual, and violent. As has been the case through the centuries, “madness” affords a woman the freedom of bold, untethered experiences, permitting a kind of travel of the mind. The irony of Julian’s situation has not been lost on critics and commentators over the years. By allowing herself to be permanently walled into the single room of the church, Julian takes the only available avenue for departing the domestic sphere and having social engagement, however limited.

Being an anchoress also permits Julian to be a writer. We only know of her existence because of the surviving text, and Golum depicts the thoughtful if demure Julian as a conscientious thinker and observer of the world around her. Her meditative pursuits are supported by her confessor, Father Ambrose (Theodore Bouloukos), with a compassionate paternal care. However, this is the time of the Black Plague, and while Julian’s anchorage keeps her protected from the disease for quite some time, it also renders her a passive spectator to the horrors of her era. Revelations depicts the anguish that Julian feels regarding the life she witnesses beyond her four walls.

Various townspeople come to her window to seek her counsel. One young woman confesses to Julian that she has committed the sin of envy, because she wishes she had died of the plague along with her children. Another young man describes rampant labor exploitation in his village and, in precisely coded language, informs him that God permits the oppressed to overthrow their oppressors, even violently if necessary. While Golum doesn’t suggest that Julian was the first liberation theologian, her film demonstrates that many problems of our time, as well as the possible solutions, have haunted society from its earliest days. And despite the structural marginalization of women, their desire for a full life has also been a constant, and is not (as some contemporary conservatives would have it) a cultural invention borne from feminism itself.

Throughout the film, Golum returns us to an establishing shot of St. Julian’s Church and the candlelit window where the anchoress resides. This shot does not mean to convince us of its verisimilitude; it is quite clearly a miniature model. (Art director Grant Stoops deserves particular mention for the meticulously crafted look of the film.) But this is part of Golum’s unique cinematic style. In its patient manner, this film means to show us a model of a “small life,” one confined to a six-by-six room which she would only exit upon death. (The film implies that Julian may have been permitted to leave by the Church, an option she spurned.) Throughout the film, the simple, solid-colored clothing and roughly thatched rooves openly display the modesty of Golum’s production. But at various points, Julian’s world is saturated with holy light. Golum and DP Gabe Elder bathe Strain and her surroundings in a glow worthy of Vermeer or Rembrandt. The message seems clear. There is no necessary correlation between an individual’s material circumstances and the power of their illumination. — MICHAEL SICINSKI

Requiem

Anyone who has made as many masterpieces as the French experimental director Jean-Claude Rousseau deserves his occasional oddities and indulgences, but his new 10-minute short Requiem isn’t going to be what convinces novices of Jean-Marie Straub’s usually justified claim that he is one of Europe’s finest filmmakers. It’s best not to use it for a judgement call as to whether to watch more of his work. The film’s description deserves credit for easily summarizing the entire film: “As the orchestra choir settles into the church choir, the trombonist blows into his instrument as a warm-up. Mozart’s name appears at the top of the score to be performed, whose title is also that of the film: Requiem.” We get the opening shot of the trombone player blowing his instrument, a fade to black that covers the opening of the piece before he enters, and then the image resumes when he begins his contributions to the performance. The unbroken second shot covers the remainder of the film until the piece is finished and the applause begins, taking us to the credits. Rousseau shoots all this from directly behind the trombone player, in a cramped composition mostly emphasizing the back of his head and clearly shot quixotically on his smartphone. While it’s something of a noble gesture to emphasize the trombone player’s contributions to the performance, and it’s hard to object to getting to hear a lovely performance of the Requiem from an unusual perspective, this ultimately isn’t much of a movie. (Smartphones mean the raw rushes of shooting get used as unadorned pieces of art in their own right more than ever before.) It lacks the recontextualization and variation that marks the best of single-take movies, and is probably going to ultimately serve as little more than a footnote or a curio in the Rousseau oeuvre. — ANDREW REICHEL

Comments are closed.